Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

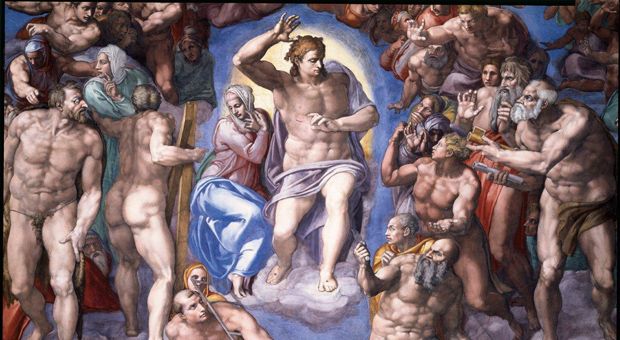

The central portion of "The Last Judgment" by Michelangelo.

Michelangelo created some of the most celebrated works in the history of Western art, including the “Pieta,” “David” and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Born in Italy during the Renaissance, Michelangelo was considered a genius in his own time. He was also known to be egotistical, hot-tempered and consumed by his work. He fought the notion that the artist was simply a craftsman and often clashed with patrons over creative control. Michelangelo insisted that he need answer only to his own muse. In doing so, a new book claims, he revolutionized the practice of art – and the role of the artist in society. A discussion about the life and legacy of Michelangelo.

MICHELANGELO: A Life in Six Masterpieces by Miles J. Unger. Copyright © 2014 by Miles Unger. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. Today, we take it as fact that an artist expresses something of himself in his work, but that idea did not always exist. Art historian Miles Unger argues this was largely the invention of Michelangelo. In his new book titled, "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces," Unger traces the life and work of one of the titans of the Renaissance.

MS. DIANE REHMHe calls him the first modern artist who paved the way for a contemporary understanding of the role of the artist in society. Miles Unger joins me in the studio and throughout the hour, I'll look forward to hearing from you. Join us by phone at 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. And welcome to you, Miles Unger.

MR. MILES J. UNGERIt's a pleasure to be here, Diane.

REHMSo good to see you. I'm interested in the fact that you took Michelangelo's life in six masterpieces. Why did you decide to do it that way?

UNGERWell, it's one of the frustrations I have when reading biographies of men and women who are known primarily for their achievements in the life of the mind, that you tend to have two kinds of books. You have books that are sort of narratives of their lives, that tell the stories of their lives, but they give short shrift, generally speaking, to the works themselves, partly because, if you're writing a narrative biography, to dwell at length on the works tends to slow it down.

UNGERIt interrupts the flow. So that kind of biography tends to be wonderful on the anecdotes surrounding the artist or the writer, the composer, but less good at analyzing the work itself. And then, there are the other kinds of books of course where they focus primarily on the work, but then give short shrift to the life and because the two are integrated...

REHMAbsolutely.

UNGER...it seemed to me this was a good way to do it, a kind of way to find, to strike the right balance between the life and the work, each of which informs the other and is hard to understand without the context of the other.

REHMSo the six masterpieces you chose...

UNGERYeah, there are other ways I think I could've done it, but this seemed like a fairly good collection. I begin with "Pieta," which he did as a young man, go on to the "David," to the Sistine ceiling with the famous "Creation of Adam," then we go back to Florence with the Medici Tombs back to Rome with "The Last Judgment" and finally, the great work that took up the last decades of this life, his work on the Basilica of St. Peters.

REHMBut that had to, in and of itself, be tough to do, that is to select those six masterpieces.

UNGERIt was. Well, actually, the book was originally titled "Michelangelo: A Life in Five Masterpieces," so I did have some difficulty. And the one work that I added on later was the Basilica of St. Peters, which is one of the great monuments of Western history, but Michelangelo's contribution is difficult to tease out.

UNGERIt's profound, but it's a story that's somewhat harder to tell. But I realized if I left that out, I would be leaving out one of the great dimensions of his achievement as an artist and that his work as a architect and also because since he spent the last 20 years of his life doing this, I thought the life would sort of end early and I wouldn't have -- I wanted to be able to continue telling the story of his life to then end and this was a way to do it.

REHMOf course, we all think of Michelangelo as a genius. Do you think of him as a genius and why?

UNGERWell, I know the concept of genius has come under attack lately. Malcolm Gladwell, for one, is not a big fan and says, you know, it's all birth, you know, when you were born and hard work. I think he was a genius. I think the term may be overused but there are few people for whom it fits as well as for Michelangelo.

UNGERAnd I think, in a way, he almost invented the notion of genius because there were certainly famous artists before him, great artists before him, but he was the one who really created that notion that art was not only the product of supreme skill, but was an expression of one's individuality, of his individual personality and that notion of a kind of tormented artist who sort of struggles.

UNGERAnd those struggles come out as part of the art, I think, was something that, really, Michelangelo contributes to our cultural consciousness. And one of the reasons I call him the first modern artist because that's the way we think an artist as somebody who's primarily interested in self expression, that it's not just -- and it's sort of a wonderful monument but that his or her character and personality and vision flows through the work of art.

REHMSo what you're saying is for the most part, those who came before were simply viewed as craftspeople?

UNGERYes. It was beginning to change. The prestige of the artist by the time that Michelangelo began his career was already rising. So it was not fair to say they were simply regarded as, you know, carpenters at that time, but the notion that an artist was the equivalent of a writer or a philosopher or even a prince of the church -- and Michelangelo's battles with the greatest, you know, popes and with cardinals, showed the extent to which he transformed the relationship between the patron and the artist and that, you know, who was responsible for the creativity of the work of art.

UNGERBut he, through his live, through his pride and his difficulty, he really emancipated the artist from the patron and said, I am the one who is the creative one. It is my work. And that's why he was so difficult to work with. You know, he had a very difficult time with collaborators. He didn't want anybody around him who was his equal so he wanted complete control over the work.

UNGERHe wanted it to be an expression of his vision.

REHMAnd how, give me an example of how a patron might have reacted to that kind of statement of control.

UNGEROh, they often -- depending on the patron, some were very sympathetic, some knew how to handle him, but Pope Leo famously said, you know, I'd like to commission a work from him, but he's terrible. I can't deal with him. And there's a famous case where when he was working on St. Peters near the end of his life that a cardinal, who later became a pope so a very powerful man, who at the time was in charge of the finances of this great building project, complained that Michelangelo was telling him nothing about what he was doing.

UNGERHe said, I'm paying the bills, you know. You know, I need to know, you know, what you're doing. And Michelangelo said, well, it's your job to pay the bills. I have no obligation to tell you what you're doing -- what I'm doing. It's my project, you know. You're just a bean counter, basically.

REHMWow.

UNGERYeah.

REHMAnd yet, the patron continued?

UNGERHe did. Well, in this case, this was Cardinal Cervini. He was still only a cardinal and the pope was backing him so he had -- when Cardinal Cervini became Pope Marcellus, things were a little more difficult, but fortunately for Michelangelo, he had a very short reign and was replaced by another sympathetic pope.

REHMCan you describe perhaps from your investigation what purpose Michelangelo saw in art?

UNGERI think he was really -- this is partly psychological. I think it goes back to his childhood. He was born poor, but he believed with some justification, though it was largely family lore, that his family was very aristocratic, that they were descended from the Counts of Canossa, which would be the sort of leading family of Tuscany for hundreds of years.

REHMHe thought that or...

UNGERIt was family lore and the Counts of Canossa, the current Counts of Canossa accepted this. Now, genealogies were a bit suspect and it was always -- families often found ancestors who were more famous than they actually had, but in this case, it was certainly family lore and there's some, perhaps, tenuous connection. So but there was a gap between Michelangelo's -- the reality of his life as a child, where his father was a sort of feckless person who proudly claimed, you know, I don't do any work because I'm an aristocrat.

UNGERBut then, he didn't have any money so they were living poor and he suffered the humiliations of this. But his sense of himself was as something greater. He had -- and when he became an artist, art was considered, at that time, a lowly profession for an aristocrat, but he had this compulsion to be an artist. But he wanted to be an artist in a new way.

UNGERHe wanted to be an artist who was the equal of the great philosophers, the theologians and the people who, in that era, were considered the true intellectuals of the day. And so I think what Michelangelo wanted to do was to lift art up to that level of a kind of philosophy, a moral philosophy and this, again, I think goes back to that gap between the reality of his life and his ambition, his pride in who he was.

REHMHow soon did he or others discover that he had a talent for art?

UNGERVery young. He was very precocious, As many sort of great geniuses are. His father wanted to send him, when he was 14, to a school of grammar, which was the way that a Florentine of the middle class would get a real job, a respectable job, maybe even enter politics. But Michelangelo had very little interest in it and he was always embarrassed by the fact that he didn't speak Latin 'cause he basically cut classes so he could study art.

UNGERSo he knew, himself, that he had this passion. I mean, like many artists, he was compelled to be an artist and so it came very early and other people recognized it very early as well.

REHMMiles Unger, he's an art historian and journalist. His new book is titled "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces. Do join us, 800-433-8850. Short break, right back.

REHMAnd welcome back. If you just joined us, we're talking about a new book. It's titled, "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces." Miles Unger is the author. He's an art historian and journalist. And here is an -- a tweet, "My favorite Michelangelo piece is one of 'The Bound Slave' displayed at the Accademia, such emotion displayed."

UNGERYes, those are wonderful pieces. In fact, when I go to the Accademia, I think I usually spend more time with the captives or slaves, as they're sometimes called, than the David.

REHMReally?

UNGERThere is something, I think, particularly to the modern sensibility about those works emerging from the stone but not yet completely released that is so powerful, particularly since the theme of these works is struggle. You know, the idea of the body or the soul confined within the body, which is a theme often in his work. And, yes, they are wonderfully powerful even in their unfinished form, perhaps even more because they're unfinished. And you can really see the sculptor at work on the stone as well, which is wonderful.

REHMIt's interesting. I want to go back to his early life, because, you know, five children and in this kind of shabby, gentility, living on a farm, father not working because he considered himself nobility. Did they -- how did they live? How did they exist?

UNGERWell, they could scrape by. I mean, his father, Ludovico, is constantly complaining about things like he had to cook his own meal. But being poor in those days meant usually have one servant, you know, and you are sort of, you know, your clothes were shabby. But they never lack for things to eat. And his uncle was a small-time banker and never very successful.

UNGERAnd it's kind of an irony that the one successful member of the family, the one who ended up supporting them all and raising the Buonarroti family back into that aristocracy that they thought they always belong to was the artist, the one whom his family his father beat because he said this is no profession for a true gentleman. So it's interesting that the artist turned out to be the one competent businessman in the family.

REHMHow did Michelangelo, after he had broken away from the kind of schooling his father anticipated for him, how did he begin to do his own art?

UNGERIt's an interesting story, partly because Michelangelo himself tried to cover it up a bit. He was always shaping his own legend. And while he was supposed to be in the classes learning how to read and write and polish his Latin, he started sneaking off through a friend of his who introduced him to the studios of the famous artists, the Ghirlandaio brothers. And he apprenticed for a couple of years as a studio assistant in Ghirlandaio's studio.

UNGERAnd -- but this is something that Michelangelo covered up because it seemed too pedestrian, an origin story for a man as great as he. He wanted to sort of act like he invented himself.

REHMCreated.

UNGERHe had no training, he was just sort of, you know, arose like Athena from the head of Zeus, a genius fully formed. But the truth is a little more prosaic than that. He did study for two years in Ghirlandaio's studio, where he learned how to draw and paint, which served him very well. Of course, he went on to paint the Sistine ceiling. His sculptural training, which he considered his first art is a little more mysterious.

UNGERHe did spend a couple of years in the sculpture garden of Lorenzo de Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent, who took him under his wing, saw his talent, took him under his wing. But it's not very clear what kind of real instruction he got there. And so, his -- how he learned to be perhaps the greatest stone carver of all time is a little mysterious. He -- one of the advantages he had was the Buonarroti farm in Settignano was a hotbed of stone carving.

UNGERA lot of sculptors came out of there. His -- the people he hung out with as a kid were often stonecutters themselves. So he probably learned on his own as a child.

REHMI see.

UNGERBut really didn't -- we don't really know what his formal schooling, if any, was in that area.

REHMTalk about how Michelangelo actually made his way to Rome. It was, as you said, deceitful. But it was his big break.

UNGERYeah. He had gone through, after 1494, when its first great patron -- 1492 when his first great patron Lorenzo de Medici died. He was sort of at loose ends for a number of years. Savonarola, the great fire and brimstone preacher had taken over Florence and ruled on everything from religious morals to artistic taste. It was not a good period to be an artist in Florence. So he tried to find a way to realize his ambitions.

UNGERAnd it was suggested to him that he carve a sculpture of a cupid and make it look like an antique. Now in the renaissance, antiques were much more highly valued than works by contemporary artists. And they said, well, you can fetch a good price for this in Rome if you -- so he was quite a skilled forger. He had learned, actually, to forge paintings and drawings to make them look like old master works while he was in Ghirlandaio's studio. So he carves this cupid in the manner of the ancients. He buries it in the ground for a few weeks. You know...

REHMHe buries it in the ground?

UNGERRight. And makes it, scrapes it, bangs it that makes it look old.

REHMRight.

UNGERSends it off to Rome where it gets -- it finds its way to one of the great collectors in Rome, Cardinal Riario, who first buys it for 400 ducats I believe. Very good price because he thought it was antique but has quickly discovered that it was a fake. And so he sends his agent back to Florence, angry, saying, you know, feeling he was duped. But then he realizes, you know, anybody who can pull this off must be somebody who has got some real talent.

UNGERSo he invites him to Rome and commissions him to do another sculpture, also in the antique manner but clearly not a forgery but a modern work. So this is really what puts him of the stage in Rome. And Rome was the place to be if you were going to be -- if you're a young, ambitious artist. There was the most money, the most commissions, most prestige. So that's how his Roman career -- and that sort of launches him on his career to fame and fortune.

REHMYou have a caller of the six works of art that you have focused on. Tell us about the Pieta of which, I gather, it takes him from 1498 to '99 to produce. You know, it takes your breath away even as you look at a colored print. And I remember looking at it in the flesh, if you will.

UNGERIn some ways it's easier to appreciate it in a reproduction, in fact, because now after the -- I remember it was attacked some 20, 30 years ago and now it's behind bulletproof glass. You can't -- it's very hard to see. So, in some ways, a good photograph works better, not that I'm discouraging you to go to Rome...

REHMYes, exactly.

UNGER...and see it in person. It has its own effect.

REHMExactly.

UNGERBut not only is it -- this work, it does take your breath away, but it was meant to. I think it was a bit of a showoff-y piece. He was a young artist who had still not established his name.

REHMHow old would he have been?

UNGERTwenty-three.

REHMTwenty-three when he did this.

UNGERYeah. So...

REHMWow.

UNGERAnd he had yet to really make his reputation. So he put in everything. I mean, he really pulled out all the stops, the carving is never more exquisite, more detailed, more finely polished. And it was the only work that he signed, interestingly enough. There's a whole story about his signature. It's across the strap that runs across Mary's breasts. He signed it. Michelangelo was making in very shallow letters.

UNGERAnd there's a story that's told about that because people felt this was kind of arrogant, you know, you don't sign your name right on the virgin's chest. But -- and the story tells the story that it was done because some people were in the cathedral and looking at it saying, oh, that was a work by one Gobbo from Milan. And Michelangelo was so mad about that, one night he goes into St. Peter's and craves his name.

REHMWow.

UNGERThat's actually not the true story. The true story is he meant it there -- he meant to put it there from the beginning. The strap only serves to carry his signature.

REHMI see.

UNGERAnd Vasari was basically covering him for what seemed like a very arrogant, boastful thing. But I think in this time in his career, he really wanted people to know, he really wanted to make his name with the sculpture. And he sort of this idea of kind of personal ownership was different from the way the Pieta was traditionally treated, which was as a kind of sacred magical icon. He really wanted it known that I made this. This is my work. Any magic that this work has is a attributable to me, and therefore he signs it in a very bold, almost arrogant way.

REHMIt is so glorious as one examined it in this close-up way. I mean, the Virgin with the Christ in her arms after he's been taken from the cross. And the folds of her dress, his hands, his feet, and the sadness on her face. I mean, it's extraordinary.

UNGERIt is.

REHMIt's all one can say about it.

UNGERIt is extraordinary. And, again, I think it was -- not all of Michelangelo's pieces are, you know, showoff -- it's -- I think I say in the book, it's like a -- one of those Paganini Cadenzas. It's meant to show off the skill of the, you know, just so elaborate...

REHMIt's okay.

UNGERAnd so. Yes, it is.

REHMIt's okay.

UNGERIt is. It's wonderful and...

REHMIt sure is.

UNGERAnd it helps the story. But this one particular part that I love, I think it sort of says everything about his skill. And the way that his skill is used to tell an emotional story, and that's the part where Mary's hand is right under his arm. And if you look at the way the flesh, the muscle of his arm just rises...

REHMRight.

UNGERThat mobility to sort of translate the human form into this. You can feel the weight of the body there. And I think that no artist before perhaps since has been able to sort of -- has that understanding of the body and the way bodies move and interact with each other as Michelangelo.

REHMMiles Unger, he's an art historian and journalist. His new book is titled., "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces." And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We've got lots of callers who'd like to join the conversation, 800-433-8850. Send us your email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. Let's see, to John in Danielson, CT. You're on the air.

JOHNWell, hello, Diane. It's always great to listen to you.

REHMThank you.

JOHNAnd your guest. I would like to ask the historian if his comments on the relationship between Bramante, Michelangelo, and Pope Julius II where Julius changes his mind from building, you know, the Michelangelo's design of a mausoleum to building the St. Peter's. So the (word?) mausoleum is up in San Pietro in Vincoli with Moses in the horns. And then, you know, Michelangelo is fleeing to Florence when he finds out. What does he think of that all whole relationship?

UNGERMichelangelo had a very stormy relationship with Pope Julius. I think they were very similar personalities. They were both incredibly ambitious, incredibly egotistical. But also incredibly invested in the work, I think. And somebody commented that -- I think the Venetian ambassador said that Pope Julius is a difficult man to deal with because what he says when he goes to bed in the morning is not what he says when he wakes up.

UNGERSo in the case of Michelangelo and the tomb, what happens is Julius invites Michelangelo to come to Rome to sculpt his tomb, which is going to be the greatest monument since ancient times dedicated to one man. But then, ironically, partly because there was no place to put such a grand structure in the old St. Peter's, his architect Bramante proposes to build a big, new edifice that will dwarf the old one.

UNGERIt'll be big enough to contain Michelangelo's tomb. The irony is it invest -- Julius invests so much time and effort in this project that he has no longer has any time for Michelangelo's work. Michelangelo is terribly offended. One day, he rushes after he's been kept out of Julius' chambers by a groom, Michelangelo returns to his house in a huff. He said, sell all my furniture, I'm leaving.

UNGERAnd he rides off to Florence. A few hours later, the pope's soldiers chased after him. So they're chasing him across the Roman countryside. And they finally catch up with him and, in Florentine territory, fortunately for Michelangelo, but the pope's troops can no longer arrest him. And he says, you know, if the pope wants me, he can find me in Florence. You know, I refuse to be treated like this. And the -- Michelangelo himself calls this the tragedy of the tomb, which lasts for 30 years of his life.

REHMWow.

UNGEROn and off and causes no end of difficulties.

REHMHe was a strong personality.

UNGERHe was. He was very temperamental, Mercurial and touchy. He was very sensitive. He's very -- a lot of pride, but it was a fragile pride and can be easily wounded.

REHMDid he ever marry?

UNGERNo, he never married. He once said that art was my life -- my wife. But he's probably also what we -- if he had lived today, he probably would have called himself gay. He really didn't have any interest in women romantically or sexually, though in the Renaissance they thought of these things differently.

REHMOf course.

UNGERIt was not -- his relations with women tended to be either very distant or nonexistent.

REHMMiles Unger. And the book we're talking about, "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces." Short break here. When we come back, your emails, your phone calls. I look forward to speaking with you.

REHMAnd we'll go right back to the phones to David in Wenatchee, Washington. Hi, you're on the air.

DAVIDOh, I love you so much.

REHMThank you.

DAVIDI just want you to know and so much I thank you for taking my call. It's gonna seem kind of trivial. One of the things that always drove me crazy as a hardwood floor and then as a contractor later is just when a material fails and there was a whole lot of that in Michelangelo's life where it was like he would've started -- I mean, we know the great sculptures that he made, but there were the other ones that if he had a truck, he probably would've run it over, you know, for breaking on me right there.

DAVIDI mean, the marble and everything he worked with.

REHMWhat do you think?

UNGERWell, there are a couple of very famous cases, the "Statue of the Risen Christ," was done in two versions because he was working on it, had almost completed it, then he found a vein of dark marble running through the face, which totally marred it and he had to completely redo it.

REHMWow.

UNGERBut one of the things about Michelangelo was he was a perfectionist and unlike most artists who would buy their material, their marble, from dealers, he actually spent years of his life in the quarries cutting out the stones himself. And he knew the way the stonecutters themselves did or perhaps even better, the quality of the material before it was dug out of the mountain.

UNGERSo he was very conscious of the quality of material and had probably much better success than most, you know. Rock is an unpredict -- is a natural material. It's unpredictable so it's not completely -- so he did have his failures, but for the most part, he knew his craft well enough to get the best material.

REHMMiles, we have to talk about the statue of "David." And I'm looking at a gorgeous color reproduction. Tell me what the reaction was when "David" was first unveiled.

UNGER"David" was commissioned by the government of Florence. It was in a particularly critical time. And it was facing foreign armies, facing invasion, the government was largely discredited after the execution of Savonarola so it was a very troubled time and they wanted a monument that would reanimate the people, that would bring them renewed faith in their own government and their own nation.

UNGERAnd they requested -- Michelangelo won the commission for this and -- it was originally meant to go on top of the Duomo, the Cathedral of Florence, where Brunelleschi’s famous dome is. But as it was being worked on, people who got a look at it realized this was such a massive unprecedented work, such a glorious work that the city fathers sat down and said, well, we've got to put it somewhere else.

UNGERWe've got to put it in a public space where people can see it. And eventually, it was decided to put it on the platform in front of the government building right in the most prominent spot in the prominent plaza in Florence. And it became a symbol of Florence itself. Florence had long identified with David as the underdog fighting against the stronger enemies. So even before it was done, it was seen as a work of unprecedented majesty and power and as a symbol of the entire nation.

UNGERSo but it's actually interesting. There were factions within Florence who were not very happy with it and as it was being transported -- it took, I think, three days to cover the few blocks from Michelangelo's studio to the piazza, but it was actually attacked, probably by supporters of the Medici who were, at that time, on the political outside, but who resented this great symbol of the Republic.

UNGERSo it was enmeshed in political controversy almost from the beginning.

REHMAll right. Let's go to Atlanta, Georgia, and James. Hi there, you're on the air.

JAMESHey, Diane.

REHMHi.

JAMESA moment with you is like an eternity of bliss.

REHMOh. I'm getting all kinds of good comments today. Thank you.

JAMESYou're the best. Thanks very much for the call. You touched on it a little bit earlier. I'm a little bit confused as far as with the Catholic Church's vociferousness and, you know, homosexuality and homoeroticism, why is there so much of that present versus in the paintings in the Sistine Chapel and how did Michelangelo ultimately navigate around contentious cardinals and all the way up through to the pope to defend his work.

JAMESThanks very much.

REHMThank you.

UNGERWell, that's an interesting and complicated question, partly because it changed during his life. Michelangelo lived through the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation and the counter Reformation. In his early works in the "David" which is boldly nude, even though they ended up actually covering up his private parts with a couple of fig leaves for awhile...

REHMBut certainly not with "David."

UNGERWell, they did. They did. In the end, they actually did cover him up a bit while it was actually sitting there in the plaza. But during Michelangelo's youth, up until the first decades of the 16th century, there was a very easygoing tolerant attitude towards beauty and nudity. When a time comes when he paints "The Last Judgment," the world had changed.

UNGERMartin Luther had nailed the 95 theses to the door at the Church in Wittenberg. The Protestant revolution -- Reformation begins. Europe is torn apart by religious strife. The church is trying to reassert itself. I mean, one of the things that the Protestants rightly attack the church for was it's kind of moral laxity, you know, it's corruption, the fact that popes commonly acknowledge their own children and set them up in important positions so the climate had changed.

UNGERSo when "The Last Judgment" is unveiled, what would've been perfectly acceptable a couple of decades ago was hugely controversial. He was -- there were people who wanted to imprison Michelangelo for heresy and so the tolerance of the early Renaissance really gave way to the intolerance of the Inquisition.

UNGERAs far as the specifically homoerotic element, homosexuality was treated differently in the Renaissance. In fact, they didn't have a word for it. They didn't have a notion of it. In a funny way, they were more tolerant of homosexuality because they considered all sexuality sinful. They didn't simply say -- they didn't simply take this one kind of sexuality and say this is wrong and everything else it right.

UNGERThe only kind of licit sexuality was between a husband and a wife so everything else was sort of put in the category of sin. So Michelangelo believed himself to be a sinner, but there were many other sinners and sinning with having relations with somebody of your own sex is not really that much different from visiting a prostitute.

REHMWas he a religious human being?

UNGERHe was very religious, but in his own personal idiosyncratic way. I mean, he was very tormented by his -- what he considered his own sinful nature.

REHMHere's an email from Evelyn. "Did Michelangelo use models for his sculptures? If not, how did he get the human body right?"

UNGERHe did use models. Often, interestingly, he used male models for female subjects. Sometimes you'll see many of his women look very masculine and -- but he often used shop assistants and other people who were convenient, unlike Rafael, his great contemporary and rival, he almost always drew from male models and then, you know, if he were making a female figure would stick a couple of breasts on them or, you know, otherwise make them female.

UNGERBut yes, he did use models. He also dissected, which was still fairly uncommon for artists. Early in his youth, he went to a morgue and dissected cadavers of paupers and criminals who had died. And he had an understanding unrivaled of not only the surface of the human body, but the way the muscles and joints worked together.

REHMHere's an email from Steven who says, "Many of the stories you've told come from Michelangelo's own biographers, Condivi and Vasari. Can you talk about your own research process and how your biography differs from the large number of recent biographies on the artist? How would you characterize your own critical take on Michelangelo and the still current mythologies about him?"

UNGERWell, I think what I wanted to do in my biography that I don’t think has really been done before is to include a -- to fit the work within a narrative biography. Normally, if you have a narrative biography, it gives short shrift to the work or if you can have biography on the work, that sort of neglects the life. I wanted to find a way to bring the two together to sort of embed the art within the life and to explain the art through the life and also, to a certain extent, to explain the life through the art.

UNGERAnd there are, of course, great resource for biographers for Michelangelo are those two early biographies by Condivi and Vasari, both men who knew Michelangelo personally. In fact, Condivi's is something of an autobiography since most people think that Michelangelo actually dictated it to him. But they told the story as Michelangelo wanted it told and Michelangelo, though he was willing to reveal certain aspects of himself, was not willing to reveal others.

UNGERHe shaped his story to fit his legend and to fit his own sense of himself.

REHMAnd this last part, "how would you characterize your own critical take on him and the still current mythologies about him?"

UNGERMy approach, generally, when I write a biography is to sort of -- simply to write it and see the, you know, the feelings. These are my -- this is my understanding of the work when I go and I see the Sistine Chapel and I go and look at the "David." I certainly have read enormous amounts of the work other people have written.

UNGERI don't really worry about it. I'm sure it's all in there somewhere, but what I'm doing is reacting to the work. How does it speak to me and how do I think it will speak to the people who view it themselves? So I don't really get caught up a lot in sort of schools of thought. I mean, the one area, I think, where I felt a great tension with what other scholars were writing was in the Sistine Chapel and the extent to which this was Michelangelo's own vision and to the extent to which it was -- the program was set up by theologians other than himself.

UNGERAnd I take the, I think, somewhat minority view that this is really Michelangelo's vision that he expressed.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." The idea of "David" and what he represents, you've already talked about in terms of what was happening then and there. Was he satisfied with it once it was finished?

UNGERThat is one of the pieces that he seems to have been satisfied with. There's nothing on record, as there often is, where sometimes he would sort of damage his own sculpture in fury or leave it unfinished. It was finished and by all accounts, he was, you know, it made him world famous so he could've had no complaints from that point of view.

REHMAnd did he make lots of money from it?

UNGERHe did okay. It's hard to say. Michelangelo was always pleading poverty, but he clearly -- towards the end of his life, we was a millionaire and -- he made more money from the popes than he did from the Florentine government, which never had as much money. But it was certainly useful as a stepping stone. It brought him to the attention of Pope Julius who paid him very handsomely for the tomb and then for the Sistine Chapel.

UNGERAnd he ended up being a very wealthy man, though he never thought he was.

REHMAll right. To Jeff in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, you're on the air.

JEFFMorning. Nice to talk to you.

REHMThank you.

JEFFI was just curious if you could talk a little bit about Michelangelo's rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci. I understand that they were contemporaries. I also had heard, at one point -- and I'm not sure if this is true or not, but that Michelangelo was kind of envious of da Vinci's acceptance in some -- more of the society of Florence, which I heard that he wasn't as successful at, so.

UNGERWell, Leonardo was one of the many great men that Michelangelo had difficulty with and felt rivalrous with. Michelangelo, for all his arrogance and pride, was very touchy, very sensitive and somewhat paranoid and jealous of other successful artists. Leonardo was a generation older than he was and was successful first. And he did, when he came back to Florence, to carve the "David," Leonardo was the most famous artist in Europe.

UNGERHe was in Florence at the same time and there is a tale of an argument the two of them got into in which Michelangelo felt that Leonardo had insulted him and Michelangelo snaps back and saying, well, you were the person who couldn't even complete the sculpture in Milan and then sort of walks off in a huff. And Michelangelo's career was marked by such rivalries, with not only Leonardo, but the great architect Bramante, with Rafael whom he regarded as his nemesis and was always thinking Rafael was going around stealing his ideas.

UNGERFor Leonardo, it's mostly the kind of jealousy of an older man who's already regarded as the great man, the great artist of Europe and he did feel insecure and...

REHMYou know, as you have talked about him, his rivalries, his insecurities, his jealousies, it sounds as though those were really part of what was driving him and that's not unusual in today's day and age. Would you agree?

UNGEROh, I agree completely. He was incredibly ambitious, proud, but also what came with that was terribly insecure.

REHMMiles Unger, he's an art historian and journalist. His new book is titled "Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces." Congratulations.

UNGERThank you very much.

REHMThanks for listening all. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.