Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

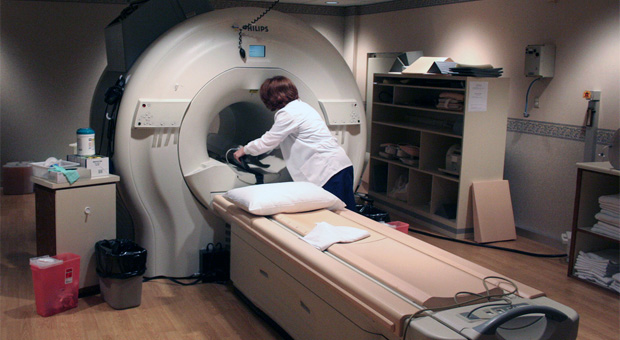

With healthcare costs in the United States ballooning, some are calling for restraint in the prescription of expensive medical tests like MRIs.

Doctors order and patients request many medical tests that add to expenses without improving care. A number of medical and consumer groups are now recommending doctors think twice before routinely prescribing some common medical tests such as stress tests for people with no symptoms of heart trouble, MRIs and CT scans in the early weeks of back pain, and routine colonscopies more than once a decade. Please join us for a discussion on the kinds of medical tests some say we can safely skip and why.

Most of us get medical tests we don’t need. That’s a fact recognized by almost everyone in the health care field. Last week, some medical and consumer organizations

issued guidelines about tests we probably should skip.

Some Common, Unnecessary Tests

“Some of the tests that have been noted are things like CT scans or MRI scans of the head after an uncomplicated fainting spell without any other symptoms, an annual cardiac stress test for a person who has no sign of cardiac disease and no risk factors, or routine chest x-rays or EKGs as part of an annual physical or before outpatient surgery or minor surgery, and then a very common one is MRI of the spine within the first six weeks of the onset of lower back pain,” Cassel said. Brownlee said unnecessary care is actually quite a large problem, with anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of all care delivered in the U.S. estimated to be unnecesasary care.

Some Tests Are Money-Generators

Some doctors are more likely to order certain tests more often than may be necessary because the tests are revenue generators. For instance, Dr. Mishori said he has seen patients who have visited a gastroenterologist who have told them they need a colonoscopy once every five years, when his own recommendation would be for the average patient with no other risk factors to undergo the procedure once every 10 years. Dr. Mishori also said, on the other hand, that he’s encouraged by some societies of specialist doctors that have spoken out against over-testing and procedures.

“Life Is Pre-Death”

Dr. Mishori said one of the other problems is that doctors often treat patients and order extra tests for even “borderline” conditions. “So now, we’re treating pre-diabetes, we’re now treating pre-hypertension. We’re now treating osteopenia. That’s the pre-osteoporosis.” Mishori said that “life is pre-death” and that doctors can choose to treat many things, but that they need to better evaluate which tests are really worth doing and which ones cause more harm than good.

You can read the full transcript here.

MS. SUSAN PAGEThanks for joining us. I'm Susan Page of USA Today sitting in for Diane Rehm. Diane is recovering from a voice treatment. Most of us get medical tests we don't need. That's a fact recognized by almost everyone in the healthcare field. Last week, some medical and consumer organizations issued guidelines about tests we probably should skip. Joining me to talk about the guidelines, Dr. Ranit Mishouri, a family physician and associate professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, and Shannon Brownlee of the New America Foundation.

MS. SUSAN PAGEJoining us by phone from Walla Walla, Washington is Dr. Christine Cassel of the American Board of Internal Medicine, and by phone from La Jolla, California, Dr. Eric Topol of Scripps Health. Well welcome to you all, and thank you for joining us on "The Diane Rehm Show."

DR. CHRISTINE CASSELGood morning.

MS. SHANNON BROWNLEEHappy to be here.

PAGEWe invite our listeners to join our conversation later in this hour. You can call our toll-free number, 1-800-433-8850, send us an email to drshow@wamu.org, or find us on Facebook or Twitter. Well, Dr. Christine Cassel, let me start with you. What's behind this effort to identify some medical tests that people are getting that perhaps they shouldn't be?

CASSELWhat's behind it? Well, first of all, thank you for inviting us for this conversation, and I very much appreciate the chance to discuss this in a broader group like this, precisely because what's behind this is the need for doctors and patients to have the conversation about what do they really need. There is a lot of waste in the healthcare system. There is ample research to support that. The question is, how do we find what's wasteful and how do we reduce it? These nine societies have taken a really important first step in identifying five things in each of their areas that potentially are sources of overuse.

CASSELNot all the time, not a hundred percent of the time, but where care really needs to be personalized to the individualized patient. Patients therefore need to have the same information that the doctors have, and that's the important partnership that we have with consumer reports in putting this information out.

PAGEAnd so what are some of the tests that you're talking about that could be optional or perhaps you don't need to have routinely?

CASSELSome of the tests that have been noted are things like CT scans or MRI scans of the head after an uncomplicated fainting spell without any other symptoms, an annual cardiac stress test for a person who has no sign of cardiac disease and no risk factors, or routine chest x-rays or EKGs as part of an annual physical or before outpatient surgery or minor surgery, and then a very common one is MRI of the spine within the first six weeks of the onset of lower back pain.

CASSELI would also mention that some of these things are treatments rather than tests because there are routine treatments like antibiotics for colds or for uncomplicated chronic sinus inflammation that can lead not only to excess costs for the patient, but also can lead to adverse effects from the medication itself.

PAGESo Shannon Brownlee, how big a problem do you think this is?

BROWNLEEIt's really quite a significant problem. There have been a number of estimates for how much of the care that's delivered in the United States is unnecessary care, and it ranges from 20 all the way up to 50 percent, and it's hard to get a handle on it, but given that various groups have come up with similar estimates, it looks like we're giving a lot of unnecessary care.

PAGEAnd so why does it -- I mean, a patient might say, you know, maybe I don't really need this test, but sometimes it catches something I didn't know I have, so why the problem with going ahead with some of the unnecessary tests?

BROWNLEEIt's a problem because all unnecessary care still poses risk, so even an unnecessary test, even though test might not necessarily be terribly risky, it can lead to further testing that's more invasive that can then lead to harm. It can lead the doctor down the wrong path. It can make the patient worry about things that aren't there. It can also lead to treatment that isn't necessary.

PAGEAnd so why do -- why are there so many tests being conducted that aren't necessary?

BROWNLEEThere are a lot of reasons. One of the reasons is fear of litigation, that physicians are legitimately afraid of being sued, but that's often put forward as being the main reason, but in fact it's only one of many. We pay in a way that rewards everybody, hospitals and physicians to do more rather than do what's right. Patients ask for things, all kinds of cockamamie things that they don't really need. There are sort of psychological reasons for it, where it's scary not to know for both patients and physicians, and so they tend to sort of over test. But over treatment, which is a little bit different, which is giving treatments that aren't necessary, also has many, many, many causes.

PAGEWell, Dr. Topol, you were laughing I think when you said that patients demand a lot of cockamamie things. What were you thinking?

DR. ERIC TOPOLWell, I think the issue is not really driven by the patients. In fact, most of these procedures and tests are very much driven by physicians, and so I applaud Christine Cassel and the ABIM foundation for getting their professional societies to put some things together here, but it's just scratching the surface. Not only are there, you know, just these nine professional societies, there's still I guess another eight that are gonna come through with their top five in the fall, but, you know, we ought to have 50 of these for each of these societies, but the problem has been that this is a physician-driven story and a lot of these are sacred cows with no evidence and, you know, this a long-awaited thing and mainly it's because the professional societies have been unwilling to take on their physician membership and so this has been a big problem.

PAGEDr. Topol, why do physicians drive unnecessary tests? What's their motivation?

TOPOLWell, you know, a lot of this is ritualistic, you know, getting a stress test in a patient who has had heart disease every year, or getting a pre-op, you know, stress test. These are things in the cardiology world where I live where, you know, these have just been done over the years without, you know, any evidence. And so it's been a problem, and actually one of the bigger issues is it doesn't get into enough details, so for example, a lot of the testing that's done in the cardiology sphere, and of course there are a couple of other societies that commented on this, is nuclear scans.

TOPOLAnd nuclear scans, you know, this is a big problem. A nuclear heart scan is equivalent to 2,000 chest x-rays, and, you know, I wrote about this in the "Creative Destruction of Medicine" book that just came out about how we are fixated on using these scans because in the cardiology community, they're highly remunerative, and something should be done to stop this, you know, massive overdose of radiation throughout our country.

PAGEWell, Dr. Ranit Mishori, you are a family physician yourself. What do you find when a patient comes in to see you? Do they want a lot of tests, or do you feel obliged to do some tests that you don't think are really necessary?

DR. RANIT MISHORISome do, some don't. The interesting thing is the day those recommendations came out I had five patients in the morning who, in succession, three had come in for sinusitis and wanted antibiotics. I ended up giving antibiotics to one. One came in with a generalized rash that she had probably because she was on antibiotics with something that she wasn't really -- that she didn't really need it for, and the fifth one came in having had -- a 41-year-old woman having had a mammogram that then was positive and she had just had a needle biopsy and had an infection.

DR. RANIT MISHORIIt was very -- I don't want to say that it was funny, but that's what happens every day. To me, these guidelines are really game changing. What happens is often I'll have a patient who has just come back from the gastroenterologist having had a colonoscopy that's completely normal, and then I say, oh, great, you need another one in ten years, and the patient will say no, the gastroenterologist told me every five years, and then who do you believe?

DR. RANIT MISHORIDo you believe me, the primary care physician, or do you believe the specialist? So that created a lot of sort of interprofessional tension here, and the fact that so many societies signed on is for me wonderful as a primary care physician.

PAGEWell, now why do you think the gastro -- whatever the specialist you just named...

MISHORIThat gastroenterologist.

PAGEWhy did that person say every five years when you were saying every ten years?

MISHORIWell, I don't know individually what people are thinking, but overall, there's evidence that this is a money-generating activity for gastroenterologists. So I think it took a lot of courage and wonderful insight and leadership on the part of their society to say, listen, really, you don't need to have that if you're, you know, a regular risk patient. You don't need to have that ten years, and I applaud them for saying that. And it's just not just gastroenterologists. I see it many other things, many other specialists, and I end up coming into conflict in the exam room with a patient who says, well, My OB/GYN said this, but you're saying that. Where does it take me?

PAGEYou know, I know that when new recommendations came about the frequency of having mammograms, there was some outcry about the idea that care was being rationed to save money, and I wonder, Shannon Brownlee, if you think these recommendations could be used by insurance companies to limit someone's availability to test, or to lead to ration care?

BROWNLEEOf course they could be, but the fact is, is that I think that the worry that this is all about rationing is hugely overblown and very politicized. This is really -- the culture in this country both on the side of patients, but also on the side of physicians, is more is better, and physicians and hospitals get rewarded for more -- delivering more. So most of the cultural impetus is towards delivering more, not towards delivering less, and this is -- I have to applaud the American Board of Internal Medicine for doing this, and the specialty societies because it really is an absolutely crucial first step towards what ultimately has to be a larger cultural shift, and that's gonna take more than lists of things you're not supposed to do. It's also gonna take a different way of thinking about healthcare and thinking about medicine.

PAGEShannon Brownlee, she's acting director of the Health Policy Program at the New America Foundation. We're gonna take a short break, and when we come back, we're gonna talk about the article that instigated this whole effort, and also take your calls and questions. You can call our toll-free number, 1-800-433-8850, send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Stay with us.

PAGEWelcome back. I'm Susan Page of USA Today sitting in for Diane Rehm. We're talking about the effort to limit unnecessary medical tests. And with me in the studio is Shannon Brownlee of the New America Foundation and Dr. Ranit Mishori, family physician and associate professor of family medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

PAGEAnd with us on the phone Dr. Christine Cassel, chief executive officer of the ABIM Foundation and Dr. Eric Topol who's a noted cardiologist, director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute in La Jolla, Calif. And he's also the chief academic officer for Scripps Health. He's also editor-in-chief of theheart.org.

PAGEWell, we were talking just before the break about how this whole effort got started. It was really an article, Dr. Cassel, that got this ball rolling. Tell us about it.

CASSELThis was an article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Howard Brody, a physician ethicist and colleague of mine who was writing about two-and-a-half years ago during the intense debate about the health care reform bill. And he was arguing that physicians really need to take leadership in the area of health care reform more broadly and particularly around reducing overuse and reducing waste in order to be able to accomplish two things.

CASSELOne is to reduce our rising costs of health care which are affecting everyone. And secondly, to make possible new innovative ways of paying for health care that are not based on the volume kind of payment that we talked about before the break, but based on better value for consumers. So Brody made this suggestion. He said, why doesn't every specialty come up with five things, just five things in their area that are susceptible to overuse and that need to be examined by the physician and the patient?

CASSELAnd then, subsequent to that, we funded a project by the National Physician Alliance which put out five things for three primary care areas. And that led to the idea, number one, of expanding to, as Dr. Topol said, to every other specialty that we possibly could, and also partnering with the consumer organizations because a big part of this is getting the message out to consumers.

CASSELThirty percent of physicians, just like Dr. Mishori said, respond when the patient comes in and asks for something. They don't have time under the current payment system to have a long conversation explaining why you don't need that, and so too often people will just respond to it. Susan, I wonder, though, if I might also say something about the insurance question that you asked earlier.

PAGESure, please go ahead.

CASSELThat I think it's really important for people to understand that these -- almost all of these 45 things that the societies have picked and the subsequent ones that will be coming in the fall are not things that you can say should never be used and therefore it really isn't possible for insurance companies to say, well we're just not going to pay for this. These are things that really need individualized decisions, clinical judgment and a discussion with the patient.

CASSELSo it really does depend on the professionalism of the physician involved and of the specialty in putting forward these ideas and the data behind them, but also on better educated consumers. So it's really about that empowerment of the patient.

PAGEBut I do wonder if it might limit the flexibility of a doctor to order one of these tests when he or she thinks it is necessary, if there's a guideline that says routinely it's not necessary. We've all had experiences with insurance companies who are resistant to anything that's going to cost the insurance company any money.

TOPOLThat -- yes, Susan, this is Eric. I agree with your point and that's my biggest concern here is not that we're finally seeing some guidelines but that the guidelines could be twisted away from the individualized approach. I think it's great that Christine has emphasized that but all too often we've seen in the past when insurance companies can use something to ratchet down their coverage that can occur. And it's so essential that we don't lose the individual story here.

TOPOLSo, for example, the gastroenterology group that said a colonoscopy every ten years. Well, you know, we have genomic markers that would make someone higher risk and is that going to be a reason why your colonoscopies wouldn't be performed, you know, at a more frequent time period? So these are just examples of new information that's coming on an individual basis that could reshape what would be the right thing for that person.

PAGEYes.

CASSELAnd, Eric, that's why each one of these says except when there is high risk or except under certain clinical conditions. And so I agree with you, we really need to make sure that is part of what the message is.

BROWNLEEAnd this is Shannon. This argues for a very different way of paying physicians. I mean, the whole idea that you pay the physician a separate fee for every single little thing that they do, every office visit, every procedure, every test, every colonoscopy is part of the problem. We ought to be paying physicians as groups to take care of groups of patients so that they can make decisions -- so that this is a decision that's between physician and patient, not with an insurance company inserting itself into every single little piece of it.

PAGEDr. Mishori.

MISHORIYeah, also it calls for a change in how we educate our future physicians, residents and medical students in not just saying, okay this is the condition that we're suspecting here. What test would you like? But specifically saying what test would really give you a clear idea of whether ordering it or not will change how you manage a situation.

MISHORIAnd, you know, young physicians, even more practiced physicians don't really know how much some tests cost. So educating us, educating our students, educating our residents about the cost of everything but also what some of these tests can and cannot give us is a huge step forward that we need to take.

PAGEWell, let's -- yes, let's take some of our callers and see what they have to say. Let's go first to A.J. He's calling us from Orlando. Hi, A.J., you're on "The Diane Rehm Show."

A.J.Thank you very much for taking my call. I wanted to comment. I am a paramedic here in the State of Florida and one of the things that I am specifically concerned about is that it's seeming like there's a call for the limiting of these routine tests. But the problem with that is is that a lot of times when I get to a patient, of course, you know, it's a 911 call. And the reason why I'm getting called to that patient is because their doctor didn't seem very concerned and didn't want to put them through quote unquote unnecessary routine tests.

A.J.And the biggest problem, not only did they not do the routine test, was that their doctor failed to employ the same practices and principles that we learn in paramedic school, which is my primary instrument is patient assessment. They do not take the time to sit down and talk with that patient, find out what's actually going on and asking the right questions. So I'm very concerned that, you know, if we have a whole bunch of medical professionals going, well let's look at limiting, you know, these routine tests that could very well be life saving.

PAGEAll right, A.J. Thanks so much for your call. Who on the panel would like to respond to that concern?

CASSELI would.

PAGEYes, Dr. Cassel, please go ahead.

CASSELEverybody would, I'm sure. Because I really appreciate A.J.'s perspective on this from the paramedic side, but -- and I completely support the idea that physicians need to have the ability and the time and the payment structure that allows them to actually spend the time doing what they spent 15 years in training learning to do, which is to assess the patient, not to just blindly order routine tests.

CASSELThat's exactly, I think, what's behind the professionalism driving these recommendations is that if you do a good history, if you know your patient, if you're confident the patient will come back to you and you'll follow up with them if symptoms develop, then these routine tests are even less useful.

PAGEDr. Topol, did you want to weigh in as well?

TOPOLYes, I would. Thanks, Susan. I think it's not a matter of life saving. This is about actually -- the whole idea here is the opportunity to do things, not just bending the cost curve but safer. So one of the things that I'm concerned about is I like this choosing wisely title that the ABM selected for this program, but I would like to say choosing more wisely. That is, you know, most of the recommendations or the biggest cluster is around imaging and it's -- and the massive use of ionized radiation. But no patients are being told how many (word?) that they're getting with their tests.

TOPOLSo as opposed to A.J.'s concern, mine is just very different and that is why aren't we telling each person when they have these scans, particularly the high radiation scans, nuclear and C-T, exactly how much radiation they're getting because accumulatively that's a significant risk of cancer for many individuals. And going back again to the cardiology example, every year doing a nuclear scan because it's highly remunerative and it's also engendering a very serious risk over time.

PAGEDr. Topol, do you think that the issue of profits for doctors is a significant driver in this?

TOPOLWell, I think -- we know the nuclear cardiology world has -- there's almost 10 million of these scans being done each year in the U.S. And that's why it was regretful to see in the ACC, the cardiology recommendations, they didn't single that out as a key concern so, yes, I do agree, Susan, that that is an issue.

PAGEThink how hard it is, though, for a patient who goes to see his or her doctor and they're recommending these tests, and maybe there's not a big cost concern because your insurance covers it and yet you're worried they're not really necessary. Dr. Cassel, what's a patient to do then?

CASSELWhat's a patient to do in the situation where they're not sure that the test is really necessary, I think ask the doctor. That's exactly what we're hoping to do, or even get a second opinion. I think in many situations we are encouraging patients to be more empowered and to have better information. And if they have any doubt I think that they have every right and every reason to seek another opinion about it.

CASSELThere is though, to Eric's point, significant risk that is often not conveyed as part of these routine recommendations. And those are questions that I would hope, in response to this campaign and to the outreach of all these societies to their members, that physicians would make more clear in their interaction with the patient. But if they don't the patient should ask, is there any risk to this test and what would be the downside if I don't do it?

PAGEDr. Mishori.

MISHORIYes, and I also -- something that Dr. Cassel said before is the importance of continuity of care. If you know your patient and the patient knows that they can trust you and you know them and you know when they're well and when they're sick, having that conversation makes it much easier over a length of time to figure out which tests are right for that person.

MISHORIAnd if you tell that person, listen I don't really think you need to have antibiotics and let's just wait another 48 hours, they're more likely to adhere to what you're recommending to them than if it's a brand new person and boom you're telling them, no sorry, I'm not going to give you that treatment or send -- order that diagnostic procedure. So, you know, having a relationship between the physician and the patient is immensely important in this context of what we need to order or not.

PAGEI'm Susan Page and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We're taking your calls, 1-800-433-8850. You know, that's certainly true. And if you have a doctor you've gone to for a long time and can trust you can have that kind of relationship. But, you know, at my company, the preferred provider network seems to -- you know, for the insurance company that covers you seems to change every year. It's very hard to maintain a relationship with a single doctor.

BROWNLEEAnd this is one of the fundamental problems that we have right now with the way that we pay and that we have this third party payment system that ultimately often breaks up these relationships. So that continuity care is absolutely essential but patients can still really change the kind of interaction with their physicians by asking questions.

BROWNLEEAnd there's a movement within medicine right now called shared decision making, which is really aimed at making sure that patients have the information they need in ways that they can understand so that they can understand what their treatment alternatives are. And it -- but it applies not just for when there are multiple alternatives, for example when you have an elective decision ahead of you. It also applies whenever a physician recommends a test or recommends a treatment. You say, what are the alternatives? What are the risks on each side of doing this or not doing this? And can you explain it to me in a way that I can really understand?

PAGEYou know, it does seem like that basic responsibility of the patient has been changing in recent years, that we expect patients to take a lot more responsibility for their own care. Have you seen changes in that, Dr. Topol?

TOPOLYes, I have but I think we have a long ways to go. I think that now that we're starting to see data, you know, going to individual smart phones and accessing even genomic data, interaction with drugs, and as I've been calling for, you know, getting the actual data of radiation exposure. You know, there's so much more for each individual to get, but the trend is clearly -- the access to laboratory tests, access to notes from the office, all these things are really vital going forward to give the -- what was previously called empowered but now actually, you know, could fulfill that real concept.

PAGEDr. Cassel, you mentioned the partnership with consumer reports. How is that working? How does that work? What is the partnership that you have?

CASSELWell, a couple of aspects. One is that consumer reports already have launched a major outreach to readers and to consumers even more broadly beyond the subscribers to their magazine to put out evidence-based trusted and understandable information to consumers.

CASSELSo we want consumers and patients to be empowered and to be partners in decision making, as Shannon mentioned. But we don't expect every patient will have gone to medical school and really understand everything about the science and the language that we use. And that is a big part of what's so valuable about our partnership with the consumer groups, that they know how to translate this information into meaningful language to make it understandable to the public more broadly. And then also have very broad dissemination channels.

CASSELIn addition to consumer reports, they have -- consumer reports themselves have reached out and helped develop a network of 11 different large consumer organizations ranging from AARP to Wikipedia communities so that there will be lots of ways that this information will be available and available in understandable forms.

PAGEOkay. Shannon Brownlee.

BROWNLEEYou know, there's a danger here, though, that we can't lay this at the feet of patients. It's not just...

CASSELRight, right.

BROWNLEE...the patient's responsibility, and I don't think that Dr. Cassel was saying that in any way. But this really has to begin with physicians and it turns out that there are a lot of doctors that are eager to start making the kind of shift. So I'm co-organizing a meeting with a doctor of the (word?) in Boston. And Dr. Cassel will be there, Howard Brody, the author of that original article will be a panelist as well. And the meeting is called Avoiding Avoidable Care. And this group of physicians is just jumping at the bit to start talking about how we shift our emphasis towards the right kind of care for the right patient.

PAGEWe're going to take another very short break and when we come back, we'll continue our conversation about necessary and unnecessary medical testing. Stay with us.

PAGEWe got an email from Matt in Texas. And here's what he writes. "I am a fairly healthy 39-year-old male in Plano, Texas. I went to see my primary care physician and found out that my cholesterol was borderline high. I was encouraged to see a cardiologist due to my age and slightly high cholesterol numbers. So I went and had a $220 office visit, a $210 echo-cardiogram and a $1,800 stress test. This equates to having your headline go out in your car and having a mechanic replace your entire electronic system. This is what is wrong on the provider's side of fee for a service health care. All of these tests, $2,230 worth because my numbers were borderline." Is this what should've happened in this case?

MISHORII think, both Shannon and I's jaws have dropped here. This is completely uncalled for, in my opinion. But we see it all the time. The question is, you know, we see it in people coming every year for their annual physical and getting a bunch of tests and EKG's. And we see it in doctors requesting pre-op testing that are unnecessary. You know, and also the whole idea of having borderline something. So now, we're treating pre-diabetes, we're now treating pre-hypertension. We're now treating osteopenia. That's the pre-osteoporosis.

MISHORISo, you know, life is pre-death. So you can, you know, you can treat everything but, you know, it's not about cost saving here, it's about causing harm. And a lot of these tests can find things that are clinically completely irrelevant. So, you know, we keep talking about the costs and the costs but it's really about preventing harm from patients. And, you know, some of us do more than is necessary. And I’m definitely guilty of sometimes ordering stuff that's really not to hardly necessary. But, you know, this is not the first time I hear of a $3,000 annual physical. And it shouldn’t happen.

CASSELBut Susan...

PAGEYes.

CASSEL...Susan, let me also weigh in here because I think, to Matt's point. You know, high cholesterol and Eric probably has a strong opinion about this. High cholesterol really is an important risk factor in heart disease and especially in a young man his age. And so, you know, the first thing you want to do, if it's borderline, is repeat the test. But the second thing to do is talk to the patient about lifestyle changes they can make that can reduce that cholesterol before you even begin talking about other tests or medications. And it sounds like -- I don't know if that happened but it's important for us not to have your listeners think we should ignore potential abnormalities that occur in these tests. But the response isn't necessarily to order a whole bunch more tests.

PAGEWell, Dr. Topol, do you think this was an appropriate response given Matt's age?

TOPOLNo, I don't, but, you know, welcome to American medicine. I mean, that's really -- he could've even wound up having a cardiac catheterization because of a false-positive exercise test. That's the kind of thing that happens on a daily basis. So, no, I mean, an isolated, slightly increased cholesterol, I completely agree with Christine, that that could be addressed, you know, through lifestyle. And the other thing, of course, is we overdose of medications, the statins, which we now recognize have a significant risk of diabetes in the tradeoff for someone like this, a young person taking statins for the rest of your life.

TOPOLNot only is the expense an issue, but also the risk. So, you know, I think that this is unfortunately is representative of using too many tests, of not really focusing in on the individual, here a young man with isolated increased cholesterol. And look what happens with all the tests that are ordered and really is a -- that's, you know, why this whole program, I think, was long overdue and it's great to see that it's starting to happen.

PAGEWell, Matt, thanks very much for sending us that email and we're glad that things turned out to be all right. Let's talk to Tina. She's calling us from here in Washington, D.C. Tina, you're on the air.

TINAThank you. There is a foot side to the conversation about unnecessary tests and screenings. And that is a climate that perhaps is reducing the opportunity to deploy new screenings and tests. Medical science is improving every day. For example, with lung cancer screening, the National Cancer's Institute has concluded that low dose screening with radiation about the level of a chest x-ray could improve lung cancer mortality by at least 20 percent. And it's not just sort of drive in and get a chest scan.

TINABut if there's a continuum of care that goes with that. And one of the challenges is in the climate of unnecessary medical screening. There seems to be a resistance to deploying this technology that we know works and we think the consumers ought to have access to that information. So just curious how the climate of this conversation you're having could interfere with access to new life saving tests.

PAGEOkay, Tina, thanks so much for your call. Shannon Brownlee.

BROWNLEEWell, let's talk specifically about the CT screening for lung cancer. The latest clinical trial suggests that, yes, there may be a benefit, but it's for a very select population of patients. And so if what we're talking about is saying, gosh, everybody ought to run out and get a lung cancer screening test, that's not a good use of that test.

BROWNLEEIt is only really going to be beneficial if, to anybody, it's going to be beneficial to the people who are at the very highest risk of lung cancer. So I agree that there is always the possibility that we're going to restrict people's access to things. But Americans have an idea that if it's new, it must be better than what's old. If it's shiny and highly technological, it must be better than what's low tech. And that isn't always the case.

PAGEWe've gotten a lot of emails like this one from Carol. "Aren't at least some of these tests ordered to avoid malpractice?" Dr. Mishori, do you sometimes feel you're ordering unnecessary tests for that particular reason?

MISHORIWell, it's always scary because there's always the doubt that something might be cancer or life threatening and you don't want to get that phone call, you know, doctor, you didn't order that test and now I have advanced cancer. There's always an option that that's going to happen. But you try to rationalize your decisions and look at the evidence, look at what the patient is telling you, look at their symptoms, look at their physical examination. Yes, there's often a lot of uncertainty in medicine and that's certainly a point that drives some of this testing. But if you think rationally and you can talk it out with your colleagues, hopefully, most of the time, you won't have to face these cases.

PAGEDr. Topol, do you think that's a -- you talked about the profit motive as being one factor driving doctors to do unnecessary tests. To what degree do you think fear of malpractice suits is also a factor?

TOPOLWell, as mentioned, I think Shannon brought up earlier, it's out there, but I think it's a very minimal issue. That if things are well documented in the medical records about why a test wasn't ordered, that should preempt, you know, that the fact that something was thought about and why it wasn't done should preempt any concerns about a medical, legal consequence. So, no, I think that the main reason goes back to the techno-centric, ritualistic and ruminative aspects that we talked about earlier.

PAGETo what degree does the Affordable Care Act that's widely known as Obama Care, to what degree does it try to address this issue, Shannon?

BROWNLEEThe Affordable Care Act is mostly about coverage. But there's a significant part of it that really is aimed at this very problem of unnecessary care, of misuse of care and of not giving people care that they actually do need. And so there are several provisions in there that are aimed at addressing this. One of them is the accountable care organizations, which is this idea that you pay groups of physicians or a hospital and a group of physicians to care for a population of patients. You don't pay them a fee for service in the same way. Now, is this going to be the panacea, no? Is it going to work the way intended, not necessarily? But the act really does recognize that this is a huge, huge problem in American medicine.

PAGEDo you think, Dr. Cassel, that the Affordable Care Act will make a difference on this?

CASSELI think Shannon is right, that the largest and most important impact of the Affordable Care Act is to expand coverage because there aren't many people, I'm thinking about Matt's email, there aren't many people who have the capability to put out $2,000 or $3,000 out of pocket for their own medical care and particularly if it turns out that this is not meaningful or necessary for them. And yet, more and more Americans are either completely uninsured or are buying these high deductible insurance plans where they have to pay the first $2,000, $3,000, even $5,000 out of their own pocket.

CASSELSo that's the most important aspect from my perspective of the Affordable Care Act as well as the innovations, as Shannon mentioned, in how we organize care in groups better to deliver seamless and better coordinated care, so that a patient doesn't lose touch with their doctor or fall between the cracks when they get sick and they don't know who to call at night or on the weekend. So that kind of change in how we provide service is really important.

CASSELBut there also, Susan, is another aspect of getting this right information to the public as well as to the medical community and that's the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute or PCORI, that is a very important federal entity that will support the research that's needed to really get the best information and the most credible form out there to the medical community and the health care community and also available at the same time, to the public so that the consumer organizations can make use of it.

PAGELet's go to Indianapolis, Ind. and talk to Jennifer. Jennifer, hi, you're on the air.

JENNIFERHi, thanks for taking my call.

PAGEYes. Please, go ahead.

JENNIFERI just was floored at how my philosophy changed when I had a co-pay. I would go with the doctor's recommendation for the care of my four children. However, when we were forced into a high deductible insurance, I became a lot more concerned about the expense of tests that doctors recommended for my children. A case in point, very quickly, my daughter had a vague, non-life threatening pain that needed addressed and we were having lab tests and referrals to specialists and then it finally came to an abdominal x-ray that I was unwilling to pay for.

JENNIFERAnd I said if she just needs to go to the bathroom, isn't there a better way to handle this? And found a better way through research on myself. I never thought for a minute that I'd ever take the side of the insurance company but I can see how quickly, when things were out of pocket, I became a lot more diligent in looking for alternatives. And I'm often frustrated, the pressure that I have to be part-time doctor and part-time mediator between the doctors and the health care industry.

PAGEWell, that's interesting because we're talking about the need for patients to take this responsibilities but it takes a lot of guts to question what a doctor is saying one of your kids needs.

JENNIFERExactly because their care is the most important thing and between hours of research on the internet, asking other mothers and looking for any alternative to save me money but also to put her health first, I find it a little ridiculous that I have to put forth that much effort just to take care of my daughter.

PAGEYeah and it...

JENNIFERI have insurance and pediatrician.

PAGE...yeah. Well, Jennifer, thanks for your call. I hope your daughter's doing well.

JENNIFERShe is. We went to a chiropractor and actually things got corrected very inexpensively.

PAGEAll right, Jennifer, thanks very much for your call. I'm Susan Page and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." So to Jennifer's point, do you think patients generally understand what these tests costs?

BROWNLEEI don't think they have any idea how much tests cost and until suddenly they...

CASSELUntil they have to pay for it.

BROWNLEE...they have to pay for them, themselves. But, you know, here's the really crazy part, the same test can cost something completely different depending on who you go to and which hospital you go to and who's paying. I mean, you know, we have this completely crazy system where when you talk about costs and price, it's not very transparent at all to anybody, the doctor, the patient, it's only transparent to the insurer.

PAGEAnd is there an effort to make it more transparent, Dr. Cassel?

CASSELThere is and actually that is also part of the Affordable Care Act, that I think, people will begin to see in the next couple of years, that more of that information being made available. But I completely agree with Shannon, that it is virtually impossible to get consistent information available before something is ordered especially if your insurance company is paying for it. And the experience that we heard from Jennifer is unfortunately the sticker shock that happens when a patient who doesn't have insurance or has high deductible insurance, finds out exactly what the hospital or the physician office is charging for this.

PAGEHere's an email from Jan, we've gotten a couple others that are like it. She writes, "Often doctors have a financial interest in the machines. This happened to me some years ago. My doctor ordered three MRIs at once. I investigated who owned the machine, my doctor did with several other doctors." Dr. Topol, does this happen a lot?

TOPOLUnfortunately, it does, although over the recent years, there's been more clam down and awareness of this issue. But it's still out there as a significant problem. But I would like to respond to this -- well, you know, the Affordable Care Act would take too long to achieve the transparency that we need and that the consumer and patients need. And that's why I really have been calling for a consumer driven health care revolution. And that is, to demand this data that -- their entitlement.

TOPOLWhether it's not just a cost, we talked about radiation. But it's also about having all the information, you know, what's in the chart, what's in the lab tests, you know, what's in their genomic's, which, of course, the AMA is fighting the government against people having their direct access to their genomic data. All of these things represent a shift away from -- that we need from the priesthood and the doctor-knows-best attitude. And this is just something that has to be grappled with and, you know, the choosing wisely campaign is just one part of this but we need a lot more.

PAGEDr. Mishori, so to sum up at the end of this hour, for patients who've come to you, what would you tell them they ought to be doing themselves? Or what they can do to make sure they're getting the tests they needed but not tests that they should not be getting?

MISHORII think the most important part is to ask questions. And I'm not offended is somebody says, do I really need this test, and tell me why I need it, explain to me what the outcomes might be, the good outcomes as well as the bad outcomes, and what am I -- what are some side effects from this treatment or from this diagnostic test? I would love for every patient to be able to ask me these questions if, for some reason, I'm in a hurry and I don't have time to explain it, please stop me and ask me these questions.

PAGEDr. Ranit Mishori, Shannon Brownlee, Dr. Christine Cassel and Dr. Eric Topol, thank you all for being with us this hour on the Diane Rehm Show.

CASSELYou're very welcome.

TOPOLThank you, Susan.

PAGEI'm Susan...

MISHORIThank you.

PAGE...Page of USA Today, sitting in for Diane Rehm. Thanks for listening.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.