Exclusive: Your Questions Answered By Erik Larson

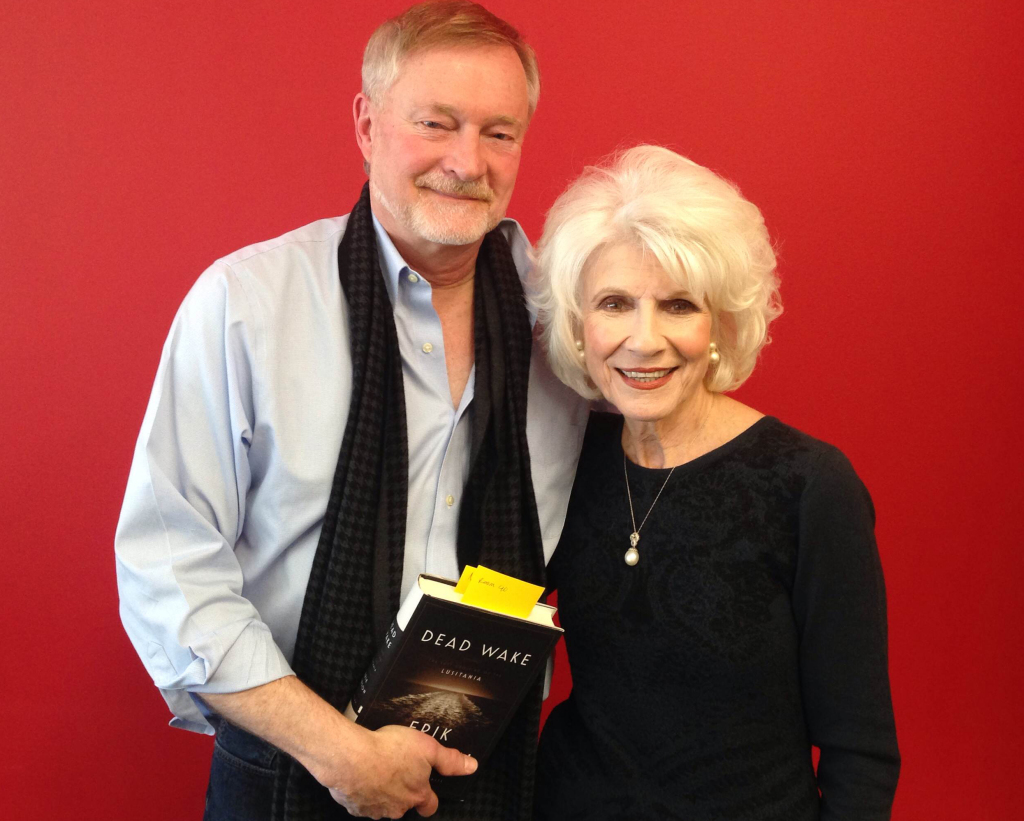

Erik Larson and Diane Rehm after their March 18 interview.

After coming on the show March 18 to talk about his new book, “Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania,” Erik Larson sat down with us to answer questions submitted by listeners before and during the show.

Question: Why the switch from journalism to nonfiction? Is your approach different?

Erik Larson: It was very much an evolutionary process. I started doing longer and longer pieces, first for newspapers, then for magazines. Then I began to realize with the kind of work I was doing for magazine pieces, I might as well do a book, because it would last a lot longer on a shelf than it would a news stand. So really one thing led to another, and suddenly, I was profitably doing books as my day job.

Finding ideas for my next project is really the hardest part. I never know what the next project is going to be when I finish a book. For me, an idea has to work on a lot of different levels if it’s going to be the kind of thing that I can write in my way. I do what people like to refer to as narrative nonfiction … In order to do that kind of nonfiction you have to have certain things: It has to be interesting, it has to be something I can live with for three or four years. But also very important is to have a built-in narrative arc, something that makes the action ascend in a compelling way toward a climax. And then very important of course is it has to have a very rich archival base, because you have to be able to find the right material if you’re going to have to tell a nonfiction story in that narrative form.

Q: How much time do you spend reporting and researching before you are sure you are going to have a good story that will fill an entire book like this? Have you ever had to scrap a project because you just couldn’t dig up enough material?

EL: I spend about two years researching full time and two years writing. And then there’s overlap in between: There’s periods when I’m researching and writing at the same time because there’s a point at which you have to start writing because it feels like you’re ready.

I’ve never had to scrap a project. By the time I actually get into it, I have committed to it and my publisher has committed to it. So I have a very good idea about whether it’s going to work or not because I always do a very detailed book proposal beforehand. It’s based on a lot of advance research. For me, a book proposal means I’ll have a sample of the opening chapter … I almost invariably know exactly how I’m going to start and how I’m going to end it right away. I also do an essay about what the book is going to be, why people are going to want to know about it, and then the key is a chapter-by-chapter outline, little capsuled chapters, to determine the structure of the narrative. That tells you where the energy is in the story, so I already know the shape of the book. For me to give up on the book at that point in the process, something very extraordinary would have to happen … by extraordinary I mean David McCullough comes out with a book on the same subject. Then I’d say, that’s it, I’m done.

Q: How hard is it to get into all of the archives and libraries? Do some not want all the facts uncovered?

EL: Access to archives is almost invariably uninhibited. There are a few archives that are private that are a little bit trickier, but I had no issues whatsoever with someone trying to keep me out of their collections. The only time I had any kind of resistance is when I asked to see photographs of morgue victims of the Lusitania. These are pictures that were taken days after the sinking … I knew they existed and I asked to see them, and at first they said no. They decided it was too insensitive. But being a reporter from way back, I pushed a little bit and asked if they could at least take it up to the next level for review. [In the end], they let me look at them though they did not let me take photographs. I asked what changed and [it turns out] the chief archivist is a big fan. That helped

Q:How do you choose characters?

EL: There’s no artistic license. [In nonfiction,] you can’t make things up. You’ve got the stuff or you don’t. The characters that I choose, in the case of this book, apart from the military and government officials, are in the book strictly because they left enough detail to let me tell their stories the way I like to tell them.

Q: Do you have a favorite among your books?

EL: No. No. I mean, you’d have to ask me if I had a favorite among my children. Some book shave done commercially better than others, but I don’t have a favorite.

Q: Your book is text only. Why not some photos or other art?

EL: My goal in writing history is to produce as rich an experience as possible. It’s not to present traditional history, it’s not to inform, perse … you can do that in your PhD. My goal is to produce this rich historical experience. So my ideal scenario is you sit down with my book and sink into the past and emerge with a sense of having lived in the past. The problem with photographs, especially in a nonfiction trade hardback, is that reproduction is not high quality, the pictures are small, they often fail to capture what really was happening and beyond that, more importantly, they’re often presented in a signature, which is a six page glossy insert. Sometimes there are multiple inserts. The problem is these things act as a lighthouse beacon for readers, they slip back to look at the photographs and that takes you out of the dream; that takes you out of this historical world that I’ve tried so hard to reproduce. I don’t want to blow it by having you flip back and look at these lousy photographs.

Also, let’s be frank: If you want to see pictures of the Lusitania, fire up your computer and you’ll find much better images than you’d ever find in my book.

Q: You like to write historical nonfiction, but what do you like to read?

EL: For pleasure, I read almost invariably fiction. I like literary detective novels but I’ll read almost anything. I loved Jonathan Tropper’s “This Is Where I Leave You.” It’s hilarious. I’ve been on a binge of reading Scandinavian detective novels, I love those. I just reread The Maltese Falcon. I’m reading now a book called Smilla’s Sense of Snow.

Q: What writers have influenced your work?

EL: It depends in what context. If you’re talking strictly about narrative nonfiction, the book that really sort of helped me think there might be another way to tell history was David McCullough’s “The Johnstown Flood.” It’s a very good, really powerful narrative, very interesting.

But if you’re talking about writing in general, prose style and so forth, really I go back to Hemmingway. He might not have been the nicest person in the world … but the fact is he was a great writer. And what I love about him is the austerity of his prose. It’s very clean, simple lines. He is the master of the art of not saying of not telling, everything is oblique and that’s very powerful. Along the same lines: Chandler, Hammett, Steinbeck.

Q: There have been rumors about a “Devil in the White City” movie adaptation. Can you comment on that?

EL: It’s not a rumor. It’s been under option for a long time by Leonardo DiCaprio, who wants to play a serial killer. The option is still alive … I’m not sure where exactly it is, I try not to get involved in Hollywood. An option is also alive for “In the Garden of Beasts,” by Tom Hanks. He’s interested in playing the ambassador in that story. So we’ll see what happens.