Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Guest Host: Tom Gjelten

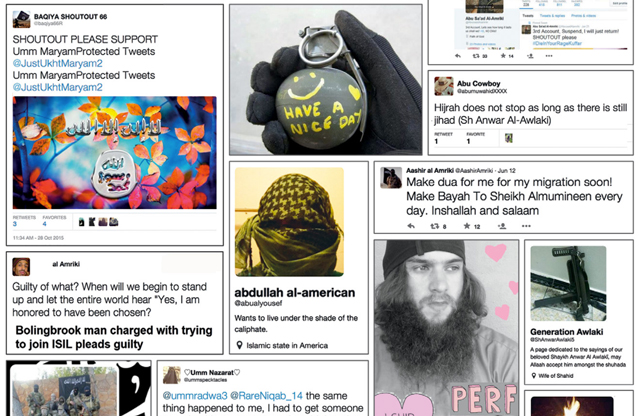

Social media posts collected by the authors of "ISIS in America: From Retweets to Raqqa," a study of "U.S. persons arrested, indicted, or convicted in the United States for ISIS-related activities," and of "ISIS-related mobilization in America."

Investigators are now saying the two people behind the San Bernardino shooting had been radicalized long before their killing spree. For many like them, social media can play a big role in that process. Sites like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are now wrestling with how to identify material related to terrorism, and then what to do with what they find, toeing the line between upholding free speech on the web and removing dangerous or influential content. Both president Obama and presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton have recently called for increased cooperation between the government and these companies, which have shown reluctance in the past to wade deeper into this complicated issue. A conversation about how to deal with terrorist content on social media.

MR. TOM GJELTENThanks for joining us. I'm Tom Gjelten of NPR sitting in for Diane Rehm. Just before she and her husband shot and killed 14 people in San Bernardino, Tashfeen Malik went on Facebook and declared her allegiance to ISIS. It's just the latest in the story of the relationship and terrorism and social media. ISIS makes use of tools like Twitter for radicalization, communication and planning that puts pressure on social media companies to step up efforts to find terror-related content.

MR. TOM GJELTENBut how to do so and what to do with what they uncover? Lots of tough questions to consider and here to help us are Jennifer Golbeck of the University of Maryland and Paul Rosenzweig of Red Branch Consulting, both here in the studio with me. On the line from NPR headquarters in Washington is Lorenzo Vidino of George Washington University and from New York City is Lee Rowland of the ACLU.

MR. TOM GJELTENWe'd like you to be part of this conversation. I'm sure many of you have thoughts or questions about this trade-off between free speech and security. Our number is 1-800-433-8850. You can also email us, drshow@wamu.org. You can send us comments or questions on our Facebook page. You can reach us on Twitter. But before we get started, a special welcome to the listeners of WTGX, 93.1 FM, joining us for the first time today from the US Virgin Islands.

MR. TOM GJELTENJennifer, Paul, Lorenzo, Lee, thanks for joining us.

MS. JENNIFER GOLBECKGlad to be here.

MR. PAUL ROSENZWEIGThanks for having us.

MS. LEE ROWLANDThanks.

MR. LORENZO VIDINOThank you.

GJELTENLorenzo, let's start with you. I understand you've done a study looking at the use of Twitter by ISIS. Tell us, how is that group using social media these days?

VIDINOWhat we did for our studies, we looked at around 300 individuals that we assessed to be Americans who are ISIS sympathizers and active online, active on Twitter. And it's a small community, we called it an eco-chamber of these individuals who are interested in ISIS and ISIS ideology. And what they do is they use social media to speak and interact with likeminded individuals, to disseminate with propaganda and then, some cases they move to other platforms to then become operational, which means to mobilize, which means mostly traveling to -- or trying to travel to Syria and Iraq or to carry out attacks in the U.S.

VIDINOObviously, there are basically key disseminators, certain individuals who are not necessarily linked to ISIS, but are just individuals who are very active, very good at using social media and they are the key nodes in this community. So ISIS Central, let's say, from Syria and Iraq, puts out a lot of material, but then it's really up to individuals, whether they are in the UK, which is a big hub for these activities, or a few of them here in the U.S. may further disseminate it.

VIDINOAnd we also have cases of what I would call grooming. Dynamics that are very similar to what pedophiles do online where ISIS sympathizers identify vulnerable people and they reach out to them initially in a very soft way and try to attract them to their cause.

GJELTENWell, is there any kind of centralization of these efforts? Is there any -- do you see any command and control apart from these, you know, relatively decentralized nodes that you're referring to?

VIDINOThere is some, of course, centralization, meaning that ISIS Central in Syria and Iraq has its own media offices. There is some kind of strategy. But then, it's really, particularly in the West, left to some core individuals, who, as I said, are not necessarily formally affiliated to ISIS to be the main nodes, to be the one disseminating these efforts. ISIS ability is that of also having a very diverse propaganda that touches different chords, from some very nice narrative of come and build this Utopian society, with just society that appeals to certain to people, to some very violent images, which we all getting to learn, the beheadings and so on, that appeals also to another demographic.

VIDINODifferent sub communities form themselves when attracted to certain messages. But it's really decentralized. You already have individuals who are -- take it upon themselves. They are fan boys, using what is the term used in the internet communities, for ISIS and maybe have never really left their parents' basements. They are, in some cases, 19-year-olds who are just fascinated by the ideology and spend all their lives disseminating it.

GJELTENOn Twitter, mainly.

VIDINOIt's on Twitter. It's also on Facebook. It's increasingly shifting to less open platforms because there has been a partial crackdown so it's moving to -- which is problematic to some degree for law enforcement. It's moving to the dark web. It's moving to Tumblr. It's moving to Telegram, which is kind of the application of choice. And then, when it comes to direct communication, it's moving to encrypted platforms. A lot of these apps that, you know, a lot of teenagers use to talk, Snapchat, Wickr, which are very, very difficult to intercept for law enforcement.

GJELTENWell, Jen Golbeck, I'm sure tech companies know all about this, know what's happening. What's their response been?

GOLBECKIt's hard. They've looked at it in a couple different ways. One is that they know it's happening and when they find it happening, they shut those accounts down. In some cases, they actually report it to law enforcement. But the problem is the real volume of content that's out there because, yes, there is ISIS content. There is content from other terrorist organizations. And when we see that, we know what to do with it.

GOLBECKThe problem is there is so much other content that it's actually really hard, computationally, to find and identify that terrorist content. So if we look at YouTube, for example, ISIS has used that to post videos. Al-Qaeda affiliated organizations has used it. YouTube doesn't want it used that way so they have to find those videos and take them down. There's about 400 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute so how do you process 400 hours of video every minute.

GOLBECKIf you've every uploaded a video to YouTube, it takes a lot longer than that to upload it, right? There's a huge amount of computational power and it's really hard to find out which of those videos is terrorist. So Lorenzo just mentioned child pornography. They look for that, but there's a known database of pornographic videos and images that they can compare against. So there, you're just saying does this video have these images and they can kind of catch that.

GJELTENWhen you say "these images," of particular people or, you know...

GOLBECKThat's right. So the government, the FBI, other organizations collect illegal child pornography and have a database that places like YouTube or Facebook can compare against to check to see is this image pornographic. But they don't have that for terrorist videos and, of course, ISIS can make new videos. So how do you detect this is a terrorist video versus this isn't and the same goes for text and photos and posts on social media.

GOLBECKIt's really hard to find it in the vast amount of information that people are uploading and that's a real challenge.

GJELTENWell, Paul Rosenzweig, is there anything else that social media companies could do and aren't doing, maybe for political reasons or maybe for legal reasons or cultural reasons or?

ROSENZWEIGWell, all three, I would think. I mean, there's a great deal of hesitancy in the tech community to become the policemen of the network. Their zeitgeist, if you will, is about free exchange of information and that lies behind the hesitancy. On the other hand, I mean, we sort of have to realize that this is how the terrorist threat has morphed. Dennis Kilcullen, one of the great anti-terror, counterterrorism experts, calls it radicalization at a distance and the methodology is the social media network.

ROSENZWEIGIt is assuredly difficult to identify terrorist content, at least initially. It strikes me, though, that one of the things we haven't done enough of is trying harder to build that database, trying harder to get information in advance, trying to collect it and making it a systematized and as automated as we can. That won't solve the terrorist propaganda problem in much the same way we haven't solved the child pornography problem 'cause there are new child pornography videos as well.

ROSENZWEIGBut mostly, I think, because there's a difficult line between propaganda that we will accept and terrorist activity that we won't in the First Amendment, where that line doesn't exist in child pornography. There's -- yeah, nobody makes the argument that there's a difficulty in distinguishing what's really, really bad from what's really, really good.

GJELTENI want to bring you in, Lee Rowland, from the ACLU. We're talking here about censoring content. What kind of concerns do you have? I mean, obviously, I'm sure that your organization is concerned about terrorism, but what's your perspective on this?

ROWLANDWell, you know, I think any time we're talking about a major policy question, you have to ask a few questions. And the first is, you know, is it practical? Is it doable? And Jennifer's already spoken to why this is really complicated, right, in the online world, identifying the kind of speech that we're talking about and having some kind of bright line rule that makes us safer, right? I think that's illusory and we have to acknowledge that.

ROWLANDBut in addition to the practicality, we have to ask, is the policy decision consistent with our values and is it effective? And when we're talking about censoring speech online, I think the answer to both questions is no. And in addition to talking about just the potential negative civil liberties impact of, say, roping social media companies into being wings of the national surveillance state, which I think is problematic for a number of reasons, I think it's important for us to acknowledge at the beginning of this conversation that it's so easy to demonize social media or really any technology when it's been involved in any kind of violence or crime.

ROWLANDBut I really think it's critical to remember that we, as a nation, not just as people, but our government, has put immense amounts of resources into spreading social media to other parts of the world because we recognize that the digital world provides us, perhaps, the greatest opportunity for exporting liberal, democratic and constitutional values. So while we absolutely should have -- and, you know, this is a very important conversation for us to talk about how we do grapple with terrorism when it occurs online at the same time, let's remember that we are talking about a digital space whose impact is overwhelmingly positive for the values that we care about in America and one of our best tools in the toolkit in eliminating terrorism long...

GJELTENLee Rowland is senior staff attorney at the ACLU's speech privacy and technology project. We're talking about this difficult issue of how to deal with terror content on social media. Stay with us. We're gonna take a short break.

GJELTENWelcome back. I'm Tom Gjelten of NPR sitting in today for Diane Rehm. And we're talking about a very tough issue and that is the way that ISIS and other terrorist groups use social media and how can we deal with that? How can we oppose those efforts on social media without sacrificing free speech and access to the Internet.

GJELTENMy guests here in the studio are Jennifer Golbeck. She's associate professor in the College for Information Studies at the University of Maryland. Also Paul Rosenzweig who's a principal at Redbranch Consulting. He used to be deputy assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Homeland Security. From NPR headquarters in Washington, Lorenzo Vidino, director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University's Center for Cyber & Homeland Security. And on the phone from New York City, Lee Rowland. She's senior staff attorney at the ACLU's Speech, Privacy and Technology Project.

GJELTENRemember, our phone number is 1-800-433-8850, if you want to get in on this conversation. Already a couple of emails. You can email us at drshow@wamu.org. Emma writes, is law enforcement able to compel social media sites to take social media content down or monitor specific people? Important question. Also, Jude writes, I believe this idea that social media is causing violence is just an excuse to restrict people's freedom and tighten security on honest people. I worry the situation will be used to justify surveillance. Jennifer, I have an idea that Jude is speaking for a lot of people with that comment.

GOLBECKYeah, it's interesting. Because when I look at how this issue is being discussed, I don't see it as much as people saying social media is causing the problem, in the way you hear like violent video games caused mass shooting. I really see it more as social media is a communication platform just like any other that is, unfortunately, being used very effectively by terrorist organizations here. And then the question becomes, as Lee and Paul were just speaking to, how do you actually deal with that? Because there really is a concern.

GOLBECKAnd I was speaking before about the computational issues of automatically detecting this content. The way it's happening now is that people are flagging it, right? If I come across a post by someone that I think is supporting terrorist activity, I put up a little flag that sends a message to YouTube or Facebook that says...

GJELTENMm-hmm.

GOLBECK...this is the kind of stuff you don't want to have. And then they'll take that down. But the problem, as Lee sort of alluded to, is that that can very much be abused too. And we've seen that, for example, in the Ukraine, when there was the whole issue uprising there. Pro-Russian Ukrainians were kind of banded together and flagging anything from the kind of pro-Ukrainian side as supporting terrorism and it was getting taken down. We've also seen that in Vietnam where the government was using it to have things taken down. So there is this real issue of what counts and what doesn't and how do we handle it?

GJELTENPaul Rosenzweig, I'm sure you saw what Hillary Clinton said this weekend, where she came out very strong and said that technology companies need to step up and take on these terrorist groups. What was the reaction on the part of the companies to that? And what really can the government do to compel companies to do more than they're already doing?

ROSENZWEIGWell, the tech companies are very reluctant, I think, to be between a candidate and an election. That's one of the most dangerous places in Washington, D.C., or America to be. It does, you know, the tech companies have begun stepping up more. The rate at which Twitter and YouTube and Facebook are reacting to and taking down problematic accounts is increasingly greater. There was a great story in The New York Times today about how one ISIS account has been taken down 355 times and now it's up to number 356.

GJELTENRight. They just keep adding a digit at the end of their address.

ROSENZWEIGYeah. And in some sense, that's a bit like, you know, sweeping back the tide. But in another sense, that's actually a valuable action by Twitter because it increasingly makes it difficult. People always have to reset and find the new place to go. As for law enforcement compulsion, we, I think, as a society would really prefer not to go there. We'd prefer not to have the government forcing Twitter and Facebook to do takedowns. I think Mrs. Clinton was using kind of soft power of persuasion rather than that. And that's a pretty strong one. And there will be other reactions from the American public if Twitter didn't do this.

ROSENZWEIGIn the end -- and probably, I'm sure, Lee will disagree with this -- I think probably, in the end, the government could compel the takedown of designated terrorist organization accounts if it wanted to. There's a Supreme Court case, Humanitarian Law Project versus Holder, that in my judgment suggests that. But that's not something that, you know, even anybody really wants. That's not a road anybody wants to travel down.

GJELTENWell, Lee, are you like jumping to get into this conversation when you hear talk of compulsion?

ROWLANDWell, I'm happy to disagree, as Paul predicted. You know, I think one of the problems here that we have to recognize is that folks at Twitter and folks at Facebook and other social media companies are not experts on terrorism, right? So exactly as Jennifer was indicating, the problem in having these third-party takedowns, where you're inviting people who may have perverse incentives to ask that speech be taken down, we have this -- a different problem, but of equal magnitude, if we're also asking the companies to self-designate as, again, arms of the national security state. They are not ICE or DHS or FBI. These are folks who run a platform for speech.

ROWLANDAnd, you know, based on our American values, we have made a decision in our constitution that one of the best ways to deal with bad speech is to throw sunlight on it and to be able to identify it, to respond to it with our own better ideas. And so there really is, I think, a real question about whether we even want that speech taken down. Even assuming we could have a perfect world where we could identify, on one line, all speech that supported ISIS. Simply agreeing with the values of another group -- no matter how offensive, even if they are listed as a terrorist registry -- is not akin to providing material support to that group. It is still speech.

GJELTENWell, will the -- what about if it's...

ROWLANDAnd, you know, it's a question about all speech, no matter how offensive. It's protected.

GJELTENLet me jump in. What if it's -- goes beyond propaganda? What if it is actually communication, operational instructions passing back and forth, something like that, something that really goes beyond just speech and messaging?

ROWLANDOh, well, absolutely. We have lots of precedent that suggest that when you are operationalizing a crime, that even if it may be made of words at time, that that is not entirely protected by the First Amendment. It may be conspiracy. It may be material support for terrorism. But I don't think we can kid ourselves that executives at Twitter or Facebook are going to be able to separate that wheat from the chaff of everyday protected speech.

GJELTENOkay.

ROWLANDAnd we know that companies round up. They have a history of doing so, in fact. Apple at one point had a -- had repeatedly rejected a program that allowed people to report American drone strikes and victims of American drone strikes, because it was considered objectionable content under a kind of U.S. national security viewpoint.

GJELTENYeah.

ROWLANDAnd so there really are consequences.

GJELTENMm-hmm.

ROWLANDSpeech gets rounded up and we lose valuable speech if we ask companies to self-designate as terrorism experts and draw that line for us. It's not going to be precise. And we are going to have the speech of innocent Americans swept up, scrutinized and perhaps censored.

GJELTENOkay. Lorenzo Vidino, so the U.S. government is constrained by the constitution. Tech companies are constrained by their own -- their own business interests, commercial interests. One group that is not constrained by either of those is anonymous. And I understand that Anonymous has been taking on some of this responsibility for going after ISIS and its related groups. Are you up to speed on what the Anonymous hacking group has been doing in this regard?

VIDINOYeah, you have Anonymous, you have another -- a lot of other groups actually also here in the states. The concerned citizens, who have been flagging, taking down and taking a lot of those actions. I think it's mixed results because even, I guess, a powerful group like Anonymous has its limitations, what it can do. Accounts, once they get taken down, one way or the other, reappear and there's a system in place for ISIS sympathizers to recreate accounts and have everybody follow them right away. So it's not exactly that effective.

VIDINOI think there's another perspective we're probably missing here is the one from law enforcement. And to some degree, law enforcement would actually disagree that taking down these accounts is a good thing because they glean a lot of intelligence from having those accounts up. Sure, they understand that form a radicalization point of view it creates a problem. At the same time, how else would you detect individuals who are ISIS sympathizers if they were not active on Facebook, on Twitter and so on.

VIDINOThese are people who have no operational connections to ISIS. So it's not like in the al-Qaida days where there's communication back and forth with Pakistan or Yemen. These are people who are here and the only way that can appear on the radar screen for the most part is the fact that they are online. And if you see the cases, for example, the 71 individuals who have been arrested over the last year and a half in the U.S. for ISIS-related activities. The vast majority of them, the investigations started when the FBI detected certain activities online -- detected the individuals online.

VIDINOSo there's a value there. I think it's a very complex issue there. If can add somewhat of a philosophical point during all this. And I think there's, of course, a lot of talk about social media and so on, the importance of it, which is undeniable and our studies showed it, that it's undeniably important for the ISIS-related immobilization. But we're focusing on the tools used and not on the message used. There's lots of groups that use social media, all kind of extremist ideologies. There's a reason why ISIS is more attractive and it's a message that it sends out.

VIDINOSo the political debate is focusing a lot on the kind of -- how the message is spread by ISIS. But if -- it's like in marketing. You can have a great marketing campaign, but if your product is not good, doesn't have a good -- an appeal, people are not going to buy it. So I think there should be a bit of a refocusing on what we're looking at.

GJELTENJennifer, the focus here in this conversation so far has been on sort of the negative techniques, you know, taking down websites, going after companies. Is there any kind of positive counterpart here that we might talk about? Lorenzo was just talking about, you know, the use of social media for, let's say, for storytelling purposes. Is there any way to sort of encourage a kind of a, perhaps Muslim communities to use social media in a kind of a proactive way to kind of preempt some of these messages?

GOLBECKYou know, I think Lee kind of raised this issue of shedding light on these sorts of things and countering this perception is a really powerful thing we can do on social media. My favorite example of that, that I've seen so far, is the Humans of New York Facebook page, which is extremely popular, millions of followers. And it's traditionally a photographer and he's in New York and he takes pictures of people hanging out there and gets quotes from them about their lives and it's pretty inspirational. And he actually went to Europe, to Syria and to Greece to watch the Syrian immigrants come and spent weeks telling stories of these individual families...

GJELTENMm-hmm.

GOLBECK...and what they were escaping. It was extremely powerful. Even though we were hearing about the refugee crisis, we were seeing these dramatic pictures, to actually hear individual people and how they were burned out of their houses, they were forced to flee in the middle of the night, here's all the family members they lost, you suddenly saw a much realer picture of what was going on. And though I was very sympathetic to that in the first place, it had a very dramatic impact on me. And I think that's an example of one way that social media can be largely used to really humanize something.

GJELTENMm-hmm.

GOLBECKBecause social media is different than all other platforms in that it allows you to broadcast but also interact, right? On the radio you can broadcast but it's hard to interact. You can have a one-on-one conversation. Social media gives you both. And it's a way that can help you build a lot of empathy and understand what's otherwise just other people, right? You see the humanity in them. And that, I think, can counter a lot of this.

GJELTENJennifer Golbeck is associate professor in the College for Information Studies at the University of Maryland. I'm Tom Gjelten. You're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Paul Rosenzweig, let's bring you back into this conversation. So in the case of the San Bernardino shootists, let's go back to that. Tashfeen Malik posted a declaration of allegiance to ISIS on Facebook. That post was then immediately taken down. What was accomplished by taking that post down?

ROSENZWEIGVery little at that point. I mean, she -- as I understand it, she posted just before the attack. And so taking it down is merely an expression of disregard or dislike by Facebook, you know, a disassociation of themselves. So they do it for their own political reasons. It would be interesting -- to pick up on something Lorenzo had said -- to imagine if that post had, say, preceded the attack by a week or by some unknown period of time. The post comes up, somebody declares bayat to ISIS, the loyalty. What is really the right set of responses to that at that time, when the attack isn't 20 minutes later but some unknown period of time.

ROSENZWEIGI tend to agree with Lorenzo that the right -- that takedown in that instance is the wrong reaction. It's much better as an intelligence tool. Takedown, for me, to the extent that companies do it or the government compels it, is really for things like the beheading video of James Foley.

GJELTENMm-hmm.

ROSENZWEIGOr the burning video of the Jordanian pilot. These really horrific images that are designed essentially to shed terror. And that, yeah, I don't know, maybe Lee would disagree. But I think even she would probably agree that there -- that that speech, that we could rightly remove from the public sphere.

GJELTENWell, Lee Rowland, let's go to you on this. That actually -- it takes us in a little bit of a different direction. Because Paul raised the scenario of somebody posting allegiance to ISIS before they carry out an attack.

ROWLANDRight.

GJELTENWould that justifiably trigger surveillance of that person by law enforcement agencies? If they see something like that, is that, you know, would that be just cause to begin a pretty intensive surveillance of that person's communications at that point?

ROWLANDWell, I think it's pretty important to be clear about what we mean when we say surveillance, right? I mean, when someone is posting on social media, they don't have an expectation of privacy, right? They are posting it for it to be seen. And here, in the case of Tashfeen Malik, it seems like the timing of that indicates that she wanted it to be seen, right? Just perhaps post-facto. But when somebody is speaking out in public, it would be like an officer seeing something on the street, right? So, of course, I think the average law enforcement officer made aware of that speech could and would follow up on that with public investigatory tools.

ROWLANDNow, I think the tougher question and the question that undoubtedly would be more controversial both among the public and, I'm guessing, members of the panel, is whether or not simply pledging allegiance to a group, standing alone, would be enough to support a legal process like probably cause. And, you know, in my view, the answer would tend towards no. That facts, you know, something like probable cause tends to be a set of facts and circumstances that are fairly specific. That is how the criminal justice system works.

ROWLANDAnd if you were to look in to that person and, based on publicly available information, had other indicia that the person had weaponry, had, you know, had a combination of factors involving, say, travel and communication with known terrorist entities, absolutely, put together, that might establish a level of suspicion that reaches probable cause. But I think suggesting that we are going to turn a simple expression of opinion -- again, no matter how objectionable or offensive -- into a substitute for probable cause for law enforcement, is very troubling and something we don't do and we shouldn't do.

GJELTENLee Rowland is senior staff attorney at the ACLU's Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. Paul Rosenzweig is shaking his head across the desk here. After this break, we're going to give him a chance to respond. He is principal at Redbranch Consulting and a former deputy assistant secretary at DHS. We're going to take a short break here now. Stay tuned. We'll be right back.

GJELTENHello again, I'm Tom Gjelten, sitting in for Diane Rehm. We're talking about the use of social media by ISIS and other terrorist organizations and what, if anything, we can do about it. My guests are Jennifer Golbeck, she's a computers scientist at the University of Maryland, Lorenzo Vidino, who is director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, Paul Rosenzweig, he used to be assistant -- deputy assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Homeland Security, and on the phone from New York, Lee Rowland, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU.

GJELTENAnd just before the break, Paul, Lee was saying that declaring allegiance to ISIS is in fact a form of speech, and you were shaking your head at that point.

ROSENZWEIGIt's obviously a form of speech. The reason I'm shaking my head was that...

GJELTENBut it's not just a form of speech.

ROSENZWEIGIt's not just an opinion. I mean, if you understand ISIS, declaration of bayat is not just a form of allegiance, it's a form of commitment to action. It is a swearing of fealty. It's kind of like taking omerta with the Mafia. It is more than that. So my disagreement with Lee would've been that I think that that's ample probable cause for an investigation.

GJELTENAnd if I'm not mistaken, according to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the head of ISIS, he actually tells his followers to swear bayat before they undertake an action. So this wasn't just a casual thing by Tashfeen Malik. She was following instructions, in a sense.

ROSENZWEIGIt's a precursor to action. I mean, if the post had been I think that America stinks or something like that, I'd be with Lee completely. It's just that I think bayat's very different.

GJELTENAll right, Lee, we'll get back to you in a minute, but I want to bring some listeners into this conversation. David tweets, how does the U.S. approach to monitoring social media content compare to other countries, where that content may originate? Lorenzo Vidino, do you have a thought on that?

VIDINOI think to some degree actually the U.S. has been more aggressive abroad because of our less limitations of what it can be -- can be done. I mean, we don't need to go back to the NSA activities and the Snowden case and how much we talked about it. I think the U.S., the intel community in the U.S. has more limits to what it can do domestically than abroad, and this is some of the issues that we are facing now with the ISIS mobilization, where, as we were saying earlier, there are not a lot of these links to abroad.

VIDINOIf, paradoxically, there had been more communication between the San Bernardino shooters, for example, and people abroad, and we don't know exactly, of course, who they were in touch with, that would've been easier for the U.S. intelligence community to detect. When it's more domestic, it's, for understandable reason, for the constitutional reasons, much more difficult for the U.S. to intercept. So that's the big challenge.

VIDINOThe big challenge with law enforcement faces exactly that. There's a much larger number of people, compared to the al-Qaeda mobilization a few years back, within the U.S. who are attracted to the ideology. They are active online. Most of their activities are protected by the First Amendment. All that law enforcement can do is monitor. But there are of course some sever legal limitations in what they can monitor and some manpower limitations. You know, you can't -- you know, even the FBI does not have the personnel to monitor the thousands of individuals that -- that's according to the director of the FBI, thousands of individuals who are attracted to ISIS ideology.

VIDINOMost of them are kids, just talk. Some of them are not. Again, how do you exactly assess who's all talk and who's not? So from a manpower point of view, that's the big challenge that this mobilization presents to the FBI.

GJELTENYeah, well, especially if 400 hours of video are being loaded to YouTube every single minute, that represents a huge challenge. Jen, I want you to respond to a very interesting question from Mike in Flushing, Michigan. He says, if would-be, aspiring terrorists can easily find these websites, why is it so difficult for the authorities to find them?

GOLBECKI don't think it is, actually. I think the authorities know about all of these websites, but there's not a lot that we're able to do about them, right? They're protected speech. And it's not just terrorism. I spend a lot of my time digging through the bottom of the barrel of the Internet, whether it's trolling these pickup artist sites, certainly terrorism. There's so much really terrible, objectionable, awful things out there online that we know about, but what can we do about it. It's protected speech, even if it's deeply objectionable speech.

GOLBECKI think these websites are being monitored. As Lee mentioned, it's all public. There's nothing wrong with that. So we know it's there. The question is, you know, if we have an example where you post a pledge of allegiance to ISIS right before you take an action, there's just too much for us to monitor it on a minute-to-minute basis and then react.

GJELTENYeah, yeah. Let's go now to Jonathan, who is on the line from Rockville, Maryland. Hello, Jonathan, thanks for calling "The Diane Rehm Show."

JONATHANGood morning, thank you for having me. As much as I have listened to this study, and I quite like it, it actually brings (unintelligible) but I also wanted to ask your guest there that how -- what's the relation? Because it seems as if everybody who's -- who actually finds themselves reading or following the likes of ISIS and other church organizations or people who probably have too much time on their hands and have nothing to do, are people who seek fame.

JONATHANAnd now having said that, I want to bring to light, and I want to see what you think about the way the media, the news, reports on such attacks such as the unfortunate incident in San Bernardino (unintelligible) why that -- why do they dedicate so much time to this because I've seen that's how -- that's actually something that plants thoughts or things in people's minds, that well, if these people are getting this much exposure, then I could be famous if I do this. And, you know, social media is actually full of people who are seeking attention...

GJELTENOkay, Jonathan, that's a really interesting question, and Paul, actually Jonathan has touched on a question that other people have raised, too. Robert wrote an email saying if news of bombings or shootings wasn't so widely advertised, the very concept of terrorism would fail. So this is -- this is a legitimate question.

ROSENZWEIGWell, it's got two parts to it. I mean, the main problem is that it's not just the news media who are publicizing this. This -- the single difference about social media is it allows you to be a self-publicist. It used to be that if you could get the New York Times to downplay an incident or something like that, it would not garner that publicity, but we don't have that control anymore. ISIS can self-publicize.

ROSENZWEIGOne of the things, I mentioned James Foley earlier, who is a fellow I actually know from Northwestern who was beheaded by ISIS, and his family has been fighting the beheading video everywhere it pops up and asking people to replace it with a picture of him smiling and saying hello and with only -- with incomplete success. It's just not doable to downplay the distribution at this point because we no longer -- we, the media, no longer control the distribution network.

GJELTENBut the question is whether -- is there a role here or a responsibility for mainstream media to, you know, every time that we, like, highlight all this stuff, are we adding to the problem, are we contributing to the problem?

ROSENZWEIGAre you not going to cover the death of 14 people in San Bernardino? I mean, or the six coordinated attacks in Paris? The media is in a difficult spot, and it, too, just as we've been discussing with Twitter and Facebook, it too doesn't really want the role of being the editor.

JONATHAN(unintelligible)

GJELTENLet's go to Philip now, who's on the line from Boynton Beach, Florida. Hello, Philip.

PHILIPHi, thank you guys so much for having me on the show. I'm so grateful for the service that you guys are doing, bringing this topic to the air. Sometimes that I wanted to point out, I read online an article that said that a university was able to do a study and show that they were able to determine whether people from the Middle East were supporters or opposed to ISIL based on how they referred to the organization. If they refer to it using its full name, you know, the full Islamic State, so on and so forth, and 98 percent of the time it turned out they were supporters of ISIS. If they refer to it as ISH, or however you pronounce it, which in Arabic means to be stomped on, then they turned out to, 98 percent of the time, not be supporters of ISIS.

PHILIPThere are algorithms that we can employ on social media platforms that are able to identify and flag supporters of ISIS to be looked over by human beings with closer scrutiny.

GJELTENLet's put that question to Jennifer Golbeck.

GOLBECKSort of, right. So it certainly could be the case that in particular communities, you do see this very clear distinction, if you use one term, it means one thing about your support and otherwise. But for example that certainly wouldn't apply here in the U.S., where I think most of use ISIS. I certainly use ISIS as a term to refer to them, and I am definitely not a supporter, right. This is an issue that we come up with with these kinds of predictive algorithms all the time, and this is where I do my research.

GOLBECKThey can certainly work in particular communities, but it's very hard to generalize them, especially generalizing them to the whole Internet because you do have these very cultural difference. And we've seen this not just in terrorism but in any place we try to deploy this. If you're looking at language and how people use it, the culture matters so much, little tiny bits of culture, not just I'm from the Middle East or I'm from the U.S. How people have been accustomed to use that language varies it.

GOLBECKSo the algorithms really are not at the point right now that we can certainly -- even -- I don't think we could even do better than random guessing overall, in terms of separating any person as ISIS supporter or not.

GJELTENReally? Lee, Matthew emails a question that I'm going to put to you. He asks, how is it that finding a way to stop prorogation of terrorism-supporting speech on online platforms is such a big issue, but no one seems interested in stopping the blatant anti-Islam things being said on these platforms? What is the line between hate speech and material support of terrorism, and why does it matter? As a defender of free speech, I'm sure you're very reluctant to go after even hate speech.

ROWLANDAbsolutely, and in fact hate speech is not -- you know, is a bit of a dog whistle itself. Hate speech has no defined class of words, right. Hate speech is frequently in the ears of the hearer or the eyes of the beholder, which isn't to say that as a free speech defender we can't also be human beings and recognize that there is a lot of speech that is incredibly hateful and hurtful and harmful, certainly emotionally.

ROWLANDBut I think the question really gets at, you know, really the underlying problem we're all wrestling with on this call, which is, yes, there are programs and algorithms and companies, assuming they're doing so voluntarily, who could probably get us closer to determining what speech we collectively agree is bad. But really that journey is already taking us down a rabbit hole in picking out good speech and bad speech. And we have always rightly been skeptical of allowing our government to do that, an asking private companies to do that betrays those same values.

ROWLANDSo you're absolutely right, and, you know, we started at the beginning of the hour with Jennifer talking, I think very smartly, about child pornography, right, something that is fairly objective. Right, we can identify an image and say this is or is not child pornography. The same is simply not true when we're talking about speech that we are calling quote-unquote hate speech or quote-unquote terroristic. So much of these words are on a razor-thin line between something that supports ISIS and is a totally legitimate opinion about foreign policy in Syria.

ROWLANDAnd so we just have to be so cautious in drawing these lines because once we do, we know we will sweep in more speech than we intend to, and that's true regardless of our motives, whether we're aiming at people we think are hateful, whether we're trying to capture hate speech, whether we're trying to capture terrorism. These are fraught decisions with immense amount of risk and immense of room for error for good speech, and that's just true. Censorship is a messy business no matter who's engaging in it.

GJELTENAnd that is the ACLU point of view from Lee Rowland. I'm Tom Gjelten. You're listening to the Diane Rehm Show. Paul, I'm going to give you -- you served in government, and I'm sure you had access to intelligence and discussed intelligence. We had a listener tweet, what about using human intelligence to infiltrate these social media circles in ISIS? Going about it sort of in an old-fashioned -- I won't say boots on the ground, but infiltration. Is that realistic at all?

ROSENZWEIGYes, it is. And indeed I'm reasonably certain that it's one of the tactics. It has had -- it by itself also raises some concerns, which is that any time the government starts to take an undercover role in the communication of ideas, people with free First Amendment concerns start to have some worries about that. But it is nonetheless absolutely the case that the government, in addition to trying to monitor the external face of this, is trying to get intelligence from the inside on what is happening, both from human intelligence and I'm sure from signals intelligence, as well. Indeed, to my mind at least, they'd be sort of derelict if they weren't.

GJELTENLorenzo Vidino, I want you to respond to a tweet from David. We've been talking about what the government can and cannot do in this regard, and of course in the aftermath of 9/11, we had a Patriot Act that really changed the rules on what the government can do. Is there a need, or are you expecting people might be talking about some kind of new Patriot Act or, you know, new legislation that would give government more power to deal with this -- these problems?

VIDINOI mean, we are in a presidential campaign. So it wouldn't be surprising. We've heard just yesterday some other proposals, which are significantly more shocking.

GJELTENPretty radical.

VIDINOYeah, pretty radical compared to just a new Patriot Act. I mean, they look like a mild thing. So we might hear, obviously, things like that. I think we have pushed the limits. We're in a very delicate phase where clearly there is a lot of issues of feasibility and some constitutional challenges to what more we can do. I go back to the point that it's more about manpower, really. The powers are there from a legal point of view. I think something, maybe compelling companies to do a bit more or be more proactive, we get into technical details, but I don't see anything sweeping and radically changing short of being against the Constitution.

VIDINOWhat I think could be -- and this is something that is being discussed within government, is using this space to counter the message. Okay, ISIS is on social media, so let's have the government, and most importantly civil society, be also active in social media, counter the message there. So you do see, for example, in some Muslim-majority countries or in Europe, government efforts, and as I said more importantly civil society efforts, to go inside this bubble of ISIS sympathizers online and counter their argument from a theological point of view, from an ethical point of view, from a moral point of view, and just give them hell, challenge their arguments, dismantle their very flawed arguments in support of ISIS.

VIDINOYou know, you're not going to convince everybody, but you will create doubt in the mind of some people there. It's an echo chamber, but it can be broken. And I think that's where the government could be probably more active, maybe not necessarily doing it directly, though the State Department is active, the State Department has Twitter handle called think again, turn away, where it tries to challenge that kind of propaganda online, with mixed results to be fair.

VIDINOBut I think it's more successful if you have civil society, Muslim community at the end of the day, as President Obama said the other day, being active there, potentially with some support from the government but going there and having the right arguments to compel young people from ever embracing that ideology.

GJELTENPaul Rosenzweig, speak very quickly here for the government. Can the government do this?

ROSENZWEIGNo, the government does it, but we do it very poorly. A recent study by Silicon Valley execs says essentially our counter-narrative efforts stink.

GJELTENPaul Rosenzweig is a principal at Redbranch consulting, he's a former deputy assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Homeland Security. And we've been talking in this hour about what, if anything, can be done about the way that ISIS and other groups use social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. It's a very big story.

GJELTENMy other guests were Jennifer Golbeck, associate professor in the College for Information Studies at the University of Maryland, Lorenzo Vidino, he's director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, and on the phone from New York City throughout this hour was Lee Rowland, she's senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. Thank you to all of you.

GOLBECKThanks.

ROSENZWEIGThanks.

GJELTENI'm Tom Gjelten. Thanks for listening. You're listening to the Diane Rehm Show.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.