Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

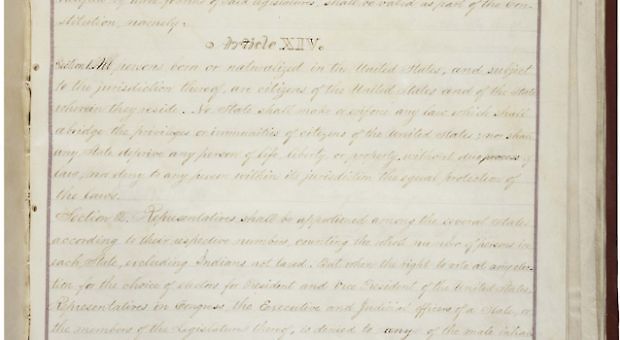

The Fifth Amendment was added to the United States Constitution in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights. It includes the right to a grand jury trial, the right to not be tried twice for the same crime, and the well-known “right to remain silent.” But the Fifth Amendment also bars the government from taking private property without fair payment, and only for the “public good.” Today, as part of our ongoing Constitution Today series, we examine the origins and evolution of the 5th Amendment, and how the case of the “Little Pink House” altered the Eminent Domain protection forever.

Most of us know the Fifth Amendment for its famous right to remain silent, but the Constitution also guarantees property owners fair payment for land the government takes to build highways, protect natural resources, and even to renew urban areas. As part of our Constitution Today series, we move beyond “pleading the Fifth” to examine the delicate balance of the imminent domain clause.

What Protections Does The Fifth Amendment Offer?

Rosen outlined the main tenants of the Fifth Amendment. First, if you’re going to be indicted for capital and specific offenses, first you have to be indicted by a grand jury. It also outlines the “Double Jeopardy” clause, which says you can’t be convicted or acquitted of a crime and then tried for that crime again. There’s the “self incrimination” clause which gives us the Miranda warnings and the ability not to be forced to testify in court in ways that could hurt you in a future case. There’s the due process clause, which ensures no one shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law. And finally, there’s the protection against private property being taken for public use without just compensation.

When And Why Was It Added To The Constitution?

The Fifth Amendment wasn’t part of the original Constitution. James Madison was strongly against the idea of a Bill of Rights, but George Mason strongly favored it from the beginning. Quinn believes that chief among his concerns was probably the fear that some right would be left out if we tried to list them, and that it might also create the impression that our rights come from the government when the political theory of the country is based on the idea that we have natural rights. But Madison

changed his mind, and pledged to introduce the Bill of Rights in the first Congress once the Constitution was ratified.

Limitations To The Amendment

Diane asked the guests if they think the Fifth Amendment protections have been limited too much in the hundreds of years since its creation. Wiener doesn’t think so. For instance, double jeopardy can’t be limited too much. But concerning the eminent domain clause, complications have arisen, such as when “just compensation” isn’t desired by a private citizen. “For the property owner, it’s not about money,” he said. “It’s about the marks on the inside of your closet when you saw your child at age eight, at age twelve, at age eighteen,” he said. Landmark cases involving this clause have been centered on whether or not, and when, the regulation goes too far. “Essentially the Supreme Court has said that when you completely destroy the value of a property making it impossible for a landowner to build at all, then compensation is necessary,” Rosen said.

Caller Question On Re-purposing Land

A caller from upstate New York wondered if land that was taken from his grandfather in the 1950s under public domain for a public school and is now slated to be used as a daycare or other for-profit business. He wondered if landowners have any recourse given the change of purpose for the land. Weiner said there was a case to be made and that there are precedents for owners receiving compensation when public use of private land ceases.

You can read the [full transcript here]

(https://dianerehm.org/shows/2012-01-30/constitution-today-fifth-amendment/transcript).

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. Most of us know the Fifth Amendment for its famous right to remain silent, but the Constitution also guarantees property owners fair payment for land the government takes to build highways, protect natural resources or even to renew urban areas.

MS. DIANE REHMAs part of our Constitution Today series, we move beyond pleading the Fifth to examine the delicate balance of the imminent domain clause. Joining me in the studio, Jeffrey Rosen of the George Washington University's School of Law, Michael Quinn of James Madison's Montpelier, and Lewis Wiener of Sutherland and Asbill. And throughout the hour, we'll take your calls. I hope you'll join us by phone, by email, a posting on Facebook or send us a Tweet. And good morning to all of you.

ALLGood morning.

REHMGood to see you all. Now, Jeffrey Rosen, let me start with you. Briefly, give us a sense of the protections that the Fifth Amendment affords to all Americans.

MR. JEFFREY ROSENThere are at least five separate protections in the Fifth Amendment. There's an awful lot in it which makes it so important. So I'll just read it and we'll try to separate them into five separate clauses.

REHMGood.

ROSENSo here's how it begins. Uh, first, we have the grand jury clause. It says, "no person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces or in the militia when in actual service in times of war or public danger." So that's the clause that says that if you're to be indicted for the capital and specific offenses, you have to be indicted by a grand jury.

ROSENNext, we have the double jeopardy clause. It says, "nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb." You can't be convicted of a crime or acquitted of a crime and then tried for the precise same crime.

ROSENNext, we have the self incrimination clause. Nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself. That's what gives us the Miranda warnings and the ability not to be forced to testify in ways that could hurt you in a future criminal case.

ROSENNow we have the due process clause, which is, in some ways, the most important of them all. "Nor be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law." That's the clause in which the Supreme Court has discovered economic liberties, the right to choose abortion, so many of our most controversial questions are litigated through that clause.

ROSENAnd then, finally, we have the clause we're gonna be focusing a bit on. "Nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation." And the question of what is public use and how much you have to be compensated when the government seizes your property is something I know we're gonna be talking a lot about.

REHMNow, turning to you Michael Quinn, give us a little of the background on the Fifth Amendment. When and why was it added to the Constitution?

MR. MICHAEL QUINNWell, you're right, Diane. It was added. It was not part of the original Constitution that emerged from the Constitutional Convention. And Madison was one of the people who was really against the idea of a Bill of Rights. George Mason, from the beginning, thought it was necessary, but Madison argued that, firstly, that it was unnecessary because the Constitution was granting only specific powers and that none of those powers enabled the federal government to invade the rights of individuals.

MR. MICHAEL QUINNHe had other concerns, as well. Probably chief among them was his concern that we might omit some rights if we tried to list them. And it might create the sense that our rights come from government, when, in fact, the political theory of America is based on the idea we have natural rights that preexist government.

MR. MICHAEL QUINNWell, Madison ultimately changed his mind, listening to George Mason, Thomas Jefferson and also to John Leland, a very influential Baptist minister in Virginia, who warned him that Virginia would not ratify unless there was a Bill of Rights. And Madison pledged himself to introduce a Bill of Rights in the first Congress if the Constitution was ratified.

REHMWasn't there also a farmer, John Lilburne -- actually he was an Englishman, first a Puritan, but later a Quaker.

QUINNYeah.

REHMTell me about him.

QUINNWell, that was much earlier. About a century earlier. And it was actually a case -- wait a second. I think I've got that -- I'm confusing it with another case.

ROSENThe Puritan dissenter who wanted to import …

QUINNThe Puritan dissenter.

ROSEN…pamphlets into Britain, which were heretical. And he was called before the Star Chamber and forced to swear an oath ex officio. Basically, he swore to answer any question that was put to him without knowing what it will be on penalty of perjury. The framers considered this a form of triple torture. It was the cruel trilemma because he could tell the truth, confess his heresy and be condemned for religious heresy, he could refuse to answer and be held of contempt of court or he could lie. And for the Puritans, lying under oath meant eternal damnation. This was a very serious thing in an age that took oaths seriously.

ROSENAnd because it was considered unfair to subject people to that cruel trilemma, the framers of the Constitution guaranteed the right that Lilburne had asserted nemo tenetur, no man is bound to accuse himself. And that's what ended up in the Fifth Amendment.

REHMAnd Lewis Wiener, have Fifth Amendment protections been limited too much?

MR. LEWIS WIENERLimited in the sense of, I think that the Fifth Amendment protections are now under a Kelo light. And once they are brought to the forefront, of course, is going to be argument they are subject to undue limitation. My personal opinion is the answer is no, that the Fifth Amendment affords citizens the right as they've been outlined.

MR. LEWIS WIENERYou have a right against double jeopardy. That can't be limited too much. You have a right against self incrimination. That can't be limited too much. It is a right that's afforded to you by the Constitution. And to that extent, it is inalienable.

REHMAn awful lot of people you hear take the Fifth and those who are listening or watching on television assume that that person is guilty because he or she is taking the Fifth. Lewis?

WIENERAnd that is an assumption that is invalid in criminal prosecutions, but would be valid -- silence can be considered an admission in civil proceedings. And there's a critical distinction between the two. You have a right not to self incriminate in the criminal context and no adverse inference can be drawn from that. In the civil context, the presumption is different.

REHMBut there is a case that Congress is investigating, Operation Fast and Furious. And you had former U.S. Attorney Patrick Cunningham pleading the Fifth. What was all that about?

WIENERThat stems from an operation in Arizona called Fast and Furious, relating to the collection of guns. And it went wrong. I don't know where it went wrong. I don't know how it went wrong, but there were allegations that misinformation was provided in the conduct of the operation. The prosecutor was subpoenaed and refused to testify.

WIENERNow, I will say that if the underpinnings of that operation were the subject of a civil subpoena, the government itself would object to the prosecutor testifying. They would assert deliberative process privilege. They would say that how that operation came about, the decision making that went into it would be privileged, but ironically, here's the government subpoenaing that information and now holding up to the Kelo light and objecting to the Constitutional assertion of the self incrimination.

REHMJeffrey?

ROSENAnd of course, Patrick Cunningham has an absolute right to assert the fifth because any time you fear in any proceeding, civil or criminal, that your words might be used against you in a future criminal proceeding, you are absolutely entitled to take the fifth without being second guessed.

REHMAnd talk about the double jeopardy clause, Michael. Why did the framers think that that was so important?

QUINNWell, that concept goes back in law almost a millennia. I mean, you could even find Demosthenes talking about it. And it was well established in English law that government can't keep trying again and again to convict you. They have one chance to try. And that was a principle that was established in English law and it actually existed in some of the state constitutions that Madison looked at in putting together the Bill of Rights.

REHMThere is some pretty famous cases in double jeopardy. Jeffrey, Jack McCall, the guy who murdered Wild Bill Hickok, for example.

ROSENAbsolutely right. And he committed his murder on Indian territory so he's tried on Indian territory.

REHMOkay.

ROSENAnd was acquitted there. And then, he was retried by the U.S. government and the finding was that because the initial trial was not within the jurisdiction of the United States, the double jeopardy clause did not apply. There are lots of other famous cases. We know, of course, of O.J. Simpson, who is acquitted in a criminal case and then tried and punished civilly and that's because the double jeopardy clause prohibits two criminal prosecutions, but does not bar a subsequent civil prosecution.

REHMAnd does that make sense?

QUINNWell, it certainly makes sense from the government point of view in terms of -- because the government resources are so enormous they could really harass and persecute someone simply by again and again bringing them to trial. So it was a very important right to establish in the Bill of Rights.

REHMOf course, you've got O.J. Simpson in a jail now on totally different charges.

ROSENThat's right. And I think if the concern of the double jeopardy clause is to limit the power of government, it shouldn't be construed to limit the availability of fellow citizens to seek legitimate damages for wrongs that they've inflicted on each other. So you can be locked up for civil offences, but as long as it's not the government that's bringing the charge, that's not considered double jeopardy.

REHMJeffrey Rosen, he's professor at the George Washington University Law School and legal affairs editor at The New Republic. As we talk about elements of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, I'll look forward to hearing your questions and comments, 800-433-8850.

REHMAnd in this hour we're continuing our series on the Constitution Today. We're talking about the Fifth Amendment, which as you heard earlier includes many, many clauses in regard to self-incrimination, trial by a grand jury, double jeopardy or taking of property unfairly without due compensation. Here in the studio Lewis Wiener. He's a partner in Sutherland, Asbill & Brennan, a former trial lawyer at the U.S. Department of Justice where he was director of the Court of Federal Claims docket.

REHMAlso here, Michael Quinn, president and executive director of James Madison's Montpelier and Jeffrey Rosen, professor of law at George Washington University. Lew Wiener, talk about the questions regarding eminent domain. What constitutional rights does the eminent domain clause give to Americans?

WIENERWell, let's look at the words of the Fifth Amendment. Nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. There it is. Private property may not be taken for public use without the payment of just compensation.

REHMBut suppose you've got a situation where private compensation or just compensation is not desired?

WIENERWhat you're really getting at cuts to the core of the Fifth Amendment controversy. For the property owner it's not about money. It's about the marks on the inside of your closet when you saw your child at age eight, at age twelve, at age eighteen. It's about the Thanksgiving dinners you had in your home, the birthday celebrations. To the government it's about just compensation. It's your proposed use of the property violates section XYZ/123. And the property owner doesn't really care about that.

REHMGive me some examples of early cases involving eminent domain, Jeffrey Rosen.

ROSENSome of the earliest ones were written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. There was a case involving mining authority. And Justice Holmes said -- and rifling through my case book here, I was glad to reread these -- but this is the Pennsylvania Coal and Mahon Case in 1922. And Holmes allows this Pennsylvania Coal Company to mine under property. But he says that in this case it goes too far because it made the mining commercially impracticable.

ROSENAnd this was his famous rule. The general rule is that while property may be regulated to a certain extent, if the regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking. That phrase has prompted much of the controversy over the next 100 years. Who's to say whether something goes too far? Justice Lewis Brandeis, my hero, in that case wrote a descent where he said it's not up to judges to make essentially economic decisions about what goes too far. If there's an injustice it should be remedied by the legislature.

ROSENAnd that's why all of the great controversies of the 20th century involved this basic question of who should decide when the regulation goes too far. And essentially the Supreme Court has said, when you completely destroy the value of a property making it impossible, for example, for a landowner to not build at all then compensation is necessary.

ROSENBut when you merely diminish the value of the property -- for example, the famous Grand Central landmark case where Penn Central, which owned the beautiful Grand Central terminal in New York, wanted to build a 55-story office building above Grand Central, and the Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Brennan, said that the New York City Landmarks Commission could prohibit them from building that tower. It's true, it diminished the value of the property, but it didn't prevent them from running a railroad, which they've done before. And essentially, regulatory takings are permissible if they serve the public interest of the community as well.

REHMMichael.

QUINNYou've really got two strands of legal authority coming together. One is just a straight taking by the government. And that goes back to the Magna Carta when the nobles are trying to protect themselves from the king. At the same time, there's a recognition that, at times, the government does have the right. There's a greater good to be served. That's how our railroads were built and our highway systems.

QUINNThe legal constraints on that were first that it has to be lawful. There has to be some legal process. And finally, really in the late 18th century, Massachusetts among the first, payment of just compensation. Prior to that, there'd been no payment whatsoever. The other train of thought is -- the other legal train really is the idea of government regulating your use. And that has existed in law a very long time.

QUINNI mean, even back in colonial times you couldn't start slaughtering animals and tanning hides in a residential area. There were nuisance laws, public benefit laws that prohibited that. And that was really transformed into zoning in the early 20th century. And then we're now finding that zoning starts to look like a taking under certain circumstances, the kind of cases that Jeffrey was just citing.

REHMLew.

WIENERI think to put a finer point on it there are two strands. One is the physical taking. You own a piece of property, the government wants to expand a road, your property is right where that road's going to go. The government comes in and says, we are taking your property. We are physically acquiring your property to build the road, to build the court, to put in a prison, a school, etcetera.

WIENERThe other strand is the regulatory taking. The government doesn't actually physically encroach upon the property but by operation of regulation they've restricted your use. And the question then becomes when is the restriction too much. When does it cross the line where you can no longer use your property as you intended? And therefore the government has to pay just compensation. And that gets to the Penn Central case and the three-part test the Supreme Court announced therein.

ROSENAnd then within the regulatory takings category, we have a further controversy of course, and that's what permissible uses can the government enlist private companies to encourage? So the most controversial takings case of recent years, the 2005 Kelo case involved just that. And of course we want to talk about that. That was the case where the City of New London wants to seize a woman's house through the power of eminent domain, allow it to be developed by a private corporation, the Pfizer Corporation, which has a plant right downtown, in the hope that this will invigorate the area.

ROSENShe said that this is not a public use, it's a private use. You're basically giving the power to this private company to seize my home and develop it. In the past courts had said you could redevelop to eliminate economic blight, but the idea that you could seize property for economic development was controversial. The idea that the city as a whole would benefit if the downtown area were improved hadn't been conclusively established.

ROSENBut the Supreme Court in a very controversial five to four decision written by Justice John Paul Stevens sided with the City of New London, allowed the property to be seized and provoked a firestorm of a political reaction. Forty-two states since 2007 have passed laws and proposed constitutional amendments repudiating part of Kelo and trying to redefine blight more narrowly or prohibit this sort of redevelopment for economic benefit. So this remains one of the liveliest and most contested questions of (word?) today.

REHMAnd that was the subject of the recent book "The Little Pink House," which was really quite a story. So where does that take us then?

ROSENWell, at the moment Kelo remains the law of the land. Lots of states have limited its impact. Pennsylvania, for example, which I gather has more takings than any other state for private purposes, has defined economic blight more narrowly and has also eliminated the circumstances in which you can do this economic redevelopment takings. Although the law does not apply in Pittsburgh and in Philadelphia, the biggest parts of the state.

REHMWhy?

ROSENI think the thought there was that there was so much urban blight that you actually needed this broad power. But -- and there are constitutional amendments pending in Virginia and other places. So -- and it's also not at all clear that the current supreme court would view the case in exactly the way that the court did just a few years ago.

REHMYou know, it's interesting long, long ago our first house was right on a small lane then called River Road. And then they decided to widen River Road. And they sent us a letter saying we're taking part of your land and using it to widen the road. And I said, hey, wait a minute. I am going to have my property measured so I know exactly where my land ends. And if you're going to take part of my land you're going to pay me for it, which they ultimately had to do. Lew.

WIENERDiane, it gets back to the point I made earlier about the emotional impact of this. If you think about it we have a constitutional guaranteed right to vote. We have a right of free speech. We have a right of freedom of religion. In order for us to lose those rights you've got to do something wrong. And you're afforded your due process rights to defend yourself. You can lose your property without doing anything wrong. You do everything right. You work hard, you raise your children, you invest, you buy a house, and the government can come and take it without you doing anything wrong. How offensive that is to people.

QUINNBut at the same time, and I believe strongly in the rights, the recognition is that there are times when there is a public need, whether it's building that road...

REHMThat road.

QUINNAnd we would not have a railroad system or a highway system if the government did not have that right. So the point of the amendment is to place constraints to make sure that that right that Lew just described isn't invaded without real reason and without you being compensated.

REHMDo we know how often that right of eminent domain is actually challenged?

ROSENI found -- there's some interesting articles about the effect of the Kelo case and I'm looking for the exact numbers, but I think in Pennsylvania alone, since the decision, there were more than 2,000 seizures in which private companies played a role. That was the state that had more seizures than any other, even in California. The others had several hundred a year, so this happens quite a lot.

REHMI don't understand Pennsylvania. What's going on in Pennsylvania?

ROSENIt was litigated from the beginning. I also found, you know, we're very interested in Pennsylvania law here. And there was a 1913 Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision that did impose limitations on the ability of a mining company to seize land in order to build a road to create a way of access. But that is different from decisions that are trying to extract natural gas from a property 'cause that's considered to be in the public interest, so essentially these regulatory takings for natural gas extraction have not been substantially regulated in the wake of Kelo.

ROSENThere's a movement in the west to begin to pass statutes that would regulate that. But right now, the gas company using a statute with the authorization of the government may, in fact, be able to seize land and extract minerals 'cause that's considered to be in the public interest.

WIENERBut I think that we have to look at not only -- it's not just a numerical issue, how many challenges are there, but it's what's being challenged. Pre-Kelo -- and I'm talking about this when I was with the United States and defending eminent domain cases, you would see very few cases where they challenged the public use requirement. Now more cases, as a result of Kelo...

REHMInteresting.

WIENER...again, nor shall private property be taken for public use. And that's something that Kelo really shown a light on. It's public use, yet when you read the decision you see that what the court was focusing on wasn't public use in the narrow sense, a public use, but public purpose, public benefit.

WIENERAnd if there is something that the practitioners find particularly compelling about Kelo, it's the expansion -- and arguably the expansion of public use to public purpose and public benefit because public purpose and public benefit is far broader than public use.

REHMLewis Wiener and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We have many callers. Let's open the phones. First to Lansing, Mich. Good morning, Chris, you're on the air.

CHRISGood morning. Great show. I listen all the time, Diane. I wanted to call today and ask what -- talking about eminent domain and the government seizing property, what this amendment says about what I see as a disturbing increase in the use of civil asset forfeiture to take people's property in criminal -- they've not been found of any wrong doing. And I can take my answer off the air.

WIENERThere is a distinction between a government taking of property for public use and a civil forfeiture action where you are forfeiting your property because of an alleged violation of some statute or other law. Again, there are restrictions on use of property. There are certain times where property can be taken in the sense of you lose possession but not taken in the context of the Fifth Amendment because it's not being taken for public use.

REHMI see. All right. To Saint Augustine, Fla. Good morning, Brian.

BRIANGood morning, Diane. For your esteemed panel, I'd like to ask two quick questions and I'll take my answer off the air as well.

REHMSure.

BRIANI'd really like to know why self-incrimination is protected in criminal trials, but not in civil trials. I've never understood that distinction. And two, why are some schools given the right of eminent domain, that there's a current debate going on in the City of Saint Augustine right now. And that might help me understand how that all began. Thank you.

ROSENOn the civil criminal distinction, I think it has to do with the remarkable centrality of oaths to the history of the Fifth Amendment. It wasn't a general right not to get yourself into trouble, but the right not to be put under oath and face the risk of eternal damnation as a result that led to the Fifth Amendment. And that's why for much of American history defendants were not even allowed to be interrogated under oath. That didn't end until the late 19th, early 20th century. And I think because civil cases relied less heavily on interrogations under oath there was less of a concern about self-incrimination.

QUINNAnd you're also just seeing in government action a transition from conviction coming from inquiry, or from which we get the word inquisition to evidence. So it really is relying -- forcing the government to rely more and more on hard objective evidence rather than just what words a person utters or is coerced to utter.

REHMAnd what about eminent domain as far as schools are concerned?

WIENERWell, again, arguably, there's no clearer -- or one of the few clearer examples of private property being taken for public use in building schools. And some school districts by legislative fiat have been given the right to exercise the right of eminent domain. But that's where you get legislative as opposed to judicial.

REHMBut if somebody's house is right where the school district, the state or whatever decides they're going to build the school, what recourse beyond financial remuneration does the homeowner have?

WIENERWell, before you get to that issue of just compensation, financial remuneration, you can propose alternative use. There's another way for you to do this so that it's not going to impact me, the homeowner. And it's not going to be as costly for you. And homeowners have -- we've represented homeowners where we've gone back to the condemning agency and said, there's another way for you to do this. Consider that.

REHMAll right. And we'll consider a lot more about the Fifth Amendment as we continue our conversation after a short break.

REHMAnd welcome back. Lots of our listeners want to know how "The Little Pink House" issue was finally resolved, Jeffrey.

ROSENSo what happened is that this whole project ended up failing. More than $80 million in taxpayer money was spent, but there ended up being no new construction whatsoever. The neighborhood is a barren field. In 2009 Pfizer, which was supposed to be the keystone of the economic development, announced that it was leaving New London for good as soon as its tax break expired. As for the little pink house, it was moved to a new location. And I'm reading from the Institute for Justice site, but you can visit this house at its new location in downtown New London, 36 Franklin Street at the intersection of Franklin and Cottage Streets. So it's become a monument to injustice for many people.

REHMAll right. To Syracuse, N.Y. Good morning, Jim.

JIMGood morning, Diane. I've got a question for your panel. I have -- we live in a rural community here in upstate New York and they're trying to close one of the schools, the elementary school, and everybody's in an uproar of course. But my question in regard to the public domain, they took the land from my grandfather back in the '50s for public domain for use as a school. They want to reconfigure the grades and make this school -- they want to rent it out for a daycare, a day-hab or a rehab or whatever use they want to use for it.

JIMAnd I'm curious if I have any recourse given the fact that it was taken under public domain for use as a school and now they want to rent it out.

REHMLew.

WIENERPerhaps. There are a line of cases, the rails to trails cases, where property was taken by railroads for use as a railroad right-of-way. The railways later abandoned the right-of-way and the property owners sued to get the property back. The success of those cases, it often turns on what were the conditions of the original deed. When the property was taken what did the railroad take?

REHMAnd what did the owner receive in compensation?

WIENERThat's correct, that's correct. And arguments have been made that in fact once the original purpose, the public use purpose no longer exists that the property owner is entitled to get the property back. The cases are, of course, all over the board.

REHMMixed, yeah.

WIENERBut there is at least an argument to be made depending on what was taken, the nature of the interest that was taken and it does warrant some further probing.

REHMJim, do you still have your grandfather's deed to that property?

JIMYes, ironically. Yes, we do have the original (unintelligible) .

REHMWhat do you think, Jeffrey Rosen?

ROSENThat should help. It sounds like we've got someone ready to represent you right now.

REHMWell, it does seem as though if the original purpose has now changed dramatically that Jim has at least some questions to raise. Wouldn't you agree?

WIENERThat's right.

REHMGood luck to you, Jim. Thanks for calling. Let's go to Baltimore, Md. Good morning, Bill.

BILLGood morning. In Baltimore we've got a thing up there called receivership. What they're trying to do is take my house away by saying it's not up to code and put it up for auction without giving me anything. It's mainly because I've got a $40,000 house in a neighborhood full of $150,000 houses and don't owe any money on it or anything but taxes. And one neighbor's been trying to buy my property for years and has been complaining about the condition of the house. And now they're trying to steal it from me.

REHMNow, does that fall under eminent domain or the Fifth Amendment?

WIENERI don't know enough about it to be able to say definitively but again we get into areas like zoning where if your property falls below certain community standards, the government is not powerless in terms of enforcing those community standards.

REHMThat's interesting. All right, Bill. Sorry, can't give you more of an answer than that. Let's go now to Kokomo, Ind. Hi there, Roger. Go right ahead.

ROGERGood morning. Thanks for taking my call. I just had a question about when the government rewrites the floodplain and they put your home in that that would devalue your property and restrict you. Would that fall under the regulatory taking in the restrictions of your property?

REHMJeffrey.

ROSENThe general rule is that as long as it doesn't completely wipe out your economic value, it doesn't allow you the ability to develop a parcel at all, even though everyone else had developed it, or it doesn't deprive you of all economic value, then the mere fact that it's worth less than it was before the regulation is okay.

QUINNThis comes out of zoning rather than eminent domain.

WIENERA mere diminution in value does not necessarily trigger the takings clause.

REHMGotcha.

WIENERThe government is not the insurer of last resort.

REHMAll right. To North Port, Mich. Good morning, Herb.

HERBGood morning, Diane and panel. I would like to present my case here to see what the panel thinks about the process involved. My home is located on Grand Traverse Bay. It's an arm off the Great Lakes. And being on the bay, the property is valued at $2,000 minimum. And we had a sewer project here locally and initially the run off the sewer avoided our property. But because the governing authority thought that they could save some money they ran the line through our property between our home and the bay.

HERBWe had the capability of having two building sites between our home and the bay. And that sewer line going through there eliminated any possibility on that. When the community -- or when the community leaders condemned our property for the easement they offered us $825 for that easement for the loss of value. An appraisal came in at $104,000. We took it to court and spent $12,000 trying to right things. We finally ended up getting about one-third of that -- the value of the land minus the $12,000 we had to spend in legal fees.

HERBNow our case was heard by a local judge whose probably only experience was dealing with DUI cases and (unintelligible) assaults and things like that. So where is my option -- where could we have gone from there in order to get some kind of -- in order to right this wrong decision of a local judge?

ROSENWell, the first question of course is whether or not the fact that the value of the property went down would be covered by the takings clause at all for the reasons we've just been describing. But if it were found to be a taking you can litigate the question of fair market value. The government has to pay fair market value to the owner. It can't just jack up, you know, the price exorbitantly. And then there's a whole series of standards for litigating that. So I think that that would be the most promising way to go.

WIENERAnd the next avenue, assuming that you're not time barred, is to appeal. You have the appellate right. If this was a trial-level court you take it to the next level in the appellate process.

REHMHe's going to have to spend more money to do that.

WIENERThat's correct. And -- but one element of just compensation includes the return of attorney's fees, expert costs. But that can be limited by statute and does vary state by state.

REHMIs -- are the numbers of cases of eminent domain takings by the government or local authorities on the increase?

QUINNWell, you know, you would expect it to be, Diane. I mean, when you think of the early days of this nation it was a population of three million. It's now well over 300 million. And the whole concept of public good is changing too. I mean, one caller talked about he's in a floodplain or a coastal zone. I mean, these are concepts that just didn't exist at the time. When you've got three million people spread out across the Eastern seaboard, you know, farmers planting their field don't really cause environmental impacts. When you've got, you know, tens of millions of farmers fertilizing their fields the runoff does have an impact.

REHMAll right. To Boon, N.C. Good morning, Casey.

CASEYHi, good morning.

REHMGood morning, sir. Casey.

CASEYI wanted to ask a question -- I wanted to ask a question. If a highway through -- they're going to take your land and take your house, whatever it may be, is there a standard that they have for determining what your (unintelligible) will be? Like (unintelligible) about local tax, how you -- and whatever. And I'll take my answer off the air.

REHMAll right, thanks. Lew.

WIENERWell, again the measure is just compensation and that's a question of valuation. What usually happens is the government has an appraiser, the private property owner has an appraiser and it becomes a question of which appraisal does the court believe is more accurate based on a number of what are admittedly subjective factors.

REHMTo South Port, Conn. Joanne, go right ahead.

JOANNEThank you. I'd like to ask, now do the people in New London have any recourse? Because there seems to be an element of fraud here in that they're not using the land for what they originally sought it for. And if, you know, they're leaving after their ten years and they're leaving the, I guess an empty lot, but also if we don't do something about this does it set a precedent to say another company won't come and do the same?

WIENERWell, I don't think it's fair to say there was fraud. They were mistaken and it's okay to be mistaken. It's okay to go in with all good design but for whatever reason it didn't pan out. The fact is the property owners were paid. And in return for the payment the government received likely the deeds to those properties. The government now owns them. And if there's anyone that I would think about be upset from a strictly economic perspective it would be the government.

ROSENThere's also a question about who's best able to protect rights. Is it the courts or citizens? After Kelo citizen activists defeated 44 projects to abuse eminent domain and the Supreme Court's main reason for upholding this was that there's a very troubling history when judges have tried to second guess economic legislation, striking down minimum wage laws or maximum hour laws or the entire regulatory state. And because of the danger of economic judicial activism, the Supreme Court said it's better to have citizen activists protect rights and legislatures rather than judges.

QUINNAnd that's actually happening. I mean, where many states have passed laws that really start to address public use and put limits on it, it would probably preclude a Kelo-like situation.

REHMAnd here's an example of exactly that. John in Cleveland, Ohio writes, "A few years ago, we had a class action suit against local government. The suburb of Lakewood wanted to seize land for a private contractor to build a shopping mall. The mayor, at that time, wanted to declare eminent domain under the guise that the area was blighted using some building code rule that 95 percent of the suburb was in violation of. This building code was that garages had to be attached when most are detached. The public fought back and the city and the mayor lost." Lew.

WIENERI remember that case and again, it came down to what was the definition of blight and the idea that a carport was evidence of blight was just preposterous. But I think two things weren't mentioned. One is with respect to the Kelo case there was no requirement that there be a finding of blight in order to trigger the taking. And that's critical because that gets down to the question of what are the conditions precedent that must be satisfied before a -- the government can exercise its right of eminent domain.

WIENERThe other point is, Kelo really won. Even though Kelo lost, I think that we look at it, 42 states enacted anti-Kelo legislation in the aftermath of the Kelo decision. I don't think that Mrs. Kelo could have done any better for the cause of eminent domain had she won that case.

ROSENAnd that really raises the question, are we afraid that these takings involve the government giving giveaways to private corporations, trying to favor one corporation over another as a result of lobbying or corruption? Or do we have faith in the political process, if there's a project that goes bad will the majority of citizens rise up in righteous indignation and pass laws that restrict excesses in the future?

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Here's an email from Dee Marie who says, "Born in 1952 I remember the anguish and despair and fight of my family. The Indiana Toll Road was trying to take a swath through our farm, my grandparents' farm and my great aunt's farm. They were organizing other affected farmers to fight for our land. Then, as now, only those directly affected cared. We lost. The road went through and was only to be a toll road until paid for, then a freeway. That never happened."

ROSENThat's the nimbiism (sp?) problem. You know, if not in my backyard...

REHM...so I won't worry about it. And if it is in my backyard I'll go fight for it.

ROSENAbsolutely.

WIENERAnd that's really -- if you want to talk about what the true impact of Kelo, there is an argument, and I think a sound argument that Kelo really didn't change the law. But what it did was it focused attention on the issue. And it's the -- it's not just what's happening in my backyard but my backyard today, my front yard tomorrow.

QUINNBut let's also keep in mind that one impact of the Fifth Amendment is that those kinds of takings are disclosed. They are public. People know about them and they do have the opportunity to react. And that the owners do go through a legal process and they are compensated. It doesn't make everything right but at least we have those protections.

REHMWell, the question becomes, as you said, Michael, with more and more people, more and more needs, more and more crowdedness, are we going to see more of these cases?

QUINNWell, I think it's inevitable. I mean, you're -- we're seeing issues now that the founders never thought about. You know, preserving watersheds so that cities have quality drinking water, which of course is an undeniable public benefit. So the range of impact we're dealing with was just not even conceived of at the time.

REHMYou know, if you think about even the Keystone project and Nebraska's objections because of its water table. And here you've got New York protecting its. So you're going to have more and more people, I think, concerned about water and takings. Thank you all so much. What an interesting discussion of the Fifth Amendment, which we so often think of one dimensionally. But it has so many broad ramifications.

REHMJeffery Rosen of George Washington University, Michael Quinn of James Madison's Montpelier and Lewis Wiener of Sutherland, Asbill and Brennan, former trial lawyer of the U.S. Department of Justice. Thanks for listening all. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.