Q&A: What We Know (And Don’t) About Homo Naledi

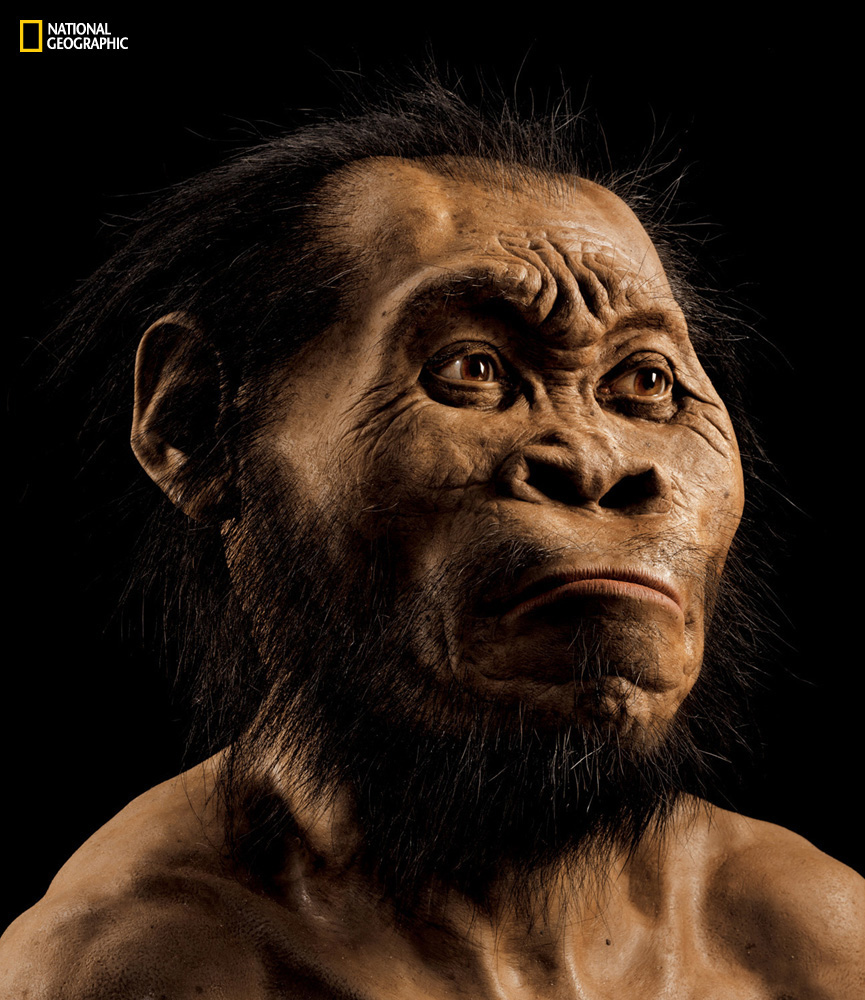

A reconstruction of Homo naledi’s head by paleoartist John Gurche, who spent some 700 hours recreating the head from bone scans. The find was announced by the University of the Witwatersrand, the National Geographic Society and the South African National Research Foundation and published in the journal eLife.

Any discovery of early fossils unlocks important pieces of our evolutionary puzzle.

But the excavation of a new human-like species, Homo naledi,from deep within a South African cave defied all expectations: Scientists discovered 1,500 bones – the skeletons of at least 15 bodies.

There are, however, plenty of questions that remain. Along with our show on the discovery of Homo naledi, scientists at the University of the Witwatersrand, National Geographic Society and eLife talked about what they know – and what they don’t – in this Q&A.

Question: How do you know that this is a new species?

Answer: The unusual combination of characters that we see in the Homo naledi skulls and skeletons is unlike anything that we have seen in any other early hominin species. It shares some features with australopiths (like Sediba, Lucy, Mrs Ples and the Taung Child), some features with Homo (the genus that includes Humans, Neanderthals and some other extinct species such as erectus), and shows some features that are unique to it, thus it represents something entirely new to science.

Q: How do you know it belongs in the genus Homo?

A: The brain of H. naledi is small; similar to what we see in australopiths, but the shape of the skull is most similar to specimens of Homo. For instance, it has distinct brow ridges, weak postorbital constriction (narrowing of the cranium behind the orbits), widely spaced temporal lines (attachments for chewing muscles), and a gracile set of jaws with small teeth, alongside a whole host of other anatomical details that make it appear most similar to specimens of Homo. Also, the legs, feet and hands have several features that are similar to Homo.

Q: Where does H. naledi fit within the human lineage?

A: This is a more difficult question, since our understanding of the human lineage has changed in recent years owing to a large number of new fossil discoveries like sediba and Ardipithecus ramidus. However, given that H. naledi shares some characters with australopiths, and other characters with species of early Homo such as H. habilis and H. erectus, it is possible that this new species may be rooted in the initial origin and diversification of the genus Homo. At the same time, H. naledi shares characters that are otherwise encountered only in H. sapiens. As a result, our team has proposed the testable hypothesis that the common ancestor of H. naledi, H. erectus, and H. sapiens shared humanlike manipulable capabilities and terrestrial bipedality, with hands and feet like H. naledi, an australopith-like pelvis and the H. erectus-like aspects of cranial morphology that are found in H. naledi. Future fossil discoveries in the Dinaledi Chamber and elsewhere will certainly help us to test this hypothesis.

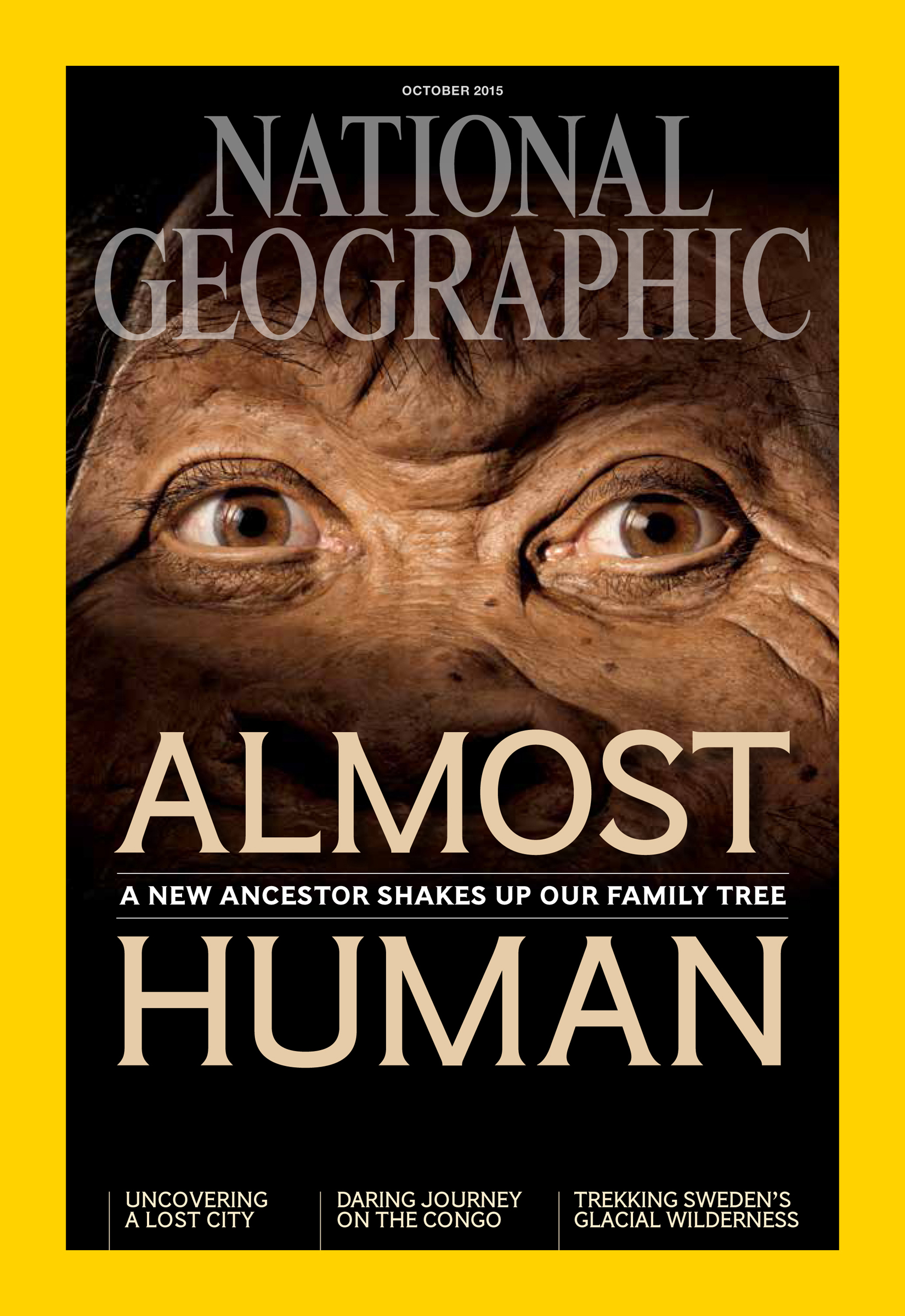

Paleoartist John Gurche used fossils from a South African cave to reconstruct the face of Homo naledi, the newest addition to the genus Homo.

Q: Why is the combination of features in H. naledi unusual or unexpected?

A: Until recently, most anthropologists believed that brain size and tool use emerged together with smaller tooth size, higher-quality diet, larger body size and long legs. In this view, transformations in the body in early Homo were tied to changes in behavior that influenced diet and the brain. H. naledi shows that these relationships are not what anthropologists expected. It has small teeth and hands that seem to have been effective for toolmaking but also a small brain. It has long legs and human-like feet but also a shoulder and fingers that seem effective for climbing. The features that were supposed to go together are not found together in H. naledi, and that creates an interesting puzzle that will force us to review our present models of the origins of our genus.

Q: Why is it so hard to date the fossils?

A: Unlike other cave deposits in the Cradle the fossils are not found in direct association with fossils from other animals making it impossible to provide a faunal age. There are also few flowstones that can be directly linked to the fossils, and those that exist are contaminated with clays making them hard to date. On top of that, the fossils are contained in soft sediments and they are partly reworked and redeposited making it difficult to establish their primary stratigraphic position. Taken together, this makes it hard to obtain a definitive date for the fossils.

Q: How were the fossils found?

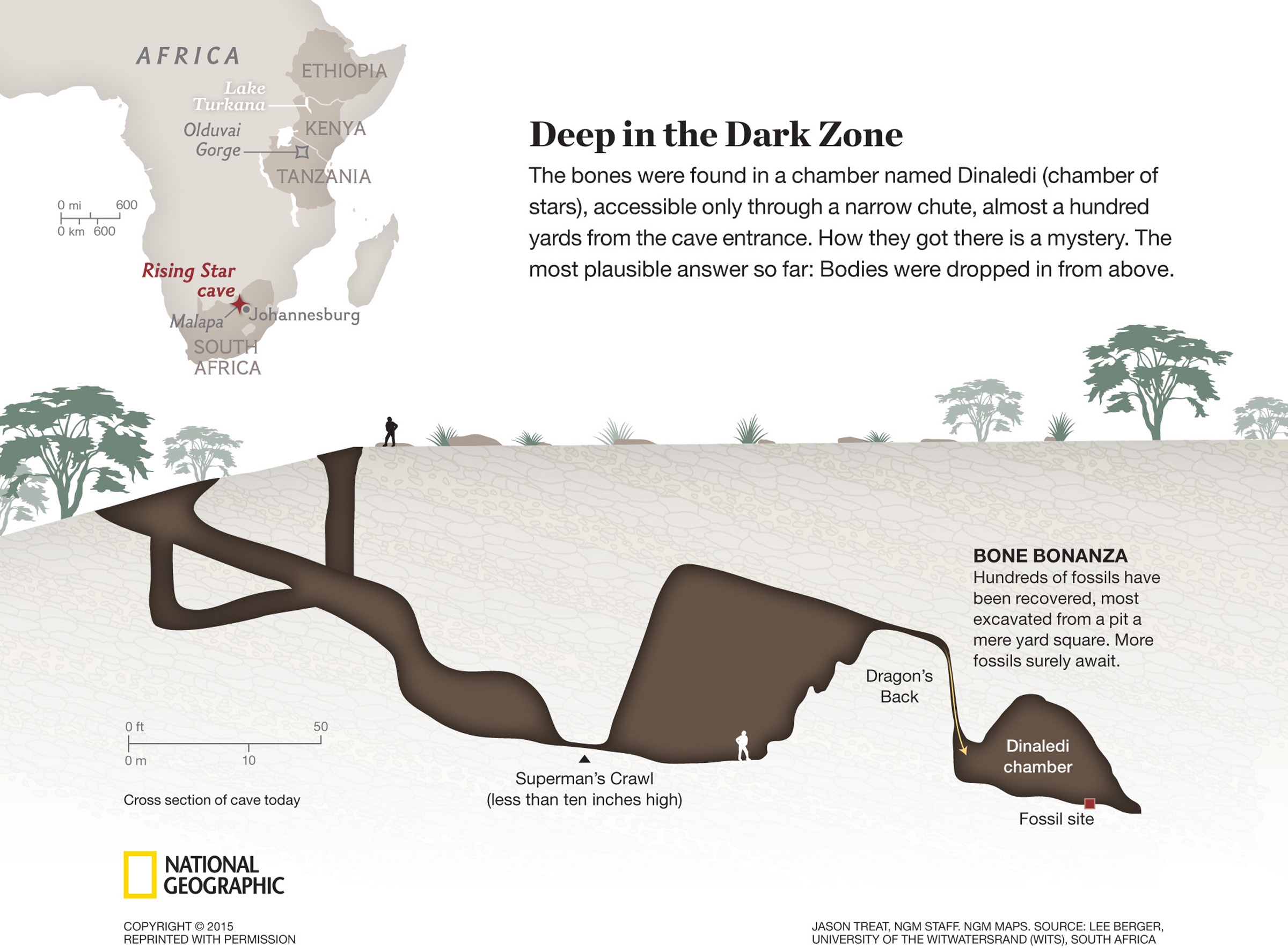

A: Two cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, when probing a narrow fracture system to the back of the cave system found the entrance into the Dinaledi Chamber and discovered the fossils. When they showed pictures of the fossils to Pedro Boshoff another caver and geologist, he recognised the fossils as potentially significant and alerted Professor Lee Berger to the find. Further detailed investigations followed, which quickly demonstrated the significance of the find.

A cross-section showing the Dinaledi chamber within the Rising Star cave near Johannesburg, South Africa, where the fossils of a new species, Homo naledi, were discovered. A team of six “underground astronauts” navigated the extremely narrow chutes to recover more than 1,500 fossil elements discovered in the cave. The find was announced by the University of the Witwatersrand, the National Geographic Society and the South African National Research Foundation and published in the journal eLife.

Q: How many Hominin fossils are there in the Dinaledi Chamber?

A: We don’t know. So far we have recovered 1550 separate bones and bone fragments from the floor surface of the cave chamber, and from a one small excavation near a bone concentration in the back of the chamber. Based on duplicate bone elements it can be shown that these bones belong to at least 15 separate individuals. Shallow probes in other parts of the Dinaledi Chamber suggest that there are bones across the chamber floor and we therefore expect to find many more bones from many more individuals as excavations continue.

Q: Why is the Homo naledi foot so important?

A: It’s important for two reasons. Firstly H. naledi is a brand new species of fossil hominin, and its foot is a crucial part of the discovery as it tells us something about how it moved around. Second, walking upright is one of the defining features of the human lineage, and as feet are the only structure that make contact with the ground in bipeds, they can tell us a lot about our ancestors’ way of moving.

Q: Did Homo naledi walk like we do?

A: Mainly, but not exactly. This is for two reasons. Firstly, although very like our own, the H. naledi foot does have a few features that are not entirely human-like. Its toes would have been slightly more curved and it may have had a lower arch than the average human. The second reason is that the way a creature moves does not just depend on its foot. One has to look at the rest of the skeleton as well. When we look at the whole skeleton of H. naledi, we see a creature that walked upright, but was also comfortable climbing in the trees a little bit.

Q: Why is the H. naledi hand skeleton an important find?

A: This fossil human hand is important for several reasons, but especially because it is so complete. There are 27 bones in each human hand and this fossil hand preserves all of the bones of the right hand, except for one wrist bone called the pisiform. These bones were found partially articulated (i.e., joined together)—an extremely rare event in the hominin fossil record—meaning that they belonged to one individual. Within this single hand, there is a mix of features that has never been seen before in any other hominin species. The wrist bones, particularly those on the thumb-side of the hand, show several adaptive features for tool-related behaviors that are consistently found only in modern humans and Neandertals whereas the finger bones are more curved than most australopiths. Thus, this one hand suggests that even after the hominin hand had become well-adapted for complex manipulation, some hominins were still spending large amounts of their time climbing.

Q: What are the implications of the H. naledi hand for human evolution?

A: One of the most contentious debates in human evolution is whether early hominins spent significant amounts of time climbing or were strictly walking on two feet on the ground all the time. H. naledi sheds important new light on this debate. The presence of such strongly curved fingers (rather than the straight fingers of humans/Neandertals) suggests that its fingers were curved for a reason: H. naledi regularly used its hands for climbing. Furthermore, depending on how old (geologically) the H. naledi remains turn out to be, there will be important implications for interpreting the South African archaeological record, who made the various stone tools that have been found, and what anatomical adaptations were necessary to craft these implements.

Want to hear more about Homo Naledi? Listen to our full hour.