Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

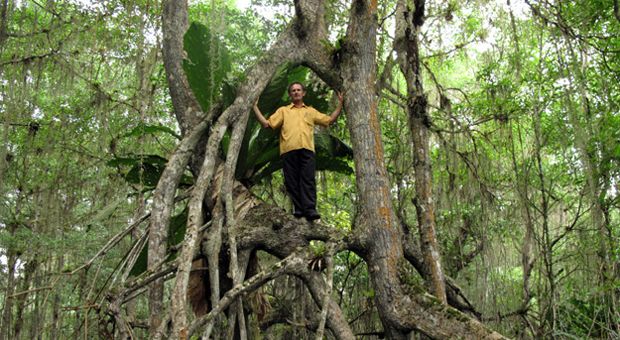

Warne in a Mangrove forest

John Steinbeck once said “no one likes the mangroves.” But New Zealand marine biologist Kennedy Warne argues they are simply misunderstood. There are seventy species of mangroves, ranging from trees to shrubs to ferns. What defines them is their unique ability to thrive in heat, mud and salt that would kill an ordinary plant. Mangrove forests support a wealth of animal and plant species. They provide food, medicine, work and homes for millions of coastal people. But development and shrimp aquaculture are threatening their existence. Warne explains the importance of these rainforests of the sea and how we can help protect them.

Many people have never heard of mangrove forests, but they are nurseries for a vast variety of animals and plants. They act as supermarkets of the sea for humans, providing shellfish, crabs, honey, timber and charcoal, and they’re also good storm barriers. To shrimp farmers and real estate developers, they represent a good investment, but at the cost of local ecosystems and the people who rely on them. Environmentalist Kennedy Warne has written a book about what he calls the tragic disappearance of these rainforests of the sea.

How Shrimp Farms Are Harming Mangroves

Over the past 40 years, most industrial shrimp farms have been located in areas where Mangroves grow – at the borders of the land and the sea. The forests are removed, and shrimp farms have been developed, mostly in parts of Southeast Asia and Central America. Warne estimates that anywhere from 50 to 70 percent of all mangroves have been removed over the past 4 decades.

They May Smell, But They’re Still Wondrous

There is a wide variety of mangroves – as many as 70 species, according to Warne, including hibiscus, holly, and palm. What they have in common is the ability to withstand a saltwater environment that would kill an ordinary plant within days, or even hours. But there’s not much oxygen in the soil in a Mangrove forest, which can contirbute to a pervasive sulphurous smell, and the swampy conditions are ideal for mosquito breeding. They serve as such a huge source of food in many countries that Warne refers to them as an “ecological Swiss army knife.” Mangroves are also one of nature’s best carbon sequestration plants, which could help diminish the ill effects of climate change.

Nature’s Barriers

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami made some countries in Southeast Asia and the wider region realize the cost of having removed some of the natural coastal barriers like mangroves. Warne admits that even mangroves couldn’t have stopped a 30-foot high tsunami wave, but climate scientists are predicting an uptick in more forceful hurricanes and cyclones. But the arguments for saving the mangroves for barrier reasons is difficult to make in the face of the value of those areas of land. For commercial fisheries, an acre of Mangrove area could be worth as much as $30,000, and the people who live alongside the mangroves have traditionally not had a strong political voice.

What Can The Rest Of The World Do?

Consumers everywhere should try to make a connection to where their food comes from, Warne said. Ninety percent of the shrimp that comes in to the U.S. isn’t coming from wild shrimp fisheries, Warne said – it’s coming from exports from the developing world. There is also a move in the political arena toward certifying the sustainability of shrimp. Warne would also like to see greater social justice for the people of the mangroves who have lost their way of life and, in some cases, their livelihoods.

You can read the full transcript here.

Excerpted from Kennedy Warne’s “Let Them Eat Shrimp: The Tragic Disappearance of the Rainforests of the Sea.” Copyright 2011 by Kennedy Warne. Excerpted here by permission of Island Press:src=”http://www.scribd.com/embeds/74154851/content?startpage=1&viewmode=list&accesskey=key-9ofan33yhqv6enax4b8″ data-auto-height=”true” data-aspect-ratio=”0.666666666666667″ scrolling=”no” id=”doc17966″ width=”100%” height=”600″ frameborder=”0″>

MS. SUSAN PAGEThanks for joining us. I'm Susan Page of USA Today sitting in for Diane Rehm. Many people have never heard of mangrove forests, but they are nurseries for a vast variety of animals and plants. They act as supermarkets of the sea for humans, providing shellfish, crabs, honey, timber and charcoal and they act as natural storm barriers.

MS. SUSAN PAGETo shrimp farmers and real developers, they represent a good investment, but at the cost of local ecosystems and the people who rely on them. Environmentalist Kennedy Warne has written a book about what he calls the tragic disappearance of these rainforests of the sea. The title is "Let Them Eat Shrimp" and he joins me in the studio. Welcome to "The Diane Rehm Show."

MR. KENNEDY WARNEKia ora, Susan...

PAGEWhat kia ora?

WARNEThat's the New Zealand greeting.

PAGEIs that right?

WARNEYes, that's the Maori greeting.

PAGEOh, very nice, we invite our listeners to join our conversation. Later in this hour, you can call our toll-free number 1-800-433-8850. Send us an email at drshow@wamu.org or find us on Facebook or Twitter. Now the title of your book "Let Them Eat Shrimp," that might mislead people about what you're talking about. What does that title mean?

WARNEWell, it comes from Marie Antoinette, of course, who displayed a colossal disconnect with her people when she said let them eat cake. And it seemed to me that it was not inappropriate for us to use a title which looks at how first-world appetites for a luxury seafood have collided with third-world livelihoods and ecosystems. And that's why we went there with shrimp because the shrimp aquaculture in the developing world has been the largest contributor to the decline of these rainforests of the sea.

PAGESo the appetite by many Americans for shrimp...

WARNEYes.

WARNE...has encouraged the development of these shrimp farms...

WARNEYes.

PAGE...that have destroyed a lot of mangrove forests?

WARNEYes, industrial shrimp farming has over the past 40 years been largely located in mangrove areas which are the borderland between land and sea at the expense of those very forests. So the forests are removed, shrimp farms are put in and that is a juggernaut that has led to rolling destruction of mangrove areas in parts of Southeast Asia and Central America. Fifty, sixty, seventy percent of mangroves have been removed in the last 40 years.

WARNEThe current rate of destruction of mangroves is still around 1 to 2 percent a year which is roughly the same as say Amazonian rainforests.

PAGESo let's take a step back. What is a mangrove?

WARNEWell, mangroves are a group of plants. I think many people have the idea they might just be one type of plant, but there are actually 70 species of mangroves and they span a wide range of families. There's hibiscus. There's holly. There's some plumbagos. There's a myrtle. There's a fern. There's palm. And there are lofty, 130-foot tender trees which create cathedrals of nature. And so all of these plants, what they have in common is the ability to withstand a salt-water environment that would kill an ordinary plant within days, if not hours.

WARNESo I think of them as the sultans of salt, the princes of the tide that can occupy a very difficult environment because they -- when the tide goes out, they're exposed to baking dislocating heat. And when the tide is in, they've got to cope with salt water that would love to suck all the sap, you know, through osmosis that would just -- it's a very challenging environment for a tree to live in.

PAGENow, you clearly love mangrove forests, but your description of them in your book makes them sound not 100 percent appealing, I have to say, lots of mosquitoes. It's very swampy, smells kind of bad.

WARNEYes, there's a reason that mangroves are often described as swamps. I prefer not to use that term because it just seems inherently disrespectful when you have spent time in these forests which are sublime places to be. But yes, they -- you will sink to your knees in mud if you venture in and they have a lot of sulphurous -- they're an anaerobic environment. The soil tends to not have much oxygen in it and so they are -- they're not for the faint-hearted, but they are for anyone who wants to experience a wonderful ecosystem, a wonderful habitat full of very strange and unique creatures.

WARNEThere's so many plants and animals that are restricted to mangroves or -- and they are a wonderful array from snakes and terrapins. And in Cuba, there are two rodents of unusual size that live only in mangroves. Forty-eight species of birds are primarily or exclusively found in mangroves so there's a whole world in there that most people don't know about.

PAGEAlso, very pragmatic reasons, that they serve in many countries as a huge source of food.

WARNEYes, well, you covered that earlier. I call them an ecological Swiss army knife with a blade for every purpose. They're superb barricades against storm surges and gales and hurricanes and so forth that would erode the land. They stabilize sediments going in the other direction. They filter the runoff from the land into the sea. They supply a drip-feed of organic carbon that sustains inshore ecosystems. It sustains a wide range of fisheries. They are nurseries for an extraordinary number of fish species and then another point I explore is that they are carbon sinks par excellence.

WARNEThey are among the highest sequestering carbon sequestering ecosystems on earth so they have this array of environmental services, but then as you say there's a whole world of people who rely on mangroves. They are their supermarkets and they supply everything from lumber to honey to medicinal products and food and livelihoods.

PAGEOur phone lines are open. You can give us a call 1-800-433-8850. We'll go to the phones in just a few minutes. You talked about the role of mangrove forests in carbon sequestration. So what does that mean exactly? That means that carbon that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere is caught there?

WARNEWhat it particularly means is that when the leaves and twigs and branches of a mangrove tree fall into the soft mud in which they live, then instead of being oxidized, they tend to sink down into that mud and then all that organic carbon that's in those tissues gets locked up. It doesn't get oxidized because, as I said, there's very little oxygen in mangrove sediments. And so it can just remain there for a 1,000 years like it's a carbon jail and all that carbon gets trapped there.

WARNEUnfortunately, when mangroves are bulldozed for coastal development or for shrimp ponds, all that carbon gets exposed into the atmosphere and that gain you've had in carbon storage is suddenly released and, of course, contributes to increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

PAGEYou mentioned also honey as one of the many things that...

WARNEIt's delicious, Susan.

PAGE...you can get.

WARNEIt's unbelievably good.

PAGEYou wrote about honey collectors...

WARNEYes.

PAGE...in Bangladesh.

WARNEYes.

PAGETell us about that.

WARNEWell in the Sundarbans which is the largest mangrove expanse on earth, shared two-thirds, one-third between Bangladesh and India there is a guild or a group of people, the Muali, who go into the forest and find wild honeycomb which is just hanging in luscious, large droops from branches and they cut that down and that's their livelihood.

WARNEAnd it's dark. It's intensely fragrant, has a kind of a smoky flavor. I can taste it now. It was wonderful going in with these honey gatherers.

PAGEDangerous work, though, because there are all these tigers...

WARNEThat's right.

PAGE...in the mangrove forests there.

WARNEThat's right. The supermarkets of the Sundarbans have tigers in the aisles and the -- when I visited, it was the very beginning of the honey gathering season, but already four colleagues of the group that I went with had fallen to the paws of the Royal Bengal tiger, the only tiger...

PAGEMeaning they had been killed?

WARNEYes, yes. Sorry, I just got a bit poetic there, but that's right. Perhaps 100 or more, no one really keeps records of the numbers who die, but I met several people who told harrowing stories of trying to escape from tigers. So they're the only tiger -- probably the only big cat that lives in a salt water environment. And you take your life in your hands if you go into that place, but about a million Bangladeshis per year rely on the Sundarbans mangrove forest for timber, for honey, for thatch from the mangrove palm and for fishing.

PAGEAnd the honey collectors use some religious rituals to try to protect them from the tigers. What do they do?

WARNEThey do. Well, if you're Muslim. you would probably have a little metal amulet on your arm and inside that would be a verse from the Koran. If you're a Hindu, you would make pooja at one of the many shrines that are around the edge of the Sundarban forest to Bumblebee, the goddess of the forest who traditionally overcame and conquered the evil tiger god, (word?) and so you would come and make an offering to Bumblebee.

PAGEWe're talking to Kennedy Warne about his new book, "Let Them Eat Shrimp: The Tragic Disappearance of the Rainforests of the Sea." We're going to take a short break and when we come back, we'll go to the phones. We have some callers who have had their own experiences with the mangrove forests, stay with us.

PAGEWelcome back. I'm Susan Page of USA today sitting in for Diane Rehm. This hour we're talking with Kennedy Warne, a New Zealand environmentalist about his new book "Let Them Eat Shrimp: The Tragic Disappearance of the Rainforests of the Sea." And we're going to go to the phones and let some of our listeners join our conversation. Let's go first to Myer. He's calling us from Houston. Hi, Myer.

MYERHi, how are you?

PAGEGood.

MYERLove your show or Diane's show. But I lived in Belize where mangroves were pretty much blanketing the coast. And I guess I don't know other parts of the world where there are mangroves, but they really were swamps, but that's not a negative. People love swamps like they love the Arctic. I mean, someone as passionate like your author here is passionate about it and people are studying things that are unpleasant for the rest of us, it's their passion.

MYERI am never for destroying any ecosystem at the expense of the pleasures of the rest of humankind so we can have more shrimp or whatever. But it's a very mixed blessing. I mean, the mosquitoes are terrible when you get near the swamps. The smell is bad. I think, if I'm correct, since it's salt water coming something into estuaries or rivers, there's lots of crocodiles or alligators nearby and snakes. He is absolutely right about the honey. Mangrove honey is just delicious.

MYERBut Belize is both a blessing and a curse because it does protect them from the storms. But without mangroves, they would have the pristine beaches like some parts of Mexico would have. Instead they have the islands that are outside the mangrove swamps. But the coast of Belize itself is not very pleasant to be along if you wanted to go and enjoy yourself. So, you know, for them, it's a mixed blessing. It takes away a lot of tourism in that regard.

MYERBut I'm glad to hear that he's impassionate and I'm glad to hear that he's pointed out some things about the carbon footprints and other things that I did not know about. So I appreciate his research and his passion.

PAGEAll right, Myer. Thanks so much for your call.

WARNEYeah, thanks. Yeah, well, Belize is a place that I've been fortunate to spend some time in. And, in fact, the problem there as elsewhere is that great swathes of those mangroves have been removed for resort development and enormous shrimp ponds. And, yeah, this -- the shadow of shrimp agriculture is long and extensive and has even affected places like Belize, which really rely on ecotourism too and market themselves in that way.

WARNESo countries like that have to make up their mind which is more important, retaining the integrity of their ecosystems or going for the quick buck that can be obtained through conversion of these forests to other purposes.

PAGECourse, that's a tough call for countries that are trying to develop, who have big economic problems. What is convincing in that debate to convince nations that have these mangrove forests to preserve them?

WARNEYou know, I think in the wake of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami a lot of countries in Southeast Asia and in that region really started to count the cost of having removed the coastal barricades. Okay. A 30 foot tsunami wave, even a mangrove can't stop that. But given the likely increase in hurricanes and cyclones that climate scientists predict, it's not a smart move to remove the bio shields that protect your shorelines. That's from an environmental point of view. And any of those environmental ecosystem services, as they call them, that mangroves provide are cogent reasons for holding on to these ecosystems.

WARNEAs nursery for commercial fish species, they estimate that an acre of mangroves could be worth as much as $30,000 for its nursery function for commercial fishing. Why would you remove the nursery for the fish that your people want to catch? But I think for me, as I explored this initially with National Geographic as a story, I mean, and then through the book, I realized that -- and the greatest motivator for me was the people of the mangroves, that there are countless millions who have been displaced from their traditional areas of food gathering and livelihood.

WARNEUnfortunately these are people that are readily marginalized. They are not usually people with a strong political voice. They can be overlooked and that's what's happened in many developing countries. There's governments that have been desperate for foreign exchange have had a pretty cozy relationship with entrepreneurs who seek to use what is a common resource, the mangrove land, and converted to a profit-making enterprise. And the invisible people are the people of the mangroves who lose their opportunity to not just make a livelihood but in many cases to live.

PAGEIt requires the government of a developing nation to take a long term view of things to protect the mangroves. Is there a place you'd point to that's done an especially good job?

WARNEOf negotiating...

PAGE...protecting the mangroves, of preserving that resource against the kind of siren call of development or of shrimp farming?

WARNERight. I wish I could say there was but in almost every case the waking up process seems to be just beginning. It's interesting that, for example, a few years ago in Ecuador the constitution was changed to enshrine and protect the so called rights of nature. And many jurisdictions, Brazil as well, the environmental legislation claims to preserve, protect and acknowledge the rights of all citizens to clean water, to access to natural places, to obtain a livelihood and so forth. But the reality is that shrimp ponds, shrimp farmers continue to get new licenses for new areas. And it's still going on.

PAGEIt's a distressing thing that you can't name a nation that has done an admiral job, an especially good job. Where are the places that cause the most concern where you think there's been the greatest loss, the most alarming situation when it comes to this ecosystem?

WARNEIt's been spreading around the developing world. I should point out that mangroves are pretty much found in a belt between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, so that's where you find them. Initially the shrimp development was in Southeast Asia and then it quickly spread to Latin America. Ecuador was one of the very first to jump on the shrimp bandwagon.

WARNEIn all of those places, as I said earlier, we're looking at 50, 60, 70 percent mangrove loss. There is now protection. Ecuador does protect a sizeable chunk. I think it's like a panic reaction, we're going to lose the whole lot. So the very northern area of the Esmeraldas is a large and wonderful mangrove protected area. And I would say that yes, legislation is coming into many developing countries to halt -- or to slow down if not to halt the conversion of mangroves. But it's been a long time coming.

WARNEAnd the real key here is which of these countries are committed to mangrove restoration? It's imminently possible to restore mangrove forests to flourishing and productive ecosystems. But not many people are lining up to do it. It's not too expensive. Experts have estimated that about $40 an acre will allow you to have a fully ecologically restored mangrove forest. Within 30 years you can get back the fish, the species that live above ground, the microorganisms in the soil. But sadly we're a long way away from even -- break even or no more net loss.

WARNEAt the moment ecologists worry that by the end of this century in many places mangroves may be extinct as a functioning ecosystem apart from little patches that have been protected. Unless we slow down the right of loss and begin to replant we won't have those ecosystem benefits and services that mangroves provide.

PAGESo we've talked about the obligations that we hope -- or the role that we hope nations in the developing world will take to protect mangrove forests. What about Americans and other people in the developed world. Is there anything that they can do to try to help?

WARNEThe first thing I think is to -- for consumers to begin to make a connection with where their food is coming from. Most people probably don't know that 90 percent of the shrimp that comes into the U.S. isn't coming from wild shrimp fisheries. It's coming from exports from the developing world. So the natural thing to do is to say, where is my shrimp coming from.

WARNEAnd many people now -- it's a growing movement -- people want to live -- eat more intentionally. They want to eat more ethically. They want to eat with a sense of connection of knowing and connecting their act of eating with the producer, whether that producer is a farmer whose products are coming to a farmer's market or whether it's sustainably caught fin fish. And I would say ask that question and find out where the shrimp is coming from. That's from a consumer point of view.

WARNEThere are some -- there's activity in a political arena, the idea of certifying shrimp, certifying its sustainability and so forth. This is a long way from being, I would say, a completed process or a satisfactory process because the people of the mangroves don't really have a voice. As I said, they're marginalized. And the loss of mangrove forests that has so deeply impacted their lives, the conversation at the moment is more about environmental benefits and say sustainability from an environmental point of view, but what about from a social justice point of view? And that's what I'm also raising in the book.

PAGEI'm Susan Page and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We're taking your calls, 1-800-433-8850. Let's go to Amy. She's calling us from Baltimore. Hi, Amy.

AMYHi. Thank you so much for taking my call. I go to Costa Rica I guess the last six years. And I took a trip down to the mangrove swamps down there along the Sierpe River just outside the Osa Peninsula which is just a huge national park. And I think Costa Rica does a pretty good job of replanting rainforests that were taken down by the old united fruit companies back in the turn of the century through the '20s. And now that they're completely out I think that they do look at their mangrove swamps as a tourist attraction.

AMYI didn't see, at least outwardly, any of these shrimp ponds that you're talking about. I saw all of the fantastic duties that mangrove forests have to offer. I never really knew until I saw it. So when we're looking at other parts of the world are they looking at maybe doing state parks to protect the mangroves? And secondly, I shop at -- I hope this is okay to say. I shop at Costco, which is a huge warehouse, obviously, for food. They sell the best shrimp and they all say marked from Taiwan, but it doesn't say shrimp ponds on it. So how am I to know if it's from a shrimp pond or caught in the wild?

PAGEYou know, Amy, that's a great question. How do you know?

WARNEWell, I think these days if you're providing wild shrimp you're going to say it loud and clear because -- and I know that U.S.-caught shrimp really markets itself as wild shrimp to distinguish itself from the rest. If it doesn't have wild on it I think you're pretty well guaranteed that it came out of a pond. Thailand is probably the biggest exporter to the U.S.

WARNEAnd if you go to Google and look on -- zoom in on Google maps, you will see around the -- huge areas of Thailand little rectangles. They are shrimp ponds. Go to near Bangkok. You will just see wall-to-wall rectangles that are shrimp ponds. So, yeah, you can be pretty sure that if the distributor or the marketer isn't saying wild caught, then it's going to be industrial shrimp that has a whole suite of problems.

WARNEI'm glad, Amy, that you mentioned Costa Rica. That's actually probably -- I haven't personally visited Costa Rica but that would definitely be a shining light. Because I know that the Costa Rican government has made a lot of decisions based on positioning their country as an ecological destination as opposed to other, you know, types of market and commerce.

PAGEAmy, thanks so much for your call. Here's an email from Cass who writes us from Alexandria, Va. Cass writes, "In 1972, 1973 I helped design a project to rehabilitate, modernize and expand brackish water aquaculture in Indonesia. This culture is many centuries old, was fully integrated with sweet water paddy farming upstream and sustainable within the coastal ecosystem.

PAGEI visited the area 17 years later and was aghast at the negative development since. The ponds have taken over the entire coastline. The mangrove had gone so there was no filtering the huge influx of sewage discharge from the fast-growing cities and polluting enormous areas of the sea. Most telling, disease due to bad management has almost wiped out shrimp culture. How to repair this damage?"

WARNEThat's a very good point indeed. Combination growing of mangroves with types of fisheries called silver fisheries has been practiced for a very long time in parts of Southeast Asia. And this is low intensity but highly sustainable type of aquaculture. That's being replaced by high intensity industrial style aquaculture where they aim to get three crops a year out of a single pond. And when that pond is exhausted it becomes toxic. Unfortunately the pattern has been just to simply knock over a few more mangroves and start again.

WARNESo there are options for sustainable aquaculture. And I'm actually struggling to remember the last part of the question.

PAGEWell, the question was how to repair them. What could be done?

WARNEOh, how to repair, yes. Well, that's -- I touched on that before that if there is the political will that even ponds that have been abandoned, they've been baked in the sun and they're acidic and they seem malevolent and unable to grow anything, if they are correctly reconfigured so that salt water -- the seawater can get in, even places like that can be readily restored and replanted.

WARNEAnd the -- a lot of the techniques of mangrove restoration have been developed here in the U.S. And you can go to places in Florida near Ft. Lauderdale and see a 1500 acre area of restored mangrove where previously -- there's one particular place. I think it's called West Park that was, you know, tomato fields and had been wonderfully replanted. And you can go there and walk among these trees and see the fish that have returned to that place.

PAGEWe're talking to Kennedy Warne about his book "Let Them Eat Shrimp." We'll continue our conversation after just a short break. Stay with us.

PAGEWelcome back. I'm Susan Page of USA Today, sitting in for Diane Rehm. We're talking with Kennedy Warne about his new book, "Let Them Eat Shrimp: The Tragic Disappearance of the Rainforests of the Sea". And of course one of the big topics has been on the role of shrimp farming on the mangrove forests. We now have a caller, Wally Stevens. He's executive director of the Global Aquaculture Alliance. Mr. Stevens, thanks for calling in.

MR. WALLY STEVENSThank you for having me.

PAGENow, you wanted to make a point I think. Please go ahead.

STEVENSYes. Our organization recognized, probably 10 to 15 years ago, that there were issues with the mangroves relative to shrimp farming. And we have worked very diligently for that last 15 years to make sure that that practice is not allowed. We've set standards by which shrimp farming can be conducted. We set them in most every country around the globe. And we set them at the behest of the retail and food service marketplaces in most developed countries.

STEVENSSo the practice of shrimp farming as a cause for mangrove destruction, hopefully, is ancient history. It is not current practice.

PAGEAll right. Well, Mr. Stevens, if you could just hold on. I'd like to give Kennedy Warne a chance to respond.

STEVENSSure.

WARNEHi, Wally. Oh, no, I do appreciate that the industry is trying to address this. I think from my recent visits to many countries where the, if you like, the sharp end of the practice is occurring, shows that despite the -- I guess it's something to do with the length of the supply chain, but in many places the problem is still occurring. The diggers are still there. The bulldozers are still there. The grassroots people, the crab collectors, the cockle gatherers, the people who seek to make their livelihood from mangrove areas, they continue to send me pictures and disturbing reports of what's happening.

WARNEI think it's probably an issue of regulation. It's probably an issue of monitoring. These places are generally far from ready observation. And so I know that the industry is moving in the right direction. And I know there are some excellent examples of sustainable shrimp farming that are being developed, even here in the U.S. and in Belize. And these are all things to applaud, but I find myself still haunted by the words of, you know, a particular mangrove activist in Honduras who said, they have turned the blood of my people into an appetizer.

WARNEAnd I'm sorry, but I'm still seeing a slow -- well, I'm still seeing the legacy of that previous history. It seems to be difficult to transition out of that.

PAGEAnd, Wally Stevens, you set these standards. How are they enforced?

STEVENSThe standards are enforced by certification bodies that are independent from industry. They send auditors in on an annual basis to determine if a facility is abiding by these standards. We have 350 million pounds of shrimp today, certified to standards that include environmental issues relative to mangroves and other environmental challenges. And we have them in every country, as I say, that is producing shrimp. So it's an independent verification that takes place. It's not a perfect world. And there are some countries that have many small facilities that probably, at this point in time, cannot meet our standards. But the vast majority of shrimp consumed in the United States is certified to our best aquaculture practice standards and is not shrimp that is causing harm or has caused harm to a mangrove.

PAGEAll right. Mr. Stevens, thank you very much for giving us a call.

STEVENSI thank you.

PAGEWe've had lots of interest in how you can make sure that the food that you're buying is gotten in a sustainable way. Lourdes from Miami, Fla. is calling on that. Lourdes, thanks for giving us a call.

LOURDESHi. Thank you. Thank you for putting me on. I just wanted to make a comment. You know I work in food service and of course I sell a lot of shrimp. One of the ways a consumer can tell if it's a farm-raised or wild caught is by the species. The black tiger shrimp is the shrimp that is farm-raised, you know, usually in Asia or Thailand. And I just wanted to make a note, you know, for me selling wild-caught shrimp, whites or pinks from the Gulf or South America, it's a very tough thing to do because of pricing. You know, black tigers that are imported from Asia tend to be significantly lower in price. You know, the quality of the product, in my opinion, is not as good as the pinks or whites, but selling it to a restaurant that's, you know, gonna offer it as a meal, sometimes you can't justify the $3 a pound difference.

LOURDESA few years ago we actually had some containers that were held back because USDA tested some of the shrimp that was coming into the U.S. from Thailand. And the testing that they did on the shrimp, it was toxic. You know, the chemicals that they use, you know, they're raised in brackish water. I've done taste tests many times side-by-side and hands down the domestic-caught shrimp tastes what a shrimp should actually taste like. So for the consumer to want to know what the difference is, black tigers are all farm-raised.

PAGEAll right.

LOURDESThat was the point I wanted to make.

PAGEAll right. Thanks so much for offering us your expertise. You know, we've also gotten messages that there's a group, The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, that has a website that has recommendations for ocean-friendly seafood. That's at seafoodwatch.org. And we've put a link to that on our website at drshow.org. And a mobile-friendly guide at fishphone.org, we're linking to that, too, on our website.

PAGELet's go to Zack. Zack is calling us from Farmington, Mo. Hi, Zack.

ZACKHello.

PAGEYou're on the air. Please go ahead.

ZACKYes. In graduate school, I went to the College of William and Mary. And in my GIS class we worked on a project involving mangrove swamps in Ecuador. And we mapped out the shrimp farms over a period of decades, starting back in the '50s, using black and white topographic maps and going all the way, using land sat. data, all the way up into the early '90s, if I remember correctly. And we tracked that shrimp farming and the growth of it or decline of it based off of foreign aid.

ZACKWe had a lot of foreign aid data that we were using from Ecuador, through the IMF, the United States and from several other countries that were involved with it. And we were trying to make a correlation. It was very preliminary because it was a project that the professor wanted to work on over a period of years 'cause he had done all sorts of GIS work for many years in Ecuador. And we found out that, you know, as the foreign aid actually increased inside the country, the number of shrimp farms started to increase.

ZACKAnd we didn't have, you know, enough time in the semester to really comb through the data to really check out the facts, but it had a very interesting correlation that, you know, other countries wanted shrimp so they donated money to Ecuador to try to increase the number of shrimp farms there. Or, at least, maybe that's where the country pushed the money towards because it was very profitable for them.

PAGEInteresting. You said this was your GIS course. What does that mean?

ZACKYes. It was a geographic information systems course that I took at College of William and Mary. They should have some of that information up on their website. And I don't remember the exact specifics of it because it was, I think, the first year that we had done it. And I think subsequent years have expanded on the research or at least done additional research on it.

PAGEAll right. Zack, thanks very much for your call.

WARNEYeah, when you look at those comparative maps between say 20 years ago and today, it's a disturbing comparison of a lot of green areas back in the '70s and '80s suddenly becoming a lot of red areas on the map where the mangroves have been lost. But just coming back to the previous caller's comment about price, this is a key thing. The question is if we insist on having all-you-can-eat shrimp at a seafood restaurant for 15 bucks or something like that, we have to realize that there's an environmental subsidy going into that, a huge subsidy.

WARNEThere are some experts who do this ecological economics, who begin to look at what are the subsidies that are going into that. And they've estimated that a 250 acre shrimp farm incurs a million dollar, annual million dollar environmental cost. Another little calculation I did in the book was to look at the kind -- if you were to have a sustainable shrimp operation, the level of environmental services in cleaning the water, in providing the shrimp fry, in dealing with the waste products, in so many ways would end up making shrimp cost about $1500 a pound.

WARNENow, I think the point is that many people are beginning to think about what are the subsidies, what are the externalities that are going into food. We don’t want these hidden costs. We need to be aware of what they are, who's paying the bill. And it's partly the environment, but I also argue that it's partly a lot of people, a lot of coastal poor who end up paying the price so that we can enjoy luxury seafood.

PAGEYou talked about the workers who get honey off Bangladesh from a mangrove forest. You also wrote about in Ecuador about cockle gatherers.

WARNEYeah.

PAGEWho are they? What do they do?

WARNEWell, it turns out there's a little clam that -- well, there's two or three little clams that live in amongst the roots of mangrove forests. And a group of people, collectors known as concheros, the cockle gatherers or the concher gatherers who go in. And they're mostly women and they often have their children with them. And they go in everyday at low tide. They walk through the scaffold of mangrove roots. it's a very dense forest. The easiest way to get through a mangrove forest is often to climb 10 or 15 feet above the soil so you can get out of the range of the labyrinth of mangrove roots.

WARNESo they climb through the forest and they descend to an open area and begin to gather cockles. And that's, for these women, the sole form of livelihood or the sole cash economy that they can have. And there is, amongst both sides of Latin America, both the Atlantic and the Caribbean side, there's another group of people, the mangrove crab collectors who plunge their arms full length. They lie on the mud and reach into the burrows of these enormous crabs with very large pincers. And that's their method of gaining a livelihood. And it's closely controlled, they never take the females and they have certain size limits and so forth. And this is a very indigenous and sustainable livelihood, but as I argue, for large parts of the developing world that's no longer available. It's been displaced and these people have been marginalized.

PAGEI'm Susan Page. And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We're taking your calls, 1-800-433-8850. Let's take Cody. He's been patient, has held on. Cody's calling us from the Keys in Florida. Boy, you must have a lot of mangroves around your neighborhood.

CODYYes. We actually live in the mangroves down here. Our mangroves, we don't consider them swamps as much as we consider them more of an estuary. We have an awful amount of Audubon things that we've been doing here over the years. We have an extreme amount of regulation. You can't even build a house a certain way without it. I guess I would have to say that this would be a good place to visit of an environment that is being sustained with the mangrove and we're working our best we can within the realms of reality to maintain this.

CODYI used to be a shrimper. There was a couple shrimp farms that we did have down here, but they've fallen by the wayside. They were not productive enough. It turned out that it was easier to go around and rake the turtle grass for the shrimp that we have, the pink gold, as we called it down here. We have a substantial amount of the animals that you have discussed already in Malaysia and South America, the jaguarondi, which is the Florida panther. We have the Florida otters down here, saltwater crocodiles and Caymans, very surprising.

CODYNow, a lot of the problems that we're having recently is exotic animals and plants that are coming in here and an extreme amount of development with these houses that are going up with the real estate. It's kind of changed the water from blue to green in a little ways, but I have to say our biggest fear right now is that Cuba's about to do some off-shore oil drilling. So I will say that I'm -- after listening for awhile I'm rather proud that the management and custodianship that we've done down here in the Florida Keys. And I think it's a place to visit.

CODYWe do a ton of eco-tours down here so we can educate people on the mangrove and how they are very beneficial to all the things that you're talking about, including agriculture. We also have a substantial amount of mangrove islands that are resting on top of cap rock shelves. So there's not a lot of the sulphurous mud that you're discussing, but I will admit that the mangrove honey that we get down here is pretty spectacular.

PAGEAnd no tigers, I assume. All right, Cody. Thanks for very much for your call.

WARNEYes. He's right. And in many developed countries the level of protection of mangroves exceeds that in the developing world and is great. I spent time in the Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge. And that is a wonderful mangrove habitat. You can do canoe or kayak tours for several days and camp on a little hammock with mangroves all around. And that would be a great way for people in the U.S. to gain an experience of your own mangrove forests.

WARNEAnd the previous caller mentioned Costa Rica. Australia has huge areas of mangroves. If you want to see saltwater crocodiles that's the place to go and you can do tours in the Daintree through wonderful mangrove areas. So, yes, people are becoming aware of the multiple benefits and sheer intrinsic value of these wilderness places. We've got to stop thinking of forests as a resource. And start thinking of them as wild places to which we can connect and which we need to connect because we're just part of nature, just like the mangroves are.

PAGEAnd one of the encouraging things in your book is you talk about the fact that mangrove forests that have been lost can be restored and rebuilt.

WARNEThat's right. And when you walk through an area and you think, you know, five years ago this wasn't here and you look at the way nature floods back, I mean we used to have that old phrase in high school, nature abhors a vacuum. And you begin to plant the mangroves again and it's extraordinary how much life, how quickly the life comes back. And we just need more of it. As I said, the rate of mangrove replanting is way less than the rate of mangrove loss, taken as a global picture.

WARNEWe should be supporting organizations. And there are -- the Mangrove Action Project is a great U.S. organization that is involved in that process.

PAGEKennedy Warne, author of "Let Them Eat Shrimp". Thank you so much for being with us this hour.

WARNEThanks, Susan.

PAGEI'm Susan Page, of USA Today, sitting in for Diane Rehm. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER"The Diane Rehm Show" is produced by Sandra Pinkard, Nancy Robertson, Denise Couture, Monique Nazareth, Nikki Jecks, Susan Nabors and Lisa Dunn. And the engineer is Tobey Schreiner. A.C. Valdez answers the phones. Visit drshow.org for audio archives, transcripts, podcasts and CD sales. Call 202-885-1200 for more information. Our email address is drshow@wamu.org and we're on Facebook and Twitter.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.