Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

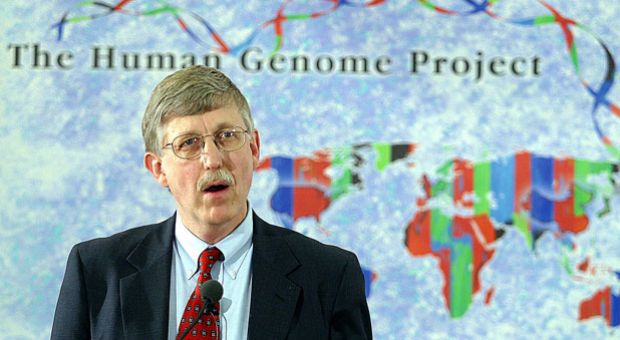

NIH Director Francis Collins, then-director of the U.S. National Human Genome Research Institute, announces that a six-country consortium has successfully drawn up a complete map of the human genome, completing one of the most ambitious scientific projects ever and offering a major opportunity for medical advances, April 14, 2003, at a press conference at the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Md.

The National Institutes of Health is joining forces with private industry to find better treatments for some of our most intractable diseases. This unusual team effort will target Alzheimer’s, Type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Another research partnership was also announced last week. Two U.S. foundations and one Canadian said they will offer joint research grants to examine the similarities between Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Diane talks with the director of the NIH, Dr. Francis Collins, about the promise of collaboration to fight disease.

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, sings an original song about the ubiquity of disease and need for health research. “Disease don’t care if you’re black or white, disease don’t care if you’re left or right, disease don’t care if you’re rich or poor, disease will find a way to come a-knocking at your door. So come on people won’t you join me please? Let’s get it all together and knock out disease,” he sings. Collins also points out the DNA double helix in mother of pearl carved into his guitar’s fretboard.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. A wave of research collaboration is underway to find better treatments for some of humanities most devastating diseases. The NIH is teaming up with drug companies to tackle Alzheimer's, Type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Separately, three foundations just announced they'll offer joint research grants to study Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

MS. DIANE REHMJoining me in the studio to talk about these partnerships and the promise they offer, Dr. Francis Collins. He's director of the National Institutes of Health, former leader of the Human Genome Project. Do join us with your questions, your comments. The number to call is 800-433-8850. Send an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. Dr. Collins, it's always good to see you.

DR. FRANCIS COLLINSDiane, it's always a privilege to be on your show.

REHMAnd Dr. Collins has with him his beautiful guitar. And tell us about the song you're written.

COLLINSWell, we're going to talk this morning about some new ideas about how to speed up the process of developing effective treatments for diseases like Alzheimer's and diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. And the urgency is considerable for any of us who are affected or our family members are. We're in a hurry.

REHMYou bet.

COLLINSWe want to see this get done. And the only way it's going to get done is if we all kind of work on it together, which is a new thing that we announced last week that we're going to talk about. But at some risk of destroying the dignity of your program and perhaps ruining any fundraising efforts that are currently underway, I was encouraged to bring this guitar, which, by the way, does have a double helix in mother of pearl on the fret board.

REHMIt's gorgeous.

COLLINSIt's a very special instrument indeed.

REHMGorgeous.

COLLINSAnd I wrote this song about disease. And the disease is sort of out there waiting, and disease doesn't care too much about a lot of the other things that we might think would protect us. So we better get together and work on this. So, with apologies to the listeners, here we go -- who probably wonder what radio station have I tuned into.

COLLINS(Singing) Well, disease don't care if you're black or white. Disease don't care if you're left or right. Disease don't care if you're rich or poor. Disease will find a way to come knocking at your door. So, come on, people, won't you join me, please. Let's get it all together now and knock out disease. Let's knock it out, people. Disease don't care if you're old or young. Disease don't care about your mother tongue. Disease don't care about your life's pursuit. You can wear a hoodie or a three-piece suit.

COLLINS(Singing) So come on, people, won't you join me, please. Let's get it all together now and knock out disease. Knock it out. Disease don't care if you're first in the class. Disease don't care if you came in last. Disease don't care if you're an R or a D. Disease don't even care if your party is Tea. So come on, people, won't you join me, please. Let's get it all together now and knock out disease.

COLLINS(Singing) So it's pretty clear that we're all at risk for cancer and strokes and ruptured discs. If you don't want to be left in the lurch, your very best hope is health research. Disease don't care if you're a big movie star. Disease don't care if you live in your car. Disease don't care if you just go with the flow. Disease don't even care if you're a CEO. So come on, people, won't you join me, please. Let's get it all together now and knock out disease. So come on, people, won't you join me, please. Let's get it all together now and knock out disease.

REHMYay. That was fabulous. Congrats.

COLLINSWell, thank you for the opportunity to be heard by many more people than usually listen to my particular...

REHMYou're going to have to record that. Really, it's terrific.

COLLINSWell, I've always said in this business of medical research, especially given the current funding climate, you've got to laugh, or you'll cry. So...

REHMAbsolutely.

COLLINS...that's what we're trying to do here, Diane.

REHMWell, thank you so much for that wonderful performance. Dr. Collins, last night on "60 Minutes," there was a segment on drugs and the different ways drugs interact with men and with women. And what we're finding out, according to that report, is that we're going to have to go back to ground zero to really understand the impact of how these drugs are really gender-based.

COLLINSWell, this is a very important issue. It's part of a larger theme of personalized medicine that the idea that we can come up with therapies that are one-size fits all and have them actually work for everyone isn't very well grounded in biology. I mean, for a long time, maybe that was the best we could do, but we could do better now. Certainly at NIH, we have a huge investment in trying to understand gender effects in terms of the impact of disease and the way in which interventions work or don't work.

COLLINSThe Women's Health Initiative, which has now been underway for 20 years, has given us a wealth of information, much of it unexpected, about differences between men and women, both in terms of how disease occurs and what you could do about it. But going even beyond gender, not all men are the same, and not all women are the same.

REHMExactly.

COLLINSAnd children are not small adults. So if we really want to have medicine work for everybody in the optimum way, we have to understand those individual differences and be prepared to adjust our therapies and our prevention strategies accordingly.

REHMGood. Tell us about the Accelerating Medicines Partnership, AMP.

COLLINSAMP, yes. We are amped up about this, and let me amplify about what happened last week. I'm very excited about this, Diane. What's the reason to mount this effort between NIH and 10 pharmaceutical companies? What are we all about here? Well, it still takes about 14 years to go from an idea about a new treatment for a disease and go all the way through the preclinical and the clinical trials and ultimately get approval.

REHMFourteen years.

COLLINSFourteen years. And the current failure rate is over 99 percent. And, you know, an engineer looking at that pipeline would say, come on, we got to do better than that. And the most frustrating failures are those where you get all the way to the end of that 14-year period and you have a drug that you thought was so promising and you do this big clinical trial and it just doesn't work. It's safe, but it doesn't help people with the disease.

COLLINSSo at that point, your conclusion has to be you picked a drug that hit the wrong target. When we talk about a target, basically most drugs are aimed to go somewhere in the body and influence another protein or a pathway, either by activating it or inactivating it. And it's really important to pick the right target. Otherwise you get to the end of this pipeline, and it doesn't help.

COLLINSThe problem has been our targets in the past have been chosen on the basis of rather squishy data sometimes, on an animal model that maybe wasn't really very much like the human disease or even a cell-based model. But we have a wealth of new opportunities coming out of new technology, particularly in genomics, the study of human DNA and the experiments of nature that are walking around amongst us that have variations in DNA that give us clues about whether particular pathways are important in human disease.

COLLINSSo more than 1,000 new drug targets have emerged in the last five years from that kind of study, but it's very hard to sift through them and pick out which ones are going to be the real home runs that we're all looking for. Drug companies look at this and go, ugh, too many opportunities. We can make sense of this. Academics look at it and say, yeah, we'd like to help, too, but we're not quite sure what the companies are looking for. No single entity can tackle this really exciting opportunity.

COLLINSSo let's all get together. So beginning almost three years ago, in conversations I've had with heads of R&D in big pharma, we have hatched what has ultimately come forward last week as this accelerating medicines partnership where 10 companies will pool their science and their resources with NIH investigators and for Alzheimer's disease, Type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, we will make the most of this special opportunity to find the right targets that the companies can then really go after with all of their competitive juices and make something happen.

COLLINSBut this part is going to be open access. This early part is let's all do this together. Let's not hide anything behind a curtain. Let's see what we can learn that's going to transform our understanding.

REHMSo that means each company and each research lab is going to share the information. Tell me why you settled on four problems rather than one.

COLLINSWell, you know, when we first started having this conversation with the companies, I wanted to do everything. Having had the experience of leading the Human Genome Project, I think comprehensiveness is a great thing if you can achieve it. And the companies were like, well, now wait a minute. Let's have a little focus here.

REHMYeah, right.

COLLINSSo we went through a fairly long careful process asking the companies what are the diseases that you are most interested in starting with. This is a start. This is not all of AMP, but it's where we're beginning. And out of that came Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, in this case rheumatoid arthritis and Lupus and schizophrenia was on the list at the...

REHMAnd you wanted schizophrenia on the list.

COLLINSI really wanted to see schizophrenia included because this is a disease for which we desperately need new treatments, and the number of people affected is enormous. Ultimately, we couldn't get enough critical mass of companies for that one.

REHMDr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health. Short break here. Your calls, I look forward to speaking with you.

REHMAnd welcome back. Dr. Francis Collins, the director of NIH is with me talking about the new Accelerating Medicines Partnership. Ten big drug companies that have spent billions of dollars sort of racing each other to find breakthroughs on diseases like Alzheimer's, Type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus are now going to partner. Who's going to pay for this partnership, Dr. Collins?

COLLINSWell, this is full 50/50 skin-in-the-game kind of collaboration, $230 million committed to this over five years, half of that coming from NIH, half of that coming from the 10 companies that are participating. The scientists from both sectors will sit around the same table and work together to make this happen in a fully open access atmosphere.

COLLINSWe already have detailed research plans for these disease areas that have been worked out over the past year with very clear milestones that have to be met. This is not one of those where everybody goes off and plays in the lab. We are really serious here about making real progress.

REHMIt's very exciting. Then there's another partnership between American Canadian doctors' labs on specifically the links between Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease which, as you know, my husband has.

COLLINSYes, yes. Well, we've known for some time that these diseases are not entirely independent of each other. They have overlapping features...

REHMAbsolutely.

COLLINS...both in terms of their clinical presentation, but even in terms of the pathways in the brain that seem to be affected when you look very closely at the molecular basis of the disease. So it makes sense not just to have those research efforts traveling along in a disconnected pathway, but to really try to see what can be learned by the overlaps.

COLLINSAnd that's what this effort aims to try to do. We have such an important opportunity and a responsibility when you consider the ways in which these diseases, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, have affected so many lives, both of individuals and of their families, robbing people of what should've been their golden years.

COLLINSAnd with our aging population, this problem is going to get even worse as we go forward if we don't come up with better answers. That's what all of us are committed to do. These are hard problems. The brain is the most complicated structure in the known universe. And to figure out how to intervene and how to do it early enough is going to take every bit of ingenuity that we can muster.

REHMYou know, it's been fascinating to me, George Vradenburg and his wife Trish Vradenburg, when George speaks to a huge audience as head of Us Against Alzheimer's, he says, OK, now half of you stand up and the rest of you sit down. And what he says is, this half standing will likely get Alzheimer's, and this half sitting will be caring for them. Is that how big that problem is?

COLLINSOh, it's an enormous problem. And, again, it is a disease of older aged people. So maybe back 100 years ago, we barely recognized the disease because very few people lived long enough to be affected. But now, when you consider that the risk of Alzheimer's really starts to go up in your mid-80s and 90s -- and that's where our longevity curves are going -- the consequences are severe in terms of suffering of individuals, in terms of costs. People estimate, by 2050, Alzheimer's disease may cost just our country a trillion dollars a year. We can't afford that.

REHMWow. Here's an email from Steven who says, "My mom and her mother both had early onset Alzheimer's. Are there any studies I should volunteer for?"

COLLINSYes, there are. So there are families in which Alzheimer's occurs in a strongly inherited fashion with onset sometimes as early as your 40s or 50s. And we're particularly interested in trying to study those families where you know the risk is very high because that might be the best opportunity to try out new therapies for people at very high risk who are willing to take on something that may or may not help them, and that might of course turn out to have side effects that you can't really predict until you do the trial.

COLLINSWe're running a very large study of that sort, NIH is, called Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Network, DIAN, run by the National Institute of Aging. And if you go to the website and just look under DIAN under NIH this person could find out more about it. What we'd like to do with Alzheimer's is to come up with strategies to begin treatment earlier. Many of our trials have failed in the past, but they were often tried on people who already had very seriously advanced disease.

REHMI see.

COLLINSWe know at that point that many of the neurons in the brain are already gone, and you can't expect to bring them back.

REHMAnd is that the same thing that happens with Parkinson's, that the neurons are gone?

COLLINSIn a different part of the brain, but, yes, to be sure. So in Parkinson's, it's a place called the substantia nigra where these cells that make dopamine normally are the ones that take the biggest damage from the disease. And, again, the earlier one could figure out how to slow or even stop the loss of those neurons, the better chance you'd have of a good outcome.

COLLINSSo we're shifting our clinical trial approach to try and identify people early in the course, or for some people maybe even before they have any symptoms, but they know they're at very high risk, like the person whose email you just read, in order to get the maximum chance to slow or stop the disease.

REHMYou know, it's fascinating to me that, at one point, before you could use any of these diagnostic methods, Alzheimer's was only specifically diagnosed on autopsy.

COLLINSYes.

REHMWhat was it that was seen in those autopsied brains?

COLLINSSo there are two pathological findings in Alzheimer's disease at autopsy. There are the plaques, and there are the tangles. And they're made up of proteins called amyloid and tau. And, as you say, until 10 or 20 years ago, that was the only really certain way to make the diagnosis. Now we have many other tools to help us that measure amyloid and tau without requiring a brain biopsy or an autopsy.

COLLINSImaging has come a long way. We now have the ability to look at anybody's brain and say, are they depositing amyloid? And for somebody who's on the path towards Alzheimer's disease, you will see that. It's a little bit challenging however because there are people who seem to have a fair amount of amyloid and who don't have Alzheimer's and don't develop it. So there's something else going on there. Just very recently, in the last year or so, it's become possible with imaging also to see tau, this other protein that's part of the disease.

COLLINSAnd one of the things we're doing with AMP, this Accelerating Medicines Partnership, is to get all of the clinical trials that are currently underway or about to start for Alzheimer's disease and be sure that all of these biomarkers are made available. So we will be looking at tau. We will be looking at amyloid. We'll be looking at a lot of blood tests. We'll be looking at spinal fluid. You want to find out every possible correlate to whether that drug is working or not at the earliest moment.

REHMAnother email from David who says, "What's going on with finding a cure for ALS? I often feel it's the forgotten disease. As an ALS patient, I'd like to know."

COLLINSALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, often called Lou Gehrig's disease, is indeed one of the most difficult, frustrating, heart-wrenching conditions that we see where individuals who've been entirely healthy develop progressive weakness because the motor neurons in the spinal cord are in fact the ones that are under attack. And we don't understand, in most instances, what is causing that attack.

REHMBut the brain itself, the thinking part of the brain is not affected.

COLLINSIs intact. So these individuals become almost locked in because ultimately even their breathing doesn't work the way it's supposed to because of a degeneration of these neurons in the spinal cord. There is a huge effort underway to find treatments for ALS sponsored by our neurology institute. And it's been pretty frustrating, I must say. There have been numerous examples where animal models of ALS -- there's a mouse model -- seem to have been benefitted by various interventions.

COLLINSWhen those have been tried in human patients, they have generally been unsuccessful -- not that we are in any way discouraged or giving up on this because there are new ideas coming along every day. But I would want the person writing the note to know this is a very high priority for all of us at NIH.

REHMDr. Collins, you know quite well about the so-called war on cancer. And we know that cancer may have surgical procedures. It may have radiation, chemotherapy. But we have not found out why, except in terms of lung cancer in relationship to cigarettes, for example. Will these studies called AMP go for causes as well as treatments?

COLLINSThey will in the sense that we are really trying to make the most of everything we've learned in terms of hereditary risks, in terms of environmental exposures, and bring that to bear initially on the diseases we've mentioned, but ultimately much more broadly. Cancer, in many ways, is ahead of the rest of the field because cancer is something that comes about because of mistakes in DNA. And we are able now to catalog those at a prodigious rate.

COLLINSSo we have so many drug targets for cancer now that we know would be effective if we could develop drugs that would hit those targets. And people are moving forward on that at a prodigious pace. But why does cancer happen? Well, you've said it quite accurately. We know some of the environmental reasons, cigarette smoke being the largest but not the only one, radiation being another.

COLLINSWe know there are hereditary influences, the famous BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, but others as well that are not quite as strong in their effect. But sometimes we can't come up with an answer. And sometimes it may just be that when your cell has to copy its 3 billion letter instruction book, it makes a mistake in the wrong place. And that causes that cell to grow when it really shouldn't have. Some parts of cancer may in fact not have a cause other than the error prone nature of copying this amazing genome that we have inside each cell. And it has to be copied each time.

REHMDr. Francis Collins, and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Dr. Collins, you know that there are critics of the partnership who don't think this is the best approach or who happen to disagree with the diseases you've chosen. What do you say to the critics who say, why is Alzheimer's at the top of the list? Why is lupus in there? Why is arthritis in there?

COLLINSWell, I would first say that these are pilots to get us started. And I'm also hopeful that we will add many other diseases to the list once it's clear that this model works. But I think there is skepticism about whether scientists from the private sector and the public sector can work together. Can we actually achieve some of these very ambitious milestones, or will this whole thing fizzle?

COLLINSI don't think it's going to fizzle. I will put every bit of my energy into making sure it doesn't. And I've been -- I'm very involved in this project. But people do want to see some evidence of success before expanding to every possible disease.

REHMHow much competitiveness will there be among the drug companies?

COLLINSWell, in this phase of trying to identify the next generation of drug targets, everybody agrees that this is precompetitive, and that is that all the information has to be openly shared both within this consortium and for anybody else who's watching. So we hope to crowd source good ideas by people who are watching this whole enterprise unfold. The competitiveness, Diane, kicks in once you've identified, oh wow, that particular molecule is a really promising target for the next generation of Alzheimer's therapy.

COLLINSThen every company will run off and do what they do really well to design a (unintelligible) antibody or some small molecule drug that they think they can beat their competitors with. And we want them to do that. That's good competition. That means that things move quickly and there's lots of ways that you can get to yes.

REHMBut at some point they're going to move off on their own. How long with the process be open? How long will they share their own research?

COLLINSSo this phase of taking all of the information that you can derive from cell models, from animals models, from human genetics, from imaging and synthesizing it into what we would call a knowledge portal, should enable anybody who wants to identify that next set of targets to do so in a completely open fashion. That will continue to be open. But as soon as a company decides, I've not just identified a target. I'm going to try to build a therapy that hits that target, then they move into the competitive phase.

REHMBut do they decide that on their own? I mean, how long are you promising that it will be open?

COLLINSIt will continue indefinitely for this phase of finding targets. But if a company along the way...

REHMOh, I see.

COLLINS...sees one emerge that they really like, they will start chasing after it, even as we see whether the list is ideal or whether there are other targets that haven't emerged yet.

REHMAnd is that the same with the American Canadian partnership on Alzheimer's and Parkinson's looking for similarities and differences?

COLLINSAgain, I think the intention there is to have that be information that everybody can share. You know, something Mikael Dolsten said -- who's my colleague at Pfizer who's been a real leader in the AMP effort -- is, the goal here is to get yourself on the right road. Companies want to go really fast once they have the right target. But if you're going to drive fast, it's good to know you're on the right road and not the road that's going to lead you over a cliff.

REHMAnd if you want to go fast, you may be more prone to make mistakes.

COLLINSWell, all the more reason why you want to start in a very solid foundation knowing that what you're going after is in fact tightly connected to the human disease and therefore likely to result in benefit to people who suffer from it.

REHMI'm interested that Johnson & Johnson hired Yale University to oversee the sharing of clinical trial data. What can you tell us about that?

COLLINSI think that's fascinating. So the person at Yale University, Mr. Harlan Krumholz, who's a cardiologist, who is a wonderful leader in this whole idea about getting information out there where everybody can see it -- and he has a lot of credibility so people will believe that if Harlan is involved that what Johnson & Johnson proposes to do is the real deal and not just some window dressing. I think it's great.

REHMDr. Francis Collins, he is director of the National Institutes of Health. And, just to give you a heads up, if you happened to tune in a little late today and did not hear Dr. Collins perform his wonderful song, we'll have it for you again at the end of the program. Right now, call us, 800-433-8850, and stay with us.

REHMAnd welcome back to a conversation with Dr. Francis Collins. As you know, he is the director of the National Institutes of Health and is very excited about a new project, which will combine the works of 10 drug companies and the U.S. government at NIH, focusing on four primary diseases: Alzheimer's, lupus, arthritis and...

COLLINSAnd diabetes.

REHM...and diabetes. All right. Let's open the phones here, 800-433-8850, first to Laura in Houston, Texas. You're on the air.

LAURAHi. Thanks so much for having this fascinating conversation. My question lies in large part to the relationship to these diseases and the research being done linking our diet to the causation. I am gluten intolerant and found out about a diet where I reduced all of my carb intake to monosaccharides. And, after about two weeks, my arthritic pain went away. My neuropathy shakes went away. My -- I didn't know I had an anxiety disorder. That went away.

LAURAAnd then, through a series of events, I ended up running a kitchen cooking large-scale meals for summer camp and reintroduced regular sugars and some of the other things, and it kind of spiraled me into a depression. And now that I've cut it back out, those things have gone away again. And I'm wondering...

REHMOK, Laura. Let's get to the question of diet.

COLLINSWell, there's a lot of really interesting research going on right now, trying to figure out how dietary differences can affect a whole host of conditions. And I've got to say, one of the connections there that's really beginning to emerge is the way in which our diet influences the microbes that live in our GI tract, which may be something that you don't like to think about, but they are really important.

COLLINSAnd they are there mostly to actually assist our good health, but they can get out of whack and cause a wide variety of problems. And, certainly, when you alter your diet, you alter what we call your microbiome, all of these organisms, which, by the way, when you start counting them up, there are more microbes that live on us and in us than the total number of cells in our body.

COLLINSThey've got us outnumbered. So we probably ought to pay attention to them. And very recently, people are beginning to discover connections between that and diabetes and obesity. Very recently, an exciting story about how this is connected to autism and that you might, therefore be able to modify the microbes and have benefit for a condition as troubling as autism. Wouldn't that be amazing?

COLLINSAll right. And on that very subject, let's go to Miramar, Fla. Lawrence, you're on the air.

LAWRENCEGood morning, Diane.

REHMHi there.

LAWRENCEYeah, thank you for taking my call. First time caller and long-time listener.

REHMGood. Thank you.

LAWRENCEYou're welcome. I just want to ask your guest if they have any plans for autism patients.

COLLINSAbsolutely. Autism is a very high priority for research for a number of our institutes that study childhood diseases and neurological problems. And, as you know, autism is becoming more and more common for reasons that we don't entirely understand. In about 15 or 20 percent of cases with autism, we can actually identify a DNA change, a genetic misspelling that contributes to the disease. But that doesn't account for the rest. Again, I just mentioned this recent observation that there may be a connection to what's going on in terms of the microbes that live in the GI tract.

COLLINSAnd there's often been a suggestion that autism and intestinal troubles go together. Don't know quite where that's going, but it's one of the more recent exciting clues. There's a very highly organized effort to try to tap into every bit of information we can from genetics, from the environment, and get this figured out.

REHMAll right, to Adriana in Atlanta, Ga. Hi there.

ADRIANAGood morning, Diane. Thank you for taking my call.

REHMSurely.

ADRIANAAlong some similar lines and also tying in the Alzheimer's component, I've got a two-part question. My mother showed symptoms of Alzheimer's at 70, and she is now 80. And the disease continues to progress. Her mother had it, mother's mother had it, so, of course, I'm very aware of it and concerned. And so I'm interested in probability of getting the disease. And then, second to that, I happen to have a daughter with Down syndrome. And, as we know, the brain presents very similarly in a person with Down syndrome as it does for a person with Alzheimer's.

COLLINSMm hmm.

ADRIANASo as we move forward and look at these new drugs to help persons with Alzheimer's, can it then be applied to a person with Down syndrome to help with the tangles and the plaques that accumulate?

COLLINSWhat a great question. The gene for amyloid that I mentioned builds up in the brain is on chromosome 21.

ADRIANAYeah.

COLLINSChildren with Down syndrome and adults with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21. So they make 50 percent amyloid than does somebody who doesn't have that condition. We think that's probably the connection. But you raise a wonderfully important question. I mentioned earlier how we're trying to shift our clinical trials in the direction of starting as early as possible with people at very high risk. Well, Down syndrome adults are certainly in that category.

COLLINSAnd there are discussions about whether it would be a good idea basically to make available at the earliest stage, clinical trials of preventive strategies for Alzheimer's to individuals with Down syndrome. We're looking at that quite actively. Obviously, lots of ethical questions there in terms of who gives the consent. And suppose there turns out to be some unfortunate side effect -- you never know when you're starting a clinical trial. Got to work through all of those things. But it's a very interesting question you've raised.

REHMAdriana, I'm so glad you called. Thank you. Let's go to Matthew in Pepper Pike, Ohio. You're on the air.

MATTHEWHello, Diane. How are you?

REHMGood, thanks.

MATTHEWHi. I think the first caller, speaking about diet, had some of the most valid points I've heard. I would argue that humans today don't get the same levels of proteins, antioxidants that our ancestors had. And that's why you're seeing these increases in plaque buildups in the brain, associated diseases, such as heart disease, in accordance with cancer.

MATTHEWThese things tie together. I would argue there isn't enough research on cannabinoids. I'm not saying it would solve everything, but I think there's some valid things to do. And just, overall, I think the pharmaceutical companies aren't really who we should be looking to for the answer. I think...

REHMAll right.

MATTHEW…there's just too much business influence.

REHMAll right. Thanks for that. What about that?

COLLINSWell, certainly diet, as the caller is suggesting, has changed a lot in the western world over what humanity experienced for most of its history. And there is clear connections there with things like heart disease and hypertension, Alzheimer's, less clear what the dietary connection may be, because we really don't have good information going back many centuries, because most people didn't live long enough to develop this condition so we're not quite sure.

COLLINSWith regard to the drug companies, I know that people are concerned about what their motives are. Again, they make pills. NIH doesn't. If we want to see a therapy that's brought all the way through to a conclusion and the FDA approves it and you can go to the drug store and get a prescription filled, the drug companies are the ones who do that. We believe, by working together, we can speed up the process of getting the right answers.

REHMWhy do you think the drug companies are willing to collaborate at this point?

COLLINSGood question. You know, five years ago, I don't think this would have been possible. I think it's a combination of scientific opportunity that is so exciting but so overwhelming that no company can tackle it on their own, plus their own anxieties about the failures that are all too common, even now, in drug trials where you've spent hundreds of millions of dollars and you get to the end of that Phase III trial and it didn't work. They've had enough of that, and they're anxious to try something different.

REHMWhat about other countries? Have there been such collaborations?

COLLINSIn Europe, there are certainly efforts to bring together public and private sectors for the development of therapeutics, something called IMI, the Innovative Medicines Initiative. And, in fact, some of the drug companies that are part of our AMP program are not U.S. companies -- GSK is in Britain, for instance -- so we do have an international component. Almost all of research these days is international. We are, in fact, one global community.

REHMAnd do you think that that aspect of global is going to somehow figure into all this?

COLLINSI think it'll help. And, again, because we're doing this in an open-access fashion, even people who are not formally part of this AMP consortium, if they have an Internet connection, they're going to be able to watch what happens.

REHMDr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health. And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." All right, let's go to Al who's been waiting. He's in Fairfax, Va. Hi there, Al.

ALHi. Yes. I was wondering how the director, being a born-again devout Christian, affects his decisions in terms of -- I assume his colleagues would think that he's tampering with God's creation or that maybe the -- to prevent extreme genetic engineering, as the director. And I wonder if these colleagues are perhaps asking him to pursue the research of maybe homosexuality as a genetic disorder, to cure it? I'm just curious how that contradiction works in his daily life at work.

REHMAll right. Thanks for your call. Dr. Collins.

COLLINSWell, I don't think it's really a contradiction. I think, for myself as a Christian and for most people who either have a faith or don't, the idea of spending your time trying to find answers to human suffering is a noble activity and one that we should all pursue. When I look at the life of Christ and see how much of the time he had that we know about was spent reaching out to people who were hurting, suffering, struck with illness, it seems like that was a pretty important model for us to pay attention to.

COLLINSSo I feel enormously blessed to have the opportunity to spend my time chasing after answers for Alzheimer's or diabetes or lupus or rheumatoid arthritis or cancer or whatever disease is afflicting somebody. Every little bit of progress we make there, it seems to me, is very much part of God's plan.

REHMWhen someone refers to you as a born-again Christian, what does that mean to you?

COLLINSYeah, that throws people, doesn't it?

REHMYeah.

COLLINSI was an atheist until I was 27 years old. And I encountered the rational arguments for faith, much to my surprise, as very compelling and resisted those for a good couple of years while earnestly trying to understand why believers believe and ultimately concluded they were right. So I started my life over again.

COLLINSI guess you could call that being born again, although I know that term is sufficiently confusing to some people, that they think it sounds maybe a little odd. It was not odd. It was the most remarkable transition in my world view that I could possibly imagine and one that's really the rock I stand on now.

REHMAnd how do you believe it affects your thinking about the work you do?

COLLINSYou know, when I sit in a room with lots of people trying to decide, what's the right thing to do about medical research, I think we all have that same foundation of morality of, what's a good thing and what are the things we should avoid? You might ask where that comes from because it isn't always leading you to a conclusion that evolution would say is a good way to propagate your own DNA.

COLLINSThat's actually one of the arguments, I think, that brought me around to considering whether there's more than just naturalism to explain the nature of humanity. But I don't introduce my faith into science conversations. I don't think that would be appropriate as NIH director. I would certainly not want anybody to think I'm trying to proselytize.

REHMYou know, when we think about radiation, chemotherapy treatments for cancer, the saying goes, you well know it's either going to help you or kill you so that the idea of using experimental drugs on even patients with Alzheimer's or patients with cancer, does that give you pause?

COLLINSIt gives me pause. But it's the only way that ultimately we're going to save lives. I have a dear friend who lives in Michigan who's just been getting an experimental treatment at NIH for her brain tumor. She is on a grand adventure that may help her or may not. But, if it does, maybe it will help all of us in the future. It takes a certain amount of courage to sign up...

REHMYou bet.

COLLINS...to sign up for one of these trials, which may or may not help you. But it is, in fact, one of the most important things we can do right now to move beyond our imperfect solutions to something better.

REHMAll right. And one last caller from Indianapolis. Ray, you're on the air.

RAYYes. Thank you. My question is about drug targeting. Targets are often identified, but we don't seem to do a good job getting the drug to the target. It's almost like, if there were a fire at your break room there at WAMU, we would flood the city of Washington D.C. to put the fire out. Do you have any specific focus in this new effort to target drugs or do specific drug delivery once targets are identified?

COLLINSWell, there's a lot of research going on in that area. And you're right to ask the question. Much of that is, in fact, competitive work going on in the drug companies. Once they've identified what target they want to go after, they want to be sure that they're hitting it in the right organ, at the right level, with the least amount of side effects.

COLLINSAnd there are all kinds of clever schemes available now to do that kind of targeting. That's not part of our Accelerating Medicines Partnership. It's something that happens downstream and we hope will happen in great proliferation once people are excited about the targets they can chase after.

REHMDr. Collins, I promised listeners that you would perform once more for those who did not get to hear you in the beginning. Before you do, let me just say thank you once again to Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health. Thank you so much for being here.

COLLINSIt's been a lot of fun having this conversation with you and your listeners.

REHMThank you.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.