Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

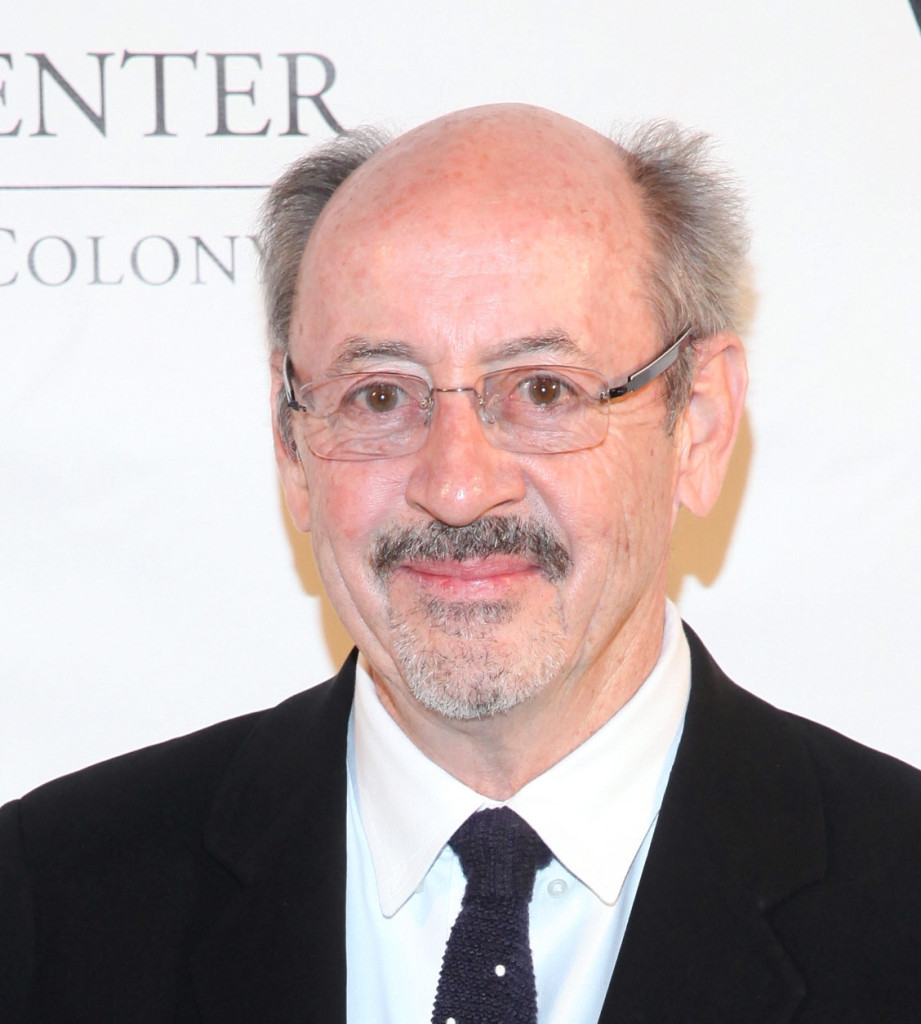

NEW YORK, NY - OCTOBER 27: Poet Billy Collins at the Sixth Annual Norman Mailer Center and Writers Colony Benefit Gala, October 27, 2014 in New York City.

Billy Collins has been called the most popular poet in America. The former U.S. poet laureate has used his success to help make poetry more accessible. Thanks to his efforts – you may have seen his poems on a subway car or bus. But Collins says most new American poetry has become too obscure. His own poetry is known for being unpretentious and humorous. His latest collection will likely please his fans. In one poem, he imagines sitting next to Shakespeare on an airplane, sharing earbuds. A conversation with Billy Collins about writing poetry.

Excerpted from THE RAIN IN PORTUGAL by Billy Collins. Copyright © 2016 by Billy Collins. Excerpted by permission of Random House, A Penguin Random House Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. Former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins is known for his playful and wise poems. He says poetry doesn't rhyme on purpose and the whimsical title of his new collection highlights this fact. It's called "The Rain in Portugal." Billy Collins joins me in the studio. You are, as always, invited to be one of our guests. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. Billy Collins, it's always good to see you.

MR. BILLY COLLINSVery nice to be here, Diane. Thanks for having me on.

REHMThank you. Oh, my pleasure. And congratulations on the birth of your brand-new book. You've got to talk about this title.

COLLINSWell, today's the birthday of the book. It was -- today is the pub date and I don't what sign it is. Maybe it's a Libra, I'm not sure. But...

REHMI think it is, yes.

COLLINSI'll have to see if the book and I are compatible according to the stars. Well, the title is -- I often title the book after a poem in the book, but in this case, it's really a line from a poem. And, you know, I'm not a rhyming poet, at least in the traditional sense of the word. I try to write with my ear and I try to write poems that sound good, you might say. And just to go back, I mean, this is a little historical, but when rhyme became an option in American poetry in...

REHMWhen was that?

COLLINSWell, it starts with Whitman in "Leaves of Grass." He was the first one to write a poem without end rhyme or regular meter. Shakespeare, of course, used regular meter without the end rhyme and blank verse, but -- and then, it really wasn't picked up until the 20th century. But what happened was -- and this is often a misunderstanding. Poets didn't just take scissor the rhymes off the right side of the poem and throw them out the window. In the best poetry, the rhymes, you might say, abandoned their little positions at the ends of the lines and invaded the body of the poem.

COLLINSThey went inside the poem and became a more organic part of its soundscape, you might say. At any rate, so I do write with the ear, but I don't have rhymes at the ends of lines, usually. So I wrote a poem on rhyme. I love formal poetry. I've been teaching English literature for over 30 years and there's a lot of great formal poetry being written today. But I -- and this poem on rhyme, I expressed my preference for un-rhyme poetry.

REHMUn-rhyme poetry.

COLLINSYeah, and I said, you know, I like Jack Horner sitting on a sofa, you know, and I've kept subverting some of these rhymes. And instead of the rain in Spain, I like the rain in Portugal. Not much rhymes with Portugal. So the title of the book, "The Rain in Portugal," is -- I wouldn't call it exactly a trigger warning, but it does imply to the reader that he or she is not in for a traditionally rhymed experience in poetry.

REHMI think that that aspect of un-rhyme poetry leads some people to wonder is a poem without rhyme truly a poem or is it simply a continuing narrative?

COLLINSWell, this became -- it is a question for people who haven't been paying attention to poetry, quite frankly, because it's become, as I said, an option in poetry. But I have encountered -- I was -- I gave a talk in England many years ago in a rather rural community and this then to be elderly man asked a question. And I -- his question was completely innocent. He said, Mr. Collins, are all your poems written in prose? And now, if this was delivered by Oscar Wilde, I would've been devastated, but he missed the little song.

COLLINSHe missed the little song that was really synonymous with poetry. I mean, regular rhyme and meter was the definition of poetry until this breakaway from it into what's kind of weakly called free verse.

REHMAnd yet, you proclaim that some of current modern poetry is not to your liking, that somehow it strayed too far.

COLLINSWell, this is not a recommended aesthetic. It's really just my taste after many decades of reading poetry. I mean, the fact is, I don't finish a lot of poems, reading poems and I think that's the case with a lot of readers. I mean, I'll read five or six lines or maybe two lines and in some cases, I'm out. There are just a lot of deal breakers. And I'll name two of them. Okay? One of them is just the poem is way too obscure to begin with. I don't mind obscurity and difficulty as the poem progresses and finds a way into a rather, you know, ambiguous or hazy situation.

COLLINSBut if it starts out with something totally mysterious and demanding, I feel we haven't been introduced yet, you know, the poet and I and it's a little too much too soon. I like poems that start in simplicity and end in complexity. So the way I sometimes put it is I like poems that start in Kansas and end in Oz. But I don't want to start in Oz, you know.

REHMYeah, yeah.

COLLINSIt's too much too soon. And the other -- so the other poems I don't finish or the type of poems are making -- are presumptuous of my interest in their personal life and usually personal misery. In other words, you really have to -- I always start with the indifference of the reader because I'm -- we're really -- poets are writing to strangers. We might show our poems to friends and family and colleagues, but basically, we are after what Roger Angel of The New Yorker called the love of strangers. He said writing is really about the love of strangers.

COLLINSAnd I try to -- in my poetry workshops, I try to introduce this as kind of task. I mean, how do you get a stranger to love you or at least be, you know, interested -- want to date you maybe for a minute or two in a poem. And there are techniques and ways of doing that. But one way is not to rush into the poem with a lot of emotional baggage. In fact, when I use the expression emotional baggage, I say to my students that you are allowed on carryon.

REHMAnd the airlines would totally support you. You know, you talk about formal poetry and the rhyme and the meter of, say, Shakespeare, and yet, you include Shakespeare in one of your poems. And I wonder if you would read that for us on page -- my page 29.

COLLINSSure. This is...

REHMAnd tell me what inspired this poem.

COLLINSThis is a little segue from air travel, right?

REHMYeah.

COLLINSWell, there's a famous line in Shakespeare that -- it's the fourth line of this poem, I repeat it. And I was on an airplane and I -- you know, often a poem starts where two things that have a lane very separate and parts of your mind somehow get synaptically connected. And that's what happened here. Excuse me. And it's called "The Bard in Flight."

COLLINS"It occurred to me on a flight from London to Barcelona that Shakespeare could have written This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England with more authority had he occupied the window seat next to me instead of this businessman from Frankfurt. Of course, after a couple of drinks and me loaning him an earbud, he might become too preoccupied with "Miles Davis at the Blackhawk" at 36,000 feet over one realm or other to write another word.

COLLINSI imagine he'd enjoy playing with my wristwatch, the one with the tartan band, and when he wasn't looking out the window, he would study the ice cubes in his rotating glass. And he'd take a keen interest in the various announcements from the flight deck and the ministration of the bowing attendants. All of which would be sadly lost on me having gotten used to rushing above the clouds, even though 99 percent of humanity has never been there.

COLLINSYet, I am still find of the snubbed nosed engines, the straining harmony of the twin jets, even the sensation of turbulence, jostled about high above some blessed plot with the sound of crockery shifting in the galley, the frenzied eyes of the nervous passengers and the Bard reaching for my hand as we roared with trembling wings into the towering fortress of a thunderhead."

REHMBilly Collins reading a poem titled "The Bard in Flight" from his newest book of poetry titled "The Rain in Portugal." Billy Collins is, of course, the New York Times bestselling author of "Aimless Love" and many other books of poetry and the former Poet Laureate of the United States. Short break, right back.

REHMAnd welcome back. Former Poet Laureate of the U.S. Billy Collins is with me. His newest book of poems is titled "The Rain in Portugal." He's not so keen on rhymes throughout his poetry. So instead of the rain in Spain, we have "The Rain in Portugal." I love the cover. Explain the cover.

COLLINSWell, I've been lucky enough to pick all my cover art. I don't know why the art department at Random House lets me do this. I always feel it's a little like going into the kitchen at a restaurant and saying, putting some soup in the -- I mean salt in the soup, and some guy running after you with a cleaver.

COLLINSBut I think I'm actually pretty good at it. But I really just surf the Internet to find images. And in this case, I was hard pressed. I really hadn't found an image and it was time to deliver one. And I just -- I found this image. It's a little drawing by a 18th century French artist called Coypel, Charles-Antoine Coypel. I'd never heard of him. And it's a drawing of a woman with a look of I don't know what, anxiety?

REHMQuizzicalness?

COLLINSTroubled, a quizzicalness.

REHMYeah. Yes.

COLLINSSomeone -- a friend of mine told me that -- my dear friend Susanna told me that she thought the woman's expression was caused by her trying to figure out what the heck the title means. But -- so she's looking off...

REHMIt works.

COLLINSShe's actually a figure from the Bible. She's the wife of a fellow named Potiphar, who was -- and I'd never heard of him either, quite frankly. But she's not a nice lady as it turned out.

REHMOh, really?

COLLINSI didn't know the story so I'm innocent of her doings. But she apparently -- she's famous for trying to seduce a friend of her husband's. And then having been rejected, accusing him of rape. So I'm sorry if it ruins the cover for you.

REHMWow.

COLLINSThat's not the kind of...

REHMThat's quite a story.

COLLINS...not the kind of subject that usually finds its way into my poems.

REHMYou have said, elsewhere, that the stuff coming out of a Master's of Fine Arts program is not great. That these poems become too cloyingly personal. You've already mentioned that. But what is it about those programs that you think has gotten these scholars, students off on the wrong foot?

COLLINSWell, I don't think they're terribly -- there's anything intrinsically wrong with, again, a course for an MFA. At the very least, you'll be able to read poetry better. I remember taking an oil painting classes a long time ago, not to be a good oil painter -- because I don't even do it anymore -- but to understand oil painting better. But I do think that the imbalance I guess or the misperception is that you can be taught by a senior poet sitting at the end of a seminar desk and a series of those poets.

COLLINSI think the real teachers of poetry are on the shelves of the library in the anthologies. I think it's John Donne and Emily Dickinson and Wordsworth and W. H. Auden and X. J. Kennedy and Miller Williams and Ron Padgett and I could name 150 other poets. I think that's how you learn, not so much sitting around and comparing each other's work. I'm also just too old for that. I mean when I say that I mean, when I came out of a college in 1963, it should be said, there were no such thing as MFA programs. There was -- I think there were two actually, one at Stanford and one at Iowa.

COLLINSBut, you know, it would be thought, as going into periodontal school, I mean something very, you know, you'd never consider, or I wouldn't. And -- but the reason I got into poetry as a teenager was, it had to do something with -- it had a lot to do with being alone. In fact, poetry was something you did with your aloneness. It's a way of -- just you and the language. And there was that kind of intimate relationship between your expressive desires and the English language. And now it seems to be that it's kind of a quilting bee. I mean people are helping each other, encouraging other, and giving feedback. And there's probably too much revision going on.

COLLINSBecause what can you say about a poem in a class? It's perfect? Put a stamp on it? Send it to the bureau of engraving? I mean, I've done that occasionally but it's rare. No, you say -- excuse me -- it needs more work. And so often, if the revision process becomes too continuous or endless, it -- you lose that initial impulse in the poem. And I don't mean that first thought, best thought, that you should, you know, just get high and be spontaneous. I mean, you should write with deliberation and care. But you can kind of sap the juice out of the poem by (word?)

REHMHow do you think that differs from the editing process in, say, a novel or a memoir?

COLLINSWell, there I think -- well, you know, it brings up the whole status of editors these days. I mean, there are -- I think the days of William Maxwell and Maxwell Perkins and editors like that, who were almost co-writers in a sense. I mean they really took sentences and changed them around. And they were -- today, would be thought to be kind of intrusive or invasive. But I don't know, usually editors -- I've never gotten a line edit. And I think that's true of other editors. No one's ever come in -- except very occasionally and helpfully -- and said, we need to change this stanza all around. Or the fourth stanza should be the first stanza.

COLLINSWith my editor, David Ebershoff, Dan Menaker and Andrea Walker -- I've had some really great editors at Random House -- I give them 70 poems, say, too many for a book. And I just say, find the weak ones.

REHMHmm.

COLLINSFind six or eight weak ones.

REHMHmm. Hmm.

COLLINSAnd then we pare it down that way.

REHMBob Gottlieb has been my editor since 1998.

COLLINSLucky you.

REHMOh, you bet. And exactly as you say. I mean, it's barely touching, it's barely -- simply emotionally providing the support I've needed to write.

COLLINSYeah. That's true of a good editor I think. They're -- you get a sense that they are in your corner and you're both -- if they're not co-writing the book with you, they're co-giving birth to it or something. They're...

REHMAbsolutely.

COLLINSYeah. It is a joint effort, emotionally.

REHMTell me about what you see is the difference between public and private poetry language and getting into, of course, today everybody is talking about politics and how that enters the poetical...

COLLINSMm-hmm.

REHM...image vision.

COLLINSWell, I think of poetry as a private language. And I think of it as a very intimate language. And I think one of the uses or usefulness as -- of poetry or one of the pleasures it offers, or -- is that it provides a kind of refuge from the, you know, the din of public language. And public language, whether it's a political speech or advertising, it's -- you get the sense that you're being spoken to as a mass, a part of a crowd. And in good poetry, I think, or in some poetry -- Whitman is a great example of creating intimacy -- you really feel like there's one person speaking to you.

COLLINSAnd, you know, back in the -- I guess it was in the '40s, George Orwell wrote this very important, lasting essay called "Politics and the English Language." And he pointed out, even then, which kind of rings true of today, that the trouble with political language is that it really is hiding the truth. It uses euphemism and things like relocation or ethnic cleansing, where -- kind of covering the truth of what's going on. And he says that if you really said the truth, it would be too brutal. So there's this way of being insincere. And he then gives some kind of guidelines for more direct writing.

COLLINSBut he feels that if the language becomes contaminated with euphemism and lying and indirection, it affects our thinking, we -- if we're not -- if that's the language we're exposed to and we begin to think that way.

REHMWe have a number of calls. But before we open the phones, humor really has been your trademark. And you have a very funny poem about dogs on page 27. And it's called "Species." And I happen to have a dog I love deeply. So I'd like you to read that poem.

COLLINSBe happy to do that. Well, I'll dedicate it to your dog.

REHMMaxie.

COLLINSTo Maxie. "Species. I have no need for a biscuit, a chewed toy or two bowls on a stand. No desire to investigate a shrub or sleep on an oval mat by the door. But sometimes, waiting at a light, I start to identify with the blonde Lab, with his head out the rear window of the station wagon idling next to me. And if we speed off together and I can see his dark lips flapping in the wind and his eyes closed, then I am sitting in the balcony of envy. Look at you, I usually say, when I see a Terrier on a leash trotting briskly along as if running his weekday morning errands. And I stop to stare at any dog who is peering around a corner, returning a ball to the thrower or staring back at me from a porch.

COLLINS"So early this morning, there was no avoiding a twinge of jealousy for the young Spaniel tied to a bench in the shade, who is now wagging not only his tail but the whole of himself, as a woman in a summer dress emerged from the glass doors of the post office, then crouched down in front of him, taking his chin in her hand and said in a mock-scolding tone, I told you I'd be right back, silly, leaving the dog to sit and return her gaze, with a look of understanding which seemed to say, I know, I know. I never doubted that you would."

REHMAh. That's just lovely. I really...

COLLINSThanks.

REHM...enjoyed that. And I'm going to go to the phones, to Greg here in Washington, D.C. You're on the air.

GREGThank you, Diane. And thank you Mr. Collins for your poetry. I love listening to you. A friend of mine went to one of your workshops and said you discourage your students from using a lot of adjectives. And I try to write serious poetry and I found that very challenging and wondered if you could say more about that?

COLLINSSure. I probably quoted Emerson, who talks about the speaking language of things. In other words, that actual objects and particularly objects in nature are already talking to us. And I just find in -- very refreshing to read Japanese and Chinese poetry, especially earlier works of the 17th, 18th century, where there's just the tree, the bridge, the river, the pot, unadorned. And these objects take on a kind of integrity if you don't cover them in adjectives and other modifiers. So I just try to keep it simple. These objects, if you have any reverence for them, don't really need you to decorate them. They're find just as they are.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." I wonder, however, whether you would agree with Greg that perhaps unadorned nouns make it a little more difficult to write poetry?

COLLINSWell, it depends on what kind of poetry we're writing. And it should be said, at some point, Diane, that we're using this word poetry, which is a very slippery -- not so as much slippery but a very broad word. It's almost like -- I like to compare it to the word sports. You know, if you had -- let's say you had on your -- you wouldn't have on your program that had the theme of sports, a badminton player, someone from the NFL and an Olympic swimmer. I mean it...

REHMTogether.

COLLINSTogether, right?

REHMYeah. Right.

COLLINSAnd had them talk about this thing called the, you know, the sport -- the future of sports in America. But there are so many widely different verbal activities that go on under the umbrella heading of poetry that you could get three poets into your studio that would be -- that have as little in common with each other as those three athletes. So there is interesting, highly decorative poetry that's lush and full of sound effects. Gerard Manley Hopkins comes to mind.

REHMAha.

COLLINSJust amazing.

REHM"The Windhover."

COLLINSOf textural language that you can feel in your mouth and hear in your ear. I just go -- I'm on a different kind of aesthetic. I love the poet Charles Simic, who writes with the most simple diction. And -- but also, if you have a simple diction and unadorned nouns, once you deploy and interesting adjective, once you throw in a word like luminescent, it stands out against the background of that simplicity.

REHMYou must have encountered a variety of poets and poetry as the poet laureate.

COLLINSWell, even before that. But, yeah, I mean, that's really the beauty of it, the variety of it. There are so many...

REHMDid you enjoy that year?

COLLINSI enjoyed -- for -- yeah, I mean, partly. I enjoyed the -- it was good for my self esteem for one thing. Because you're the lead dog in American poetry for a couple of years. And I was quite honored by it, you know, quite frankly. You'd have to be. But I did feel kind of drawn away from where I write by having a lot of public duties. But that's not to complain.

REHMBilly Collins, former U.S. Poet Laureate. His new book of poems is titled, "The Rain in Portugal." Short break here. Your calls, comments, when we come back. Stay with us.

REHMWelcome back. Billy Collins is my guest. Of course he is a former U.S. poet laureate, a title bestowed on him and which he took very seriously, both the honor and the responsibility. In fact you became involved in this Poetry in Motion project. Tell us about that.

COLLINSWell that predated my laureateship, but I continue to be involved in it. I'm on the board of the Poetry Society of America, and we're the ones who came up with the whole idea of Poetry in Motion, that is to say putting poems on public transportation, buses and trains and subways. And that still continues. And I think the whole -- I mean, another thing I did was when I was poet laureate, I started a poetry channel on Delta Airlines. I got them to agree to that, somehow. I was really determined to do that, and I found out who does that and talked them into it.

COLLINSAnd I would -- we'd pick a theme, like birds or music or love, and I would pick the poems, not my poems, but I'd read them, and then we've had a little jazz in between. So if you were on the -- on an airplane, and you didn't want to hear music or a movie, you could actually listen to poetry, and that lasted a couple of years.

REHMGood.

COLLINSSo I'm all for poetry in public places, getting poetry out of the library, out of the classroom, off the bookshelves where people tend to sequester it and into public life.

REHMHere's a tweet from Johnny. I'm curious if your guest has any thoughts about the format of Twitter as an avenue for poetry.

COLLINSWell, let me tweet right back to you, Johnny. Well interesting, it's 140 characters, is that right? And there are actually 140 syllables in a sonnet because a sonnet is 14 lines long, and it has 10 syllables per line. I met someone who knew the guy who started it and said there's no connection there whatsoever, but there is a connection. The postcard, the haiku, the sonnet, all of these -- and the tweet, all of these limit, give you a limited space in which to work.

COLLINSAnd that's one of the pressures of poetry, if you're writing formal poetry, a sonnet or a pantoum or a villanelle. And so it is a compression. You have to think before you write, or you should think before you write. Now there's that famous line of the guy writing his son and saying I'm sorry I wrote you such a long letter, I didn't have time to write a short one because you have -- you can't just go on and on.

COLLINSSo there is -- they do have in common, tweeting and poetry, the idea of interesting things happen under compression.

REHMHere's a caller in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Billy, you're on the air.

BILLYHi yeah, Mr. Collins, first I want to say that I have three books of your poetry, I think your poetry is intelligent, insightful, humorous and poignant. And I have a question, but I don't think it's really a question. Maybe you're already answered or don't even care to answer. But, you know, I've found over the years that of people who have -- you know, some people that seem kind of elitist, who seemed embarrassed to say that they liked a Billy Collins poem. And it dumbfounded me, and I wondered if it was jealousy. And then I know you talked about there's all kinds of poetry, and it's a subjective thing what people like.

BILLYBut I was wondering what you think that essence is, like you said, well, you like poetry that just speaks, that has very few adjectives. But then what is it, then, that some people can -- that lots of people whose poetry is wonderful, they break all the rules, let's say a Bukowski or then the people that use lots of adjectives, and yet there's something there? What is that essence that makes that poetry so beautiful and good?

COLLINSWell that's an interestingly layered question. That last question is interesting, that -- what, if you get rid of regular rhyme and meter, and you get rid of a sort of lush language, what is there left that is poetry? And the only thing I can say is it's some kind of authenticity of voice. I mean, like Bukowski, you believe in him. You know, even though his -- the life he's describing is quite extraordinary or unusual, you buy in, and I can't judge that.

COLLINSI mean, one of the things we lose when we do lose regular rhyme and meter is a system -- rhyme and meter -- is a system of trust because a formal poet will never let you down. You know, Frost, if he starts out, whose woods these are I think I know, he will continue that beat and those rhymes to the end. So you can -- there's a trust system there, and the loss of it means that we have to compensate for that loss through something called authenticity of voice, and that's very hard to describe, but you know it as soon as you read it.

REHMTo Jesse in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Hi there.

JESSEHello, Diane, thank you so much for having me on.

REHMSure.

JESSEAnd I just wanted to let you it's never too late to become a constitutional scholar.

REHMThank you.

JESSEBilly Collins, I hope, will be referred to as poet laureate emeritus. There's something just unseemly about the former poet laureate.

REHMOkay, I hear you.

JESSEI don't know if that's really a title he can have, but if I could bestow it upon him and maybe start a trend there. Every time I hear his name, I like to tell a story about the only time I saw him, which was at an event here in Santa Fe almost exactly 15 years ago, and it was so shortly after 9/11, and he spoke to an enormous room, and it was really touch and go.

JESSEThis was just a couple weeks after September 11 in 2001, and you just -- you saved it for everybody. You just let everybody exhale, and it was so important. And...

REHMI agree, Jesse, and clearly so important to you. I can hear the emotion in your voice, which clearly you had conveyed to Billy Collins. Do you remember that day?

COLLINSNo, I don't actually. It's quite -- I'm very moved by his being moved by it, and I thank him for those words. I remember having to travel a lot right after 9/11. I remember being in Santa Fe, but I don't remember the actual experience or the emotional tenor of it.

REHMWhat was that like for you, traveling after September 11?

COLLINSFrom September 11 to I think the first week in December, I was on 37 airplanes.

REHMWow.

COLLINSAnd one of them landed in -- I'm fine with flying, but one of them landed in San Diego, and if you've ever landed there, you actually, you -- the flight path takes you right through downtown, and the office buildings are higher than you are, and you can see people working at their desks. There was -- a deep stillness fell over the airplane because here was the confluence of aircraft and skyscraper quite close to each other. Otherwise I was fine, but that was -- that was a little scary.

REHMDo you remember the emotional reaction of the audiences during that period of time?

COLLINSWell, everyone was still very aware of it. I mean, my real reaction to 9/11 was caused by being asked by Congress, because I was poet laureate, to write a poem on the first anniversary of 9/11, when Congress met jointly in New York City, historically almost unprecedented. And I did write a poem called "The Names," which I recited in front of Congress, which was a good example of public and private language, actually, because there had been a lot of speeches before my poem came up.

COLLINSAnd, you know, there -- everyone was quite sincere, and it was sometimes moving, but it was kind of the language of the -- the language of public language, heroism and the nation and that kind of thing. And my poem started with an image of rain at night, and the congresspeople looked up like they had heard something strange, like a whistle to a border collie or something, and they didn't -- suddenly they realized it was poetry.

COLLINSBut it really pointed out the difference between -- it was a very distinct change of verbal equality and mood that took place there, not to compliment the poem just but to point out the palpable difference between the private language of poetry with imagery and more abstract language of politics.

REHMAnd an email from Margaret, who says I've always found the flow of your phrasing to be almost stream of consciousness. Can you tell us about your method of writing, editing and finalizing your poetry?

COLLINSWell, it's stream of consciousness with about 10 revisions. It's not any -- I mean, you know, we -- Yeats said this, too. We labor to sound spontaneous. I mean, it takes work to sound convincingly spontaneous. So most of my poems are written in one sitting, kind of that's the run of the poem from beginning, middle to end, and when I do go back, it's not so much revision as refining it, refining the sound and the cadence of it.

REHMWhat about poetry at marriages, poetry at funerals, poetry at staged events?

COLLINSPoetry after 9/11, yeah. I mean, we -- after 9/11 people said we turn to poetry, you know, we turn to poetry at these times, implying that people have had their backs to poetry all this -- all the other times. So a poem comes up at a wedding or a funeral or a tragic event as a stabilizing factor, I think. It's something people can even memorize, but because of its form, it tends to stabilize emotion and honor it and also connect you with the past.

COLLINSYou can read a poem that was written two centuries ago at a funeral or a wedding and realize that centuries of human beings have felt the same way.

REHMTo Barry in Ashburn, Virginia, you're on the air.

BARRYHi, I've got two questions that are unrelated. First is, and I'm kind of an ignoramus when it comes to poetry. I'm trying to understand the difference between blank verse and prose. Is there some sort of dividing line? I think he may have touched upon this a little bit in what you were saying earlier with respect to some poet that's a little more difficult to read.

COLLINSCan I tell, can I...

BARRYIs it just that you know it when you read it?

COLLINSNo, well blank verse is a term in English metrics. It means unrhymed iambic pentameter, so ba-dum-ba-dum-ba-dum-ba-dum, five of those, and it's not rhymed at the ends of lines. And prose doesn't have to pay any attention to that.

REHMAnd you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show.

BARRYMy second question?

REHMBarry you had another question about "Jabberwocky."

BARRYYes, why do we -- I love that poem, and all the words in it are completely made up. Why do we like it despite its...

REHMWackiness.

BARRYKind of understand it even though the words are undefined.

COLLINSWell, it's pure language fun. I mean, it sounds like, 'twas brillig, I mean, it actually sounds like brillig should be a word, so it's not complete nonsense because it's following English syntax. You know, it's sounding like a sentence, but the words don't make any sense. I don't know, it's pure joy. It's like the joy in rock 'n' roll when someone sings be-bop-a-loo-la or koo-koo-ka-joo, or it's language that -- you know, there's so much play involved in language.

COLLINSI mean, we've defined poetry as things like opening our hearts and memories to the encounter the world, I'm quoting from the New York Times. But it's -- in writing poetry it's pure self-entertainment, it's pure fun, and that's just language. In "Jabberwocky," language let loose in a dog park to kind of, you know, just run around and collide into each other.

REHMNow here's a tweet from Donald, sorry from Ronald, who says, I love listening to poetry, but I have a hard time reading it. What is the secret to reading poetry?

COLLINSWell, when you hear it, you usually are not alone. And reading it, maybe the caller is experiencing a difference between being alone and being with other people. You can try reading it out loud, but it takes, it takes some gift to read poetry out loud, actually. I would say when you're reading it, just try to read it in your head. You know, another poet pointed out that the skull is kind of an auditorium. When we're reading silently, we're actually hearing it, you know, silently hearing it, if you will.

COLLINSI don't know, I would rather read it alone than hear it, myself.

REHMWould you read for us one last poem of your choice as we close?

COLLINSWell, let me -- this little poem called "December First," and I'll just tell you my mother's maiden name was -- they were from Scotland or from the Hebrides, was McIsaak, I mention that. December First, today is my mother's birthday, but she's not here to celebrate by opening a flowery card or looking calmly out a window. If my mother were alive, she'd be 114 years old, and I'm guessing neither of us would be enjoying her birthday very much.

COLLINSMother, I'd love to see you again and take you shopping or to sit in your sunny apartment with a pot of tea, but it wouldn't be the same at 114, and I'm no prize, either, almost 20 years older than the last time I saw you, sitting by your deathbed. Some days I look worse than yesterday's oatmeal. Happy birthday anyway, happy birthday. Here I am in a wallpapered room, raising a glass of birthday whiskey and picturing your face, the brooch on your collar.

COLLINSIt must've been frigid that morning in the hour just before dawn on your first December first, at the family farm 100 miles north of Toronto. I imagine they had you wrapped up tight, and there was your tiny, pink face sticking out of the bunting, and all those McIsaaks getting used to saying your name.

REHMBilly Collins, poet laureate emeritus.

COLLINSThank you, Diane, for having me on your program.

REHMHis newest book is titled "The Rain in Portugal." Thanks all for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.