Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

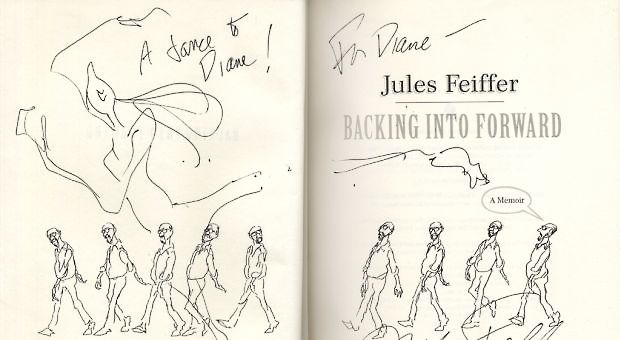

Cartoonist, playwright and author Jules Feiffer tells us how he went from a self-described wimpy kid from the Bronx to one of the 20th century’s most famous voices of satire and dissent.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. Cartoonist and writer Jules Feiffer has been called the bridge from Lenny Bruce to "The Simpsons." In a new memoir, the award-winning humorist talks about a six-decade career that has taken him beyond drawing cartoons to acclaim as a playwright and author. His new book is titled, "Backing Into Forward." And Jules Feiffer joins me in the studio. Rave reviews coming out about his book, and I know there are many of you who've appreciated his work over the years. Give us a call, 800-433-8850. Send us your e-mail to drshow@wamu.org. You can join us on Facebook and Twitter. And do check out our new website at wamu.orgdrshow (sic) -- no, it's drshow.org. That's what it is. Got it. Jules Feiffer, how lovely to see you.

MR. JULES FEIFFERLovely to see you again.

REHMYou are looking quite well. You must be very happy to have completed this book.

FEIFFERAnd why not?

REHMWhy not, indeed.

FEIFFERThere must be a downside to all of this, but I can't figure out what it is.

REHMHow long did you work on this book?

FEIFFERWell, it was about five years altogether because after the first year or so of working on it -- sometimes haltingly -- my wife, Jenny, came down with cancer. And somehow, rather, that doesn't compel you to want to write a memoir, so I stopped for about a year, a year-and-a-half. And she got through that and got through it wonderfully, and then I resumed work. And that layoff seemed to do me some good. It gave me a greater sense of direction and stronger motivation. I began enjoying myself. I began to actually think I knew what I was doing, and that led me to move along. And when I started, I thought there's no way of doing this because I don't remember anything. And it's a funny thing about memory. As you write down one thing, suddenly other things start popping up that you hadn't thought about in many years, and I'd make notes.

REHMIsn't that wonderful?

FEIFFERIt is wonderful. It is wonderful and spooky.

REHMSpooky?

FEIFFERYes.

REHMBecause these memories keep popping up?

FEIFFEROh, well, because these -- you know, because you don't know who this person is inside your head, who somehow has a very selective sense of what is really going on, you know, that the storage bin that I've walked around with -- sometimes it's accessible, and sometimes it isn't.

REHMYou know, I'm looking at the cover of this coming Sunday's New York Times book review, which has your drawing on the front, and it says, "The end. The book is over. Now you know everything." Now, Jules Feiffer, are you telling me truthfully that everything that we know is everything that you have known?

FEIFFEROh, nothing is everything -- and not even I know what I'm saying there -- but it's a cartoon.

REHMIt's a cartoon.

FEIFFERAnd cartoons are meant to -- oh, I don't know -- either be misleading or symbolic or a metaphor. So it's all of the above.

REHMYou talk a great deal in the book about your bringing up your ambitions. Talk about your childhood.

FEIFFERYes. Well, as a kid, as I say in the book, I lived in the Bronx. It was during the years of the Great Depression. Everybody on the street was poor, and so nobody really made a big deal about that. We were all in the same boat, and everybody -- every kid on the street -- was an athlete, except this boy. I couldn't throw a ball. I couldn't catch a ball. I -- well, I had none -- I had, not then or now, an athletic bone in my body. So in order to achieve some kind of position where I was safe from being bullied or beaten up or pushed around by the other kids, you have to establish some turf, some area of respect. And I knew I could draw, and they couldn't. So I'd go out to the sidewalk with a stick of chalk. And while they were playing ball, I'd just start drawing, pretending that I didn't pay attention to them, until they started paying attention to me because I was drawing Popeye. And I was drawing cowboys from the movies. And I was -- yeah -- and they couldn't do that. So I got some respect, and they left me alone.

REHMThey left you alone. And did you, at any point, yearn to have the kind of athletic ability that they had?

FEIFFEROh, well of -- the fantasy. And all -- I don't know how many cartoonists over your long career you've run into -- of course, this microphone -- but we are a very weird group.

FEIFFERWe are not like anyone else. And when we are together, we all appreciate each other. There's a -- I have a friend, a good friend named Irwin Hasen, who's in his 90s, and he did "Dondi" for many, many years. And he's in wonderful health after having a serious stroke a few years ago. He's terrific again. And we get together for a drink, and he looks at me, eyes twinkling, and he says, I can't believe I got away with it. And I always say to him, Irwin, every one of us feels that way.

REHMHow about your parents? Did they appreciate your talent?

FEIFFERWell, my mother was a fashion designer. And she got us through The Depression. My father opened and closed men's shops within 15 minutes. You know, he'd open a store on a Monday and we'd close on a -- by Monday afternoon. And so my mother made the living by basically peddling designs down on 7th Avenue Manhattan Garment Center, going door to door and selling her stuff. So she drew. And she encouraged my drawing, and she encouraged cartooning. Cartooning back in the '30s and '40s had a degree of glamour to it that it had subsequently lost. I mean, that cartoonists would -- hung out with show business people, and they did -- they went into Vaudeville and the Sunday supplements with huge, glorious sections, which ran lots and lots of pictures and beautifully done.

FEIFFERI have a sizeable collection at home in my library, and I still look at the stuff in glory over it. And as a kid, I gloried over it even more. And as a children's book author and illustrator now, what I do when I start illustrating a new book -- either by me or someone else -- I go back to my old files and go back and look at that work that I loved as a kid and draw inspiration for what I'm going to illustrate from the work I loved at seven.

REHMWhat about your teachers? How did they feel about your cartooning?

FEIFFERWell, when you teach -- when you're in school, you're supposed to be listening to what the teacher says. And I daydreamed, and I was known as a daydreamer. And if I wasn't drawing in the margins, I was looking at the window. I was doing almost anything but paying attention. And so my success in school was intermittent. I got through by -- I don't how I got through. I wasn't paying attention, and I slicked my way through. I mean, I lied, cheated and stole. I mean, I just did whatever I had to do to pass the test and, you know, writing on your fingernails -- the answers on the cuffs and just to get out of there. I knew that I had to get out of school before I could start a life.

REHMYou did not have any ambition to go to college?

FEIFFEROh, I had an early ambition to go to college until NYU School of the Arts turned me down and -- it was the Cooper Union, yes. I took their admissions test. They said I couldn't draw. So after that, I thought, well, this isn't going to work and went out and started my career to the extent I could. And, I mean, I understood that college was only a weigh station anyhow because I was out to become a famous cartoonist. And why should I wait another four years?

REHMYou really had in your mind, I will become a famous cartoonist?

FEIFFERYes. Now, what that meant, I had no idea. I meant to be in the tradition of Al Capp, who did Li'l Abner, or Walt Kelly who was doing Pogo. I wanted to do something satiric, a daily strip. I didn't know what it would be about. I didn't know what direction, and I wanted the humor to be gentle and ironic. I had no idea I was going to end up doing the kind of angry, political satire...

REHMHmm.

FEIFFER...that I ended up doing.

REHMHmm.

FEIFFERThat was shaped by the United States Army a few years later when I was drafted. But I wanted a rather conventional career. And if I had some early success -- which I didn't -- at doing this work, I would have had a very different life, a very different direction. For that matter, early on, when I was trying to do conventional comic books, if I had any success at that, I would have been a very happy hack.

REHMHmm.

FEIFFERI mean, I stumbled into quality. It wasn't anything I was looking for.

REHMBut picking upon what you've just said, it was really in the Army, was it not, that you began to blossom?

FEIFFERYes. The -- well, blossom in the Army is a strange -- maybe an oxymoron.

REHMBut that's when it really came together?

FEIFFERWell, it's where -- earlier in my life, in my Bronx life, whether I was coming up against parents or teachers or other forms of authority, the authority posed -- sometimes justly, sometimes not -- as benign. They were out to do you good. They were out to help you. They were out for the best. So the degree of anger one had, or I had, was buried -- was suffused in other directions because, after all, these people mean well even though I don't feel that they're doing me well. In the Army, they didn't mean well. In the Army, they were out to destroy me in order to rebuild me as a soldier.

FEIFFERThey destroy one's individuality, destroy one's sense of self, and the whole thing was to make you part of a cohesive unit so that no one thinks for himself any longer -- that's the way it was back then. I don't know what it is now -- but thinks as if you're part of the platoon and part of the company and part of this. And that's what they say they're going to groom you for. Now, there are millions of young men who take this information with mock seriousness and just do what they have to do and get through it. With me, it just destroyed me, and I basically fell apart. And while falling apart, I had to figure out some way of rescuing myself, and that's where satire came in.

REHMJules Feiffer, his brand-new memoir is titled, "Backing into Forward." Short break, right back.

REHMMy favorite cartoonist in the world is here with me. His name is Jules Feiffer, and he's written a memoir of six decades in his career. The book is titled, "Backing Into Forward." We do have a few of his cartoons up on our website regarding Superman, and you can go to drshow.org to see them. But right now, Jules Feiffer, I want to ask you to read a portion that concerns a dog you had, a dog you loved. And I have to tell you, I read that and had a really, really hard time experiencing what you experienced. So, please, read for us.

FEIFFERWell, this followed my mother calling me up many years after this incident and asking me on the phone. She must have been in her mid-60s, and she said, sonny -- which was her code name for me -- I read these articles and magazines about these successful men who resent their mothers or hate their mothers, and I just wondered if there's anything you resent me for. And I lied, of course, and said, no, ma. But then I go on to write, "Should I mention Rex, the beagle pup given to me when I was seven? Rex, who was my friend in a friendless world, who sat in my lap with me, cross-legged on the floor, worshipfully gazing up at the old Philco console as it played my favorite radio serials. Rex, who followed me, jumped all over me, licked my hands and face. Rex, who, when I came home from school one day in early spring and looked for his leash in the kitchen closet and didn't find it and called his name, 'Rex, Rex,' repeatedly. And Rex was nowhere in sight.

FEIFFERI found my mother bent over her drawing table, in the far corner of our living room, behind the piano no one knew how to play. I asked her where Rex was, and this is what my mother told me in this Jewish mother joke. I can't talk. Can't you see I'm busy? But I insisted. Just tell me where Rex is. Most of my young life, I didn't have the nerve to insist to my mother. I was no match for her. She could outtalk, outthink and intimidate while at one and the same time manage to make me pity her for how much she had sacrificed and how little she was thanked for it. I was putty in her hands, but not at this precise moment. I wanted to know where my dog had gone, and I knew she was holding out on me.

FEIFFERFinally, after much prodding, she came out with the truth. My mother had given Rex away to a farmer who had a little girl, who would give Rex a good home in the country, better than the cramped apartment in the city. And she hadn't told me at first because she knew I'd go and make a scene. And with all that she had to do -- cook, clean, make a living to see us through the Depression -- with all these responsibilities, she couldn't take on the extra responsibility of a dog. I had no way of absorbing and/or making sense of her revelation. 'But I take care of Rex,' I cried. My mother counted with her very different, entirely speculative take on the situation, which sounded perfectly plausible in her eloquent delivery. She said that whatever my good intentions, I wouldn't have gone on taking care of Rex. I would have gotten bored or forgotten. I was, after all, a little boy and left it for my mother to pick up the pieces.

FEIFFERShe was always picking up the pieces. She picked up the pieces for my father when he let her down six or seven times a day. She picked up the pieces for my sister Mimi 100 times a day. I stood, steamrollered by the side of her drawing table, struck dumb by her brilliant advocacy. Earlier that day, she had, without warning, behind my back, given my dog away. And now she was explaining what she'd done under defense that suddenly hinted that the fault was mine. I did not take good enough care of Rex, not now perhaps, but sometime in the future, thus forcing my mother's hand. I left her no choice. As a result of my sure-to-be forgetfulness, my gross and future irresponsibility, she had to give my dog away.

FEIFFERAnd in so doing, she had done nothing less than save him. This fairytale farmer and his daughter, they would lavish on Rex the care that I, Dave Feiffer's son, and clearly every bit as unreliable, would not. Sometime next month or next year, my mother had me convincingly fated to fall down on the job. Fall down on the job was a copyrighted phrase of hers. So here I am, many years later, living in the middle of this Jewish mother joke, when she asked me, 'sonny boy, is there anything I ever did that you resent me for?' And I respond, 'no, ma.'"

REHMOh, Jules. What I didn't understand after reading that portion was how come she let you have the dog in the first place?

FEIFFERHow come she let me have him? Sorry, I didn't hear.

REHMWhy did she allow you to bring that dog into the apartment in the first place?

FEIFFERI think the dog was given to us, as I recall, by a relative. And anything within the family, in my mother's way of thinking, was doable. It had to be respected. If a family member, however close, however distance, did you a favor or gave you a gift, that had to be accepted. What happened after it, that's another story.

REHMSo how long -- or do you remember how long you had the dog?

FEIFFERI don't think I had the dog more than two or three months, if that long.

REHMOh.

FEIFFERAnd I do remember sitting -- I loved old-time radio. And that was -- I had these forms of escape. And I write about it in the book, the comics, radio, and when fantasizing ways out of the Depression, out of a child's life. And Rex would sit in my lap, and I'd stroke him. And we were a team. Now, I felt very alone in that apartment in that family. I had two sisters, and, you know, I was the only boy. And a boy with two girls around, one of whom was a communist and beating me up verbally, and the other was my sister Alice, who was so worshipful that I couldn't get away from her fast enough.

REHMHa.

FEIFFERSo I had my dog. And the dog was my alter ego, in a sense. And, now, my alter ego is gone.

REHMGone, just gone. How did your mother and father get along, considering the disappointment she was experiencing?

FEIFFERWell, it -- this is a '30s family, and husbands and wives got along because they had no choice but to get along economically. People who had -- might have been in love at one time now existed side by side. Divorce was not a big deal in those years. People didn't separate, or, you know, husbands sometimes disappeared. They were gone. But particularly, if you were poor -- and we were a poor family among other poor families, so we weren't that much different from other families. They existed side by side. Dad went out and made a living when there was a living to be made, and mom stayed home and ruled the roost. But mom usually -- in most of these families -- was in control of the domestic life. The difference here was that my father was unable to make a living, so my mother was in a position of having to do both, which embittered her, and understandably embittered her.

REHMMmm. Mmm. Jules Feiffer, tell me about the first break you had.

FEIFFERWell, I had been drawing cartoons as a kid and adored the cartoonists who I stole from, I swiped from. And one of them in particular was a man named Will Eisner, who was a hero to me. And Eisner was doing a weekly comic book supplement in newspapers called "The Spirit." And the Spirit was a hero who was just an excuse for Eisner to write and draw these fantastic short stories of eight pages in length in the 16-page section that he owned and edited. And I saved them and clipped them and studied them. And when I was 16 and needed a summer job, I looked him up in the phone book. Where I got the nerve -- because I had virtually no nerve -- I don't know. But there he was in the phone book, 37 Wall Street. I remember to this day the address.

FEIFFERAnd I went down, my heart pounding, and I walked into his office. And he was sitting in the outer office, the reception area, in the dark, working on the "The Spirit," the strip I idealized. And he welcomed me in, and he was very friendly, a little standoffish, and why not? And he looked through my samples, and he shook his head and basically he said in whatever language he used, that I had no talent at all. And I, then and now, take bad news by not hearing it. I mean, I basically blank it out because I'm not going to be able to deal with the enormity of it at the moment. So I changed the subject and began talking about his work since my work was a nonstarter here.

FEIFFERAnd the more I talked about his work, the more he realized that I had a dossier on him and that I'd seen everything he had done and loved every -- and can talk about it with intelligence. Now, he had three guys in the other office who were working for him, who were very capable assistants, some of them very good artists. But they didn't give a damn about his work. They thought he was old hat, old-fashioned. I mean, he had -- he got no feedback, no positive feedback from the people he depended on to help him do his work. But from me, he got this informed criticism, which he loved, and so he had no choice but to hire me as a groupie.

REHMAs a groupie that was paid?

FEIFFERNot paid for the first -- I mean, I was not worth anything, and that's what he offered me. He took me in the office and trained me. And everything he trained me at, I failed at. I was just a mess trying to be in this -- I had an ambition to do this work that apparently I had very little skill for. And until I got the opportunity at my -- at his suggestion because I begun to criticize his writing of the stories. I was such a smartass, you can't believe it. No talent and with a big mouth. And he said, well, if you think you can write one better, go ahead. And I did, and it was better. So I was the writer from then on. He acknowledged it openly. He liked what I wrote. I tried to write it in his style. And that's what I did for the next two or three years. I found my niche and a successful one ghostwriting "The Spirit."

REHMTalk about persistence. You know, in our first hour today, we were talking about the jobs market and how difficult it is, not only for young people but older people. There you were as a young person. People keep telling you, you have no talent. You don't listen. You keep on going.

FEIFFERWell, I had an uncle who I was very fond of, my uncle Eugene, who took me out to lunch every couple of minutes -- a couple months, I'm sorry -- and would say to me after I would give him this catalog of defeats and rejections that I've been going through, he said, why don't you go back to school? And I said, why? He said, well, you don't want to put all your eggs in one basket. And I would always say, I only have one basket. That the grownups that surround us -- some very well-meaning, some not so -- can be helpful to you. They can also be very dangerous to you because while giving -- making good sense of their advice, you can injure yourself. They can destroy your self-confidence. They can destroy your belief in yourself. They think they're doing the right job.

FEIFFERBut what you get, as a young person, is a sense of, I'm not believed in. I'm inadequate. Maybe I should go back into school. Maybe I should study accounting, something else. So, you know, to give up my ambition and do this. And as I say in the epigraph at the start of the book, do not let your judges define you. I wrote this book in large measure, hoping that young people could read it and get an understanding of how hard it is and how you must persist. And if you do persist -- and you must get some luck somewhere along the way, lots of luck -- you can have what you want. But part of it is to be able to define what they're saying that makes sense, and what they're saying that doesn't make sense to you.

REHMJules Feiffer, his new memoir is titled, "Backing Into Forward." And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." You know, I can remember, Jules, more than 40 years ago that when I began as a volunteer here at WAMU, people said to me, why are you volunteering your time? Why aren't you out there making money? And I said, because I want to learn. And here I am all these years later, so you're right. You have to make sure you differentiate from those who have an opinion you agree with about yourself and those you don't agree with.

FEIFFERAnd it's very difficult because sometimes, they could be right. And you have to know, or you have to guess when they have -- and even when they are right, if you think that they're wrong, and then you'll need to do what you have to do, you got to at least try it for some time longer.

REHMAbsolutely. Let's open the phones. We'll go first to Baldwinsville, N.Y. Good morning, Steve. You're on the air.

STEVEGood morning. Thank you for the opportunity.

REHMCertainly.

STEVEYour show has been a window to the world for me and a good companion for the long time.

REHMI'm so glad.

STEVEI remember at the beginning of that long time, being just a little kid -- I don't know what age -- but when you're first becoming aware of the world, a big, big part of that was in one little cartoon with a little wide-eyed, sappy-looking guy watching as things are floating out of the sky, just snow, but it's black. And he's watching television, and the things keep getting bigger. And the people on television finally morph into a General on the air, saying things like, big, black, floating specks are good for you. It was all about fallout during the atomic bomb test and all. And that comic and that phrase, big, black, floating specks are good for you delivered by a general on television, kind of opened my eyes at the time to the world. And I wanted to say thank you, Mr. Feiffer.

FEIFFERThank you. That was the historical "Boom!" which ran originally as a four-page supplement in The Village Voice back in the late '50s, I believe, and then became part of a book called "Passionella and Other Stories." And it was a time -- and it's hard to remember there was ever such a time -- when we still believed in what the government said. I mean, we as now -- and we have been since Vietnam days -- so skeptical of what government tells us that it's hard to believe there was ever a time that we took for granted that they were telling the truth, or mostly telling the truth. And that was during the -- still during the Eisenhower years, and we had atomic tests above ground and then underground. And as cows were being poisoned, and sheep were dropping like flies, we'd been told by the government there was no harmful effects of radiation in this test. And that went on and on and on. And "Boom!" was a satire about that.

REHMAnd as young school kids, we were told to hide under our desks.

FEIFFERYes. That was really going to help when the bomb fell.

REHMRight.

FEIFFERAnd we were told to hide under desks, or our children were -- I was an adult by that time -- in fear of the Russians who had the missiles but had no delivery system other than mailing it. So it was all part of the fear campaign that was part of the Cold War and the sensibility that sired the work I did.

REHMYou, I gather, have a different sense about this particular president, do you not?

FEIFFERWell, I've said that after Obama's acceptance speech, after his victory -- not, you know, after the victory and the Grant Park speech, I was so moved that he is -- as I've said any number of times, he's the first president that I feel good about since 1932.

REHMJules Feiffer, he is here with me talking about his brand-new memoir. It's titled, "Backing Into Forward." Short break. We'll be right back.

REHMAnd Jules Feiffer is here in the studio with me. We're talking about his brand new memoir titled, "Backing into Forward." Here's an e-mail from Gay in Greensborough, N.C. who says, "I've been a dancer and dance faculty member all my life, teaching in many universities around the country. We always had your cartoons on our bulletin board and love them. Where did they come from in your life? Who were they about?"

FEIFFERWell, that's funny. And I love hearing that because I've been doing these dancer cartoons, modern dancers doing dancing to the seasons, since 1957 seasonally. And I learned, maybe 20, 25 years into doing the work, that dancers themselves like them and clip them. And that means a lot to me, because -- well, you just want to be loved for the work you love. And I love doing these creatures in motion. My first girlfriend, the first one who slept over in my very first apartment downtown in the lower side on East 5th Street, she was a modern dancer. And I call her in the book, Jill -- that's not her real name. But you don't tend to forget that, and Jill was the person I modeled the dancers' body after and the character after. And as I moved further into romance and changed girlfriends as years went by, their bodies changed, the dancers changed and the looks changed. And none of this was deliberate.

REHMBut did you ever particularly go to the ballet to watch these dancers?

FEIFFEROh, well, this was modern dance as opposed to ballet. I like ballet and would go to Ballet Theater at the time and the New York City Ballet. But these were modern dancers where they'd be in little scrubby little holes in the walls, and the dancers would trudge forward on stage and explain the symbolism of what they're about to do. And it was always about bleakness and despair and destruction and gloom, and then they would leap around. And I just found it irresistible.

REHMLet's go to Paris, Ill. Good morning, Gary. Thanks for joining us.

GARYWell, thank you for allowing me the opportunity to talk to Mr. Feiffer.

REHMSurely.

GARYI have Mr. Feiffer's work on my bookshelf between the "History of Philosophy" by Will and Ariel Durant and Jack Kerouac going back to original copies of 1958 and his characters, like Passionella and Bernard Mergendeiler and Harold Swerg and Monroe.

FEIFFERMy goodness.

GARYI actually produced the Apple Tree...

FEIFFERDid you?

GARY...which included your work at Southern Illinois University in the '60s.

FEIFFERWell, that's wonderful.

GARYAnd anyway, I wanted to ask -- I want to talk about two things. Harold Swerg is my favorite character because he says, why can't we all be equal? And then that little ballet dancer -- and I worked with people in modern dance in New York City when I lived there. They -- your little dancer in her little world, the little short piece, talks about the world and whether it's a neutral or not. And it says, if you can just stay neutral, so...

FEIFFERI stand a chance.

GARYYeah.

FEIFFERYeah, it's a -- well, like Harold Swerg is somewhat different from that. The dancer in that one and many of the others were just trying to dance in order to stay even. I mean, that she knew that she headed for all sorts of disappointments, but she had to restore his spirit each time. Harold Swerg was this character -- and I think I wrote it originally as a story for Sports Illustrated -- was a man who was better than anybody at anything. But he had no ambition, and he didn't care. So all he wanted to do was not break records but equal records. And equaling records is, as it turns out in the story and in life, is un-American. You always have to break records. It's -- you have to surpass, and he wouldn't do that. He wouldn't be better than everybody else. He just wanted to be as good. And this enraged the powers that be, and that was the story.

REHMOf course, Gary talked about producing one of your works. What about you and playwriting? How did you move in to that?

FEIFFERWell, purely by accident. I mean, the book is called "Backing into Forward" deliberately because I -- all of the things that turned out to be work that I loved and work that changed my life with things I stumbled awkwardly into -- after the death of -- after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and Oswald being shot by Ruby a week later, I felt -- the months that followed -- that this was a country that was falling apart, and all forms of authority were losing their credibility. And I was looking around for some people to comment on that or read about it. And it seemed to me that nothing really was being done or said about what I saw plain as day, it seemed to me.

FEIFFERSo I tried writing a novel about it because I wasn't an essayist, and that was going nowhere. So I went off to this writer's community in upstate New York called Yaddo, and going over my notes for the novel, realized the novel was useless and hopeless. But I thought that this thing that I -- this idea I had, had to be rescued, and I was going to try it as play. I also understood that -- as a regular theatergoer -- that the plays I loved were the plays that usually got bad reviews and closed in a week. And the plays that were hitch and got Tony's and Pulitzer prizes were often the plays I walked out on. So I understood that if I wrote a play I really liked and thought was any good, it would close in a week. But I wrote "Little Murders" anyway. It opened on Broadway, and the first time around, it closed in a week.

REHMBut you didn't stop.

FEIFFERNo. I got a call from The New York Times, a wonderful fellow who was doing their gossip column. And his name was Sam Zolotow, and he sounded like Sam Levine -- and, you know, the actor -- and he said, okay Mr. big shot cartoonist, you wrote a (word?) play, now what are you going to do? And I said, Sam, I want to keep bringing it back 'till you guys get it right. And then it went off to London -- the first American play to be done by the Royal Shakespeare Company and won prizes. And it came back to the States, and Alan Arkin directed a brilliant production for the Circle in the Square Theatre. And it was a hit. And I was playwright. Go figure.

REHMBut you know, in a sense, it wasn't until you left The Village Voice that you began "Backing into Forward."

FEIFFERWell, no, not really because the Voice itself was a way of backing into...

REHMTrue.

FEIFFERI tried to do...

REHMTrue.

FEIFFER...these conventional strips, and no one would have me. And finally, the Voice was a final act of desperation to break into print doing work I really cared about. But without the Voice, it's questionable whether I would have had a career.

REHMNow, at first they didn't pay you.

FEIFFERWell, they didn't pay me for the first eight years. And then I discovered that they had -- they were paying everybody else. They had been for three or four years. So I went in to Dan Wolf, the editor, and said, I want to get paid. And he said, what do you want to get paid for? You're a mandarin. And I said, even mandarins have to eat.

REHMAnd then when you were making what, $75,000 a year?

FEIFFERAfter many years later.

REHMAfter many, many years...

FEIFFERYeah...

REHM...then what did they say?

FEIFFERWell, the Voice by that time was no longer the original Voice. It was not this free-wheeling, independent paper that gave writers a say. Now, it became a much more -- it was now a much more conventional, less interesting paper and corporately owned. And it wanted to cut costs, and so they brought in an editor to get rid of people. And since I was making more than anybody else in the paper because of longevity, he called me in to get rid of me. But he was so charming and so nice about it that it wasn't only an hour after our lunch, charming lunch, and I was walking through Central Park on my way home that I realized, I've just been shown the door. He did it by making me an offer that I was meant to refuse, that we'll still run you in the paper. We're just going to take you off the staff. We'll pay syndicate rates, which meant that my pay would have been cut by 75, 80 percent...

REHMWow.

FEIFFER...which -- and I had two children at home to support. This was a no, no. But they were so egregious about it. They wouldn't come to any settlement after all those years. I had -- most of the early prizes -- all of the early prizes the paper got were won by me, a Pulitzer and a George Polk and (word?) -- but none of that mattered anything to any -- at all to them. So all of this was so egregious that -- and that they were not going to continue my health insurance, my friend David Halberstam, the great -- late, great David Halberstam called up Joe Lelavelle (sp?) of The New York Times and said, you've got to do something about this. The next day, there was a front-page story in the Metro Section of The Times all about this. And they had asked me to do a cartoon on it, and I did. And suddenly, because of the lawful behavior of the Voice, I was a star again. I had been pretty much forgotten by that time, but, suddenly, their bad behavior brought me back.

REHMAnd that led to all kinds of other opportunities.

FEIFFERWell, left me to become an op-art cartoonist in The New York Times itself once a month. And that was wonderful, and I did that for several years. And so, you know, all sorts of other things.

REHMIsn't that something, how failure can do all kinds of things? I mean, for some people, failure can be the end. But for you, one failure after another led to one success after another.

FEIFFERAnd that's the point I wanted to make for young people who are taught something else entirely. We don't like to talk about failure in this country. It, too, is un-American.

REHMSpeaking of un-American, you certainly took on Joe McCarthy.

FEIFFERWell, McCarthy was actually out of business by the time I started. He was censured in '53, but the vestiges of McCarthy isn't. The sense of suppression was still rampant in '56 and '57 when I began. And it was interesting because I was a young man then and hanging out with young people. How loathe the people on you and just about everybody else was to offer opinions that were to the left or far to the left of official thought. And you check to see who was listening. If you worked in an office job, you didn't wear certain political buttons into the office, or you might get into trouble, might even get fired. It was -- it seemed as if liberals did not have First Amendment rights. And when I began the cartoon in the Voice, people who responded early to it weren't responding to the window of the humor. They were responding to what I was getting into print. And they would stop me and say, how did you get that published? They didn't think you could say that stuff.

REHMWow.

FEIFFERAnd since I had no job to lose and I had no career to threaten, I could do anything I wanted. I was at no -- they were in no position to hurt me.

REHMLet's go to Raleigh, N.C. Good morning, Carol.

CAROLWell, good morning. I'm so pleased to be here. And I'm listening to appreciating failure. I have a high school daughter who wants to be an artist like Mr. Feiffer, a comic artist. And in this economy, it's so difficult for me to encourage her to be an artist because I'm just so afraid for her. But I appreciate what you were saying about not letting your judges and other adults define who you are. But could you also give me some practical tips on how to guide her in her quest to be able to take failure and how to, you know, see which opinions to value and which ones not to?

REHMI think, for me, the story that comes to mind is that of Margaret Truman when she sang, and a critic here in Washington…

FEIFFEROh, yes.

REHM...Paul Hume, ripped her apart. And Harry Truman almost socked him...

FEIFFERHe wanted to punch him in the nose.

REHMYeah, he really did. But it was also Harry Truman who said, find out what your child wants to do, and support that child.

FEIFFERAnd support is the operative word here, which means you can't do it for them. And you can't be overly supportive so that they feel that they're going to disappoint you terribly. They have to be doing it for themselves. And basically, you have to let them go and give them license. Give them permission to follow and fall on their face and follow and fall on their face. And there's a lot of falling on your face. That's part of the game. That's part of the ritual, and it has to be understood. And I think what you can do with your daughter is encourage her to follow this pursuit while also encouraging her to learn other things, and, you know, it is hard making a living in this economy. But it has always been difficult for creative people, and the money is not necessarily there in the beginning and may never be necessarily there. So she may have to do other things in order to pay the rent, but she can have the art and do these other things.

REHMCarol, good luck to you and to your daughter. Thanks for calling. And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Finally, to James in Jacksonville, Fla. Good morning. You're on the air.

JAMESGood morning, Diane.

REHMHi.

JAMESI was just wondering, Mr. Feiffer, if there's any contemporary artists possibly in comic strips or even in the comic book media that you may hold in high regard or some maybe that even opposed you in the way you opposed Mr. Eisner?

FEIFFERWell, the form, as we all know, is disappearing down the tubes. There are still some very good people doing them. Gary Trudeau remains at the top of his game. And "Mutts" is still a very entertaining, beautifully drawn comic strip, and there are several others. But the real action is in the graphic novels and -- a term I hate -- an alternative cartoonist. David Small did a brilliant memoir last year called "Stitches" about his boyhood, and that's a beautiful work of art. And there's an artist named Craig Thompson who did a graphic novel called "Blankets." And there was wonderful Dan Clouse, (sp?) and Chris Ware's work is extraordinary. There are just wonderful people out there. And if it's not in comic books or comic strips, and you look into the alternative work, you see that they are going through what will later be called a Golden Age.

REHMHmm. James, I hope that helps. Thanks for calling. Jules Feiffer, you've always had such troubles with authority figures, and now you have become the authority figure. Are you okay with that?

FEIFFERI'm very happy with that. If only my family would listen.

REHMJules Feiffer and his new memoir is titled, "Backing Into Forward." We have some of his Superman cartoons up on our website at drshow.org. Thank you so much for being here.

FEIFFERThis is always a pleasure from me. You're a delight. Thank you.

REHMThank you. Thanks for listening, all. I'm Diane Rehm.

ANNOUNCER"The Diane Rehm Show" is produced by Sandra Pinkard, Nancy Robertson, Jonathon Smith, Susan Nabors, Denise Couture and Monique Nazareth. The engineer is Tobey Schreiner. Dorie Anisman answers the phones. Visit drshow.org for audio archives and CD sales, transcripts from SoftScribe and podcasts. Call 202-885-1200 for more information. Our email address is drshow@wamu.org. This program comes to you from American University in Washington. This is NPR.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.