Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

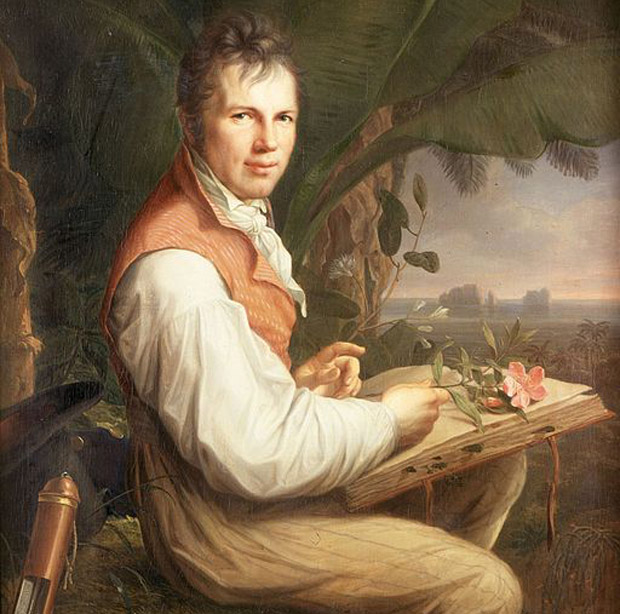

Alexander von Humboldt is shown in an 1806 portrait.

Trekking across Latin America in the early 1800s, Alexander von Humboldt climbed the tallest volcanoes. He paddled down treacherous rivers. And he observed wildlife unknown to his fellow Europeans. Humboldt was the Shakespeare of the scientific world, in his day–famed for his explorations and vivid accounts of the natural world. He is in many ways the founding father of environmentalism: he predicted man-made climate change, and was the first to conceive of the natural world as an interconnected web. And yet he is largely forgotten. Now one historian says it’s time to restore him to his rightful place in the history of science. We investigate the lost legacy of Alexander von Humboldt.

Excerpted from The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf. Copyright © 2015 by Andrea Wulf. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. His name is on mountains, parks, ocean currents and streets and yet today, German naturalist and explorer, Alexander Von Humboldt, has been largely forgotten. Now, historian and naturalist, Andrea Wulf, says his legacy as a pioneering environmentalist whose ideas are still present in modern scientific thinking is more relevant than ever.

MS. DIANE REHMHer new book is titled "The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt's New World." She joins me here in the studio. You are welcome to be part of the program. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or Twitter. Andrea, it's good to meet you.

MS. ANDREA WULFThank you for having me back.

REHMAndrea, I must say when I saw the name Alexander Von Humboldt, I thought who? What? Why a book about this man? Who was he?

WULFWell, let's start with a few facts. He was born in 1769, which is the same year as Napoleon. He was the second son of wealthy Prussian aristocratic parents in Berlin and he became the most famous scientist of his age. So he was so famous that his contemporaries said he was as famous as Napoleon. He was the Shakespeare of the sciences. His contemporaries called him the greatest man after the deluge.

WULFHe was a visionary thinking and scientist and he came up with an idea of nature, which was the idea that nature is a web of life. And he was an extraordinary explorer so he's brazenly adventurous. He went on a five-year exploration of Latin America. And he was so famous that it is almost impossible to think now that he's completely forgotten today.

REHMHow did that happen?

WULFWell, there are many reasons for that. One is that he was really the last of the great polymaths. So he was a genius polymath who roamed across the disciplines and when he died in 1859, which was just a few months before his 90th birthday and a few months before Darwin published "The Origen of Species," that is really a time when the scientists specialized so much that they kind of crawl into their narrowing disciplines.

WULFSo Humboldt is really the very last person almost who can hold all the knowledge of the world in one head. And when he dies, after that, people really -- scientists really start thinking that a polymath is more of an amateur, a dilettante because he is not an expert in any one discipline. So that's one reason. The other reason, I think, which is more important is that his ideas of nature as a web of life, for example, have become so self-evident that almost -- we've almost absorbed his ideas so much that we've forgotten the man behind him.

WULFAnd then, he's, you know, and I like to point out, he is almost forgotten in the English-speaking world. So in Germany, he's very well-known because he was German and Latin America, everybody knows him. He's as known there as Jefferson is known here. And I think the reason why he's forgotten here is because in World War I, the anti-German sentiment is so strong that it's really not a time to celebrate a German scientist.

REHMInteresting. Now, Andrea, you start with this climb that he takes of Chimborazo in the Andes. Tell us about what happened there.

WULFSo Humboldt is on a five-year exploration in Latin America and in 1802, it's the third year, he is crossing the Andes from 2,500 miles all the way north at the coast from what's today Columbia to Lima. And as he's crossing the Andes, he climbs every reachable volcano. And in June, on the 23rd of June, 1802, he begins to climb Chimborazo, which is then believed to be the highest mountain in the world.

WULFIt's almost 21,000 feet high. It's about 100 miles south of Quito and they climb up and they're on this, you know, on hands and knees, they're crawling up this kind of high narrow ridge. And when they look to the left, they see an ice-encrusted steep cliff. When they look to the right, it doesn't look much better. There's a 1,000 foot sheer drop. The icy wind has numbed their hands and feet. Their eyes are blocked shut.

WULFTheir gums are bleeding. They're at about 17,000 feet. They can hardly see anything because thick fog has completely enveloped Chimborazo.

REHMAnd their shoes are virtually nonexistent.

WULFWell, their shoes -- basically, the soles of their shoes are shredded so their feet begin to bleed and they struggle. Obviously, they struggle to breathe in the thin air at 17,000 feet, but they continue. And every few hundred yards, Humboldt stops and he sets up his scientific instruments and he fiddles around with a kind of brass screws with his kind of numb fingers and he measures. He measures everything. He measures gravity.

WULFHe measures altitude. He measures the blueness of the sky. He measures the humidity and he notes everything meticulously. And then, suddenly, the fog lifts and they can see the snowcapped peak of Chimborazo against the dark blue sky, but they also see a huge crevice in front of them and they realize that they can't go any further. They're just above 19,000 feet. And although they don't reach the peak, which is about 1,000 feet higher, they have achieved something remarkable because no one has ever been higher than this nowhere in the world.

WULFSo he holds the world record for several decades. But the extraordinary thing really is that as he's standing on top of the world seeing the kind of mountains folded below him, his vision of nature clarifies and everything falls into place. And there's this extraordinary moment where he -- when he comes down, he sits down and he sketches the mountain with all the plants according to where they grow on their -- according to their altitude.

WULFAnd he realizes that the journey from Quito up Chimborazo was like a botanical journey from the pole -- from the Equator to the poles. So he sees the tropical species in the valley and then as he climbs up, he sees almost the vegetation zones stacked on top of each other. And he realizes that he's seen these plants elsewhere in the world and that there are vegetation zones which are, you know, which are global vegetation zones and he's really the very first to understand that because other scientists are looking through the narrow lens of classification at that time.

REHMAndrea, did you actually recreate that climb?

WULFI tried. Yes. I mean, one of the great things about doing a book about an explorer is that you get to travel to pretty amazing places yourself, obviously all in the name of research. So I went to Venezuela because he went there to the rain forest, but I also went to the Andes because I knew I cannot write about this without having seen it myself, but also without, you know, you need to kind of -- you actually need to feel how hard it is to walk and climb in thin air.

REHMAnd, of course, you were, I presume, climbing with the necessary equipment that he and his team had nothing of.

WULFYes. I had very good shoes because I'd read his diary entries. And we had a guide, of course. And so I went up to Murazo (sp?), but I only made it to 16,400 feet, which is the kind of base camp. And that was hard enough, I have to say. I mean, with every single step you just, you know, every step becomes so heavy and hard and with every step, my kind of admiration for him grew because, I mean, they had terrible weather conditions.

WULFYou know, they didn't have the right climbing gear. And, you know, I was carrying a bottle of water, basically.

REHMI was about to ask what you were carrying.

WULFBut not scientific instruments.

REHMWow. You call this book, "The Invention of Nature." I mean, I think of God as the inventor of nature so how do you mean this by using "The Invention of Nature."

WULFWell, you could've called it the invention of an idea of nature. That would've made a very cumbersome title so I'm obviously not saying that Humboldt invented nature or made nature.

REHMYes, right.

WULFWhat he did is, what I was trying to say with this title is that he comes up with a concept, with an idea, with a vision of nature that still very much shapes our thinking today, this idea that nature is an interconnected whole. He describes Earth as a living organism where everything is connected, you know, from the tiniest insect to the tallest tree. So it's this idea of nature as a interconnected whole that is thumping with life, that's what he comes up with.

REHMAnd he even foresees climate change as being something created by man.

WULFYes. So he is -- basically because he sees nature as a web of life almost like a, you know, as a tapestry of nature so if you pull one thread, he realized that you might unravel the whole thing. So he then makes this kind of prediction that humankind is affecting nature in one way or another and because he sees it in different -- he sees how the forest is destructed and...

REHMAndrea Wulf, she is the author of a brand new book. It's titled "The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt's New World." Stay with us.

REHMAnd welcome back. If you've just joined us, we're talking about the great explorer and naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt. Andrea Wulf, the author of "Founding Gardeners," whom we had on the program several years ago, has written about him to reignite interest in this man's contributions, his understanding of nature, his writings. Her new book is called, "The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt's New World." And rarely, Andrea, have I seen a more beautiful cover.

WULFThank you.

REHMI must say, the design from Knopf is absolutely beautiful.

WULFI know, they did such a beautiful job.

REHMYou must be very happy with it. Here's an email from one of our listeners. Joey asks: Did Humboldt predict the extinction of many animal species as we have seen today?

WULFWhat he -- not -- what he does -- let me start again. What he does is he predicts that, if we go on like this, that the consequences will be catastrophic. And he talks about that -- about a future when humankind might travel to other planets. And he says that we might leave them as ravaged and barren as we're doing already with Earth.

REHMWow.

WULFPretty extraordinary, isn't it?

REHMPretty extraordinary.

WULFAnd he, I mean, he says, for example, what he explains is that humankind affects the climate and the environment in three ways. He says, they do that through the destructions of the forests, through irrigation, and through, what he calls, the great masses of steam and gas in the industrial centers. And see, he says that in 1832.

REHMHow extraordinary. How extraordinary.

WULFYeah.

REHMAnd here we are in 2015 grappling, still, with issues that the industrial revolution has given us, including the use of coal, fossil fuels of all kinds -- still grappling. Here's an email from Will in Adelphi, Md. Did Humboldt ever meet or correspond with Kant or Goethe? How did either of those German icons influence Humboldt?

WULFWell, that's a very nice question to answer because I have a whole chapter about the friendship between Humboldt and Goethe. He -- they were very close. They met in Germany when Humboldt was a very young man -- actually before he leaves to travel to South America. And Humboldt, when he meets Goethe, is very much a child of the enlightenment. So he's interested in reason, in measuring the world. And it's Goethe who was the greatest German poet then, who -- what Humboldt says -- gives him new eyes, gives him new organs to see the world. Because...

REHMWho asked for that meeting? Do you know?

WULFWell, the -- Alexander von Humboldt's brother, Wilhelm von Humboldt, he was living in Jena, which is a small town in Germany. And he was a very good friend with the playwright Friedrich Schiller, who was a very good friend of Goethe. So they all hung out, you know? They were like having dinner and talking and discussing their work. And then whenever Alexander visited his brother, they were all hanging out together.

REHMHmm.

WULFAnd Goethe, interestingly, is not just a great poet, but he was also a scientist. So they were really feeding off each other. And they got on really well. And it was a life-long friendship. But what Goethe gave Humboldt -- and that's what I think made Humboldt so great -- is that he gave him this idea that you should use your imagination to understand nature. You should listen to your feelings. You should experience nature. So Humboldt, in a way, straddles the enlightenment and romanticism. And he does that through these eyes that Goethe has given him.

WULFBut he was also, to answer the next half of that question, he was also -- he never met Kant, but he read his works and he admired him very much and greatly.

REHMI wonder if you had an opportunity to meet any of von Humboldt's descendants?

WULFI have not. Mainly because Humboldt himself never had a family and children. So he never married, he never had children.

REHMHmm.

WULFSo I don't really see him as a family man. He really is a -- as many contemporaries said -- he was a citizen of the world. So it's...

REHMHe was a loner, though.

WULFYes, he was. He was. I don't think you could go on an exploration like he goes on if you are not comfortable with yourself. Although, he had a travel companion, the French botanist Aime Bonpland. But unlike most explorers at that time, they didn't travel with a huge entourage, you know, people who were like schlepping around their beds or something like that. They, you know, they often -- it was just them and a couple of local guides.

REHMSo your earlier book, "Founding Gardeners," somehow has led you to von Humboldt.

WULFYes. Actually it has. There is -- so in the "Founding Gardeners," I talk about the attitude of the Founding Fathers to nature, agriculture and the environment, and how that shaped America. And I had a chapter in that book about Humboldt meeting Jefferson and Madison. Because when Humboldt returns from his exploration in 1804, he just, you know, as you do, there's a little detour to meet Jefferson, who's then president, because he greatly admired him. And I had a whole chapter in the "Founding Gardeners" about this meeting. And then that chapter was kind of, quite rightly, deleted in the edit, because it didn't really have to do much with the story.

WULFBut I got -- because I got so over excited with Humboldt, I wrote this whole thing about Humboldt and, you know, this was a book about the Founding Fathers. So it was kind of deleted. But what happened really is that Humboldt came from Latin America with all these completely new ideas about nature and about the threat to the environment. And he talked to Jefferson and Madison about that. And Madison was so deeply influenced by these ideas that Madison's -- Madison, a few years later, gives this speech, in 1818 actually, where he warns the Americans that they have to start protecting the environment.

WULFSo Madison, in a way, is America's forgotten environmental -- father of environmentalism. But his teacher was Humboldt. And I think this is what this book is really about. It is about Humboldt -- as much about Humboldt, but also about all the people he then goes on to influence.

REHMHe was not very approving of the institution of slavery.

WULFYes. He was a life-long abolitionist. Which really -- this -- you're really hardened when he saw how badly the slaves were treated in Latin America. And it was -- one of the points he always criticized about America -- he adored America for, you know, he was a great supporter of the American Revolution. He, you know, he called himself, I'm half an American. He admired Jefferson. But he never stopped criticizing the institution of slavery. So much so that whenever American visitors came to visit him, he would question them about slavery.

WULFAnd then one of his books, which was a big critique -- a big criticism of slavery -- when it was published in America, the translator left out the chapter that criticized slavery and Humboldt was furious. So he wrote a letter to American newspapers saying, you know, this translation is absolutely not correct. The most important thing in there was my criticism of slavery.

REHMDid he speak directly with Jefferson about slavery? Do we know?

WULFThey did not, as far as I know. I reckon it's this: So there's Humboldt, who arrives in his mid-30's in Washington. He's this explorer. He's kind of famous and not because he's done this kind of mad exploration. But he's not as famous as he will later be. And he writes a letter to the president of the United States, saying, like: Hi, there. Just kind of coming by. Can I meet you? And Jefferson, who has just acquired the Louisiana Territory for the United States in the previous year, is pretty delighted. Also, he'd received a letter from the ambassador in Cuba saying, you should really meet this man. Because Humboldt had spent a year in Mexico, so he was, you know, he came with all this information about the new neighbor, Mexico.

WULFSo Jefferson invited him. But he's still the president of the United States.

REHMOf course.

WULFSo I think that Humboldt did not address this directly to him. But he did address it with -- to other -- with other people who he had met in D.C. So I think he was hoping that Jefferson will hear that. But he also -- excuse me -- he also, later, praised Simon Bolivar for abolishing slavery. And he put that, you know, very publicly in one of his books. He never, obviously, could say something like this about Jefferson. So I think -- I mean, Jefferson must have known how critical Humboldt was about slavery.

REHMAndrea, how long did it take you to research and write this book?

WULFIt's very difficult to say because I kind of started collecting materials such a long time ago.

REHMWhen you were writing the "Founding Gardeners."

WULFExactly. And then I kind of continued. And in between I wrote another book. But I would say I spent the last three and a half years very, very intensely, not doing anything else than this. Because, for once, it was very useful to be German, because I could read all the...

REHMYou grew up in Germany.

WULFYeah. And I could read all the, you know, I could read all the German letters and the German original sources. But it was, you know, it was kind of dealing in a lot of different languages. He has a terrible handwriting, that man. As much as I adore him, his handwriting is awful. But, yes, so it took a -- and because I'm also looking at eight other people he influenced, so I've written like eight mini-biographies about the other people and their -- how Humboldt influenced them.

WULFSo I, for example, Charles Darwin, and then, you know, because no one really has looked at this before, so you have to go through Darwin's letters, seeing when he mentions Humboldt. Or, extraordinarily, we still have Darwin's copies of Humboldt's books, which Darwin took on the Beagle. They're in an archive in Cambridge. And when you open them, you see hundreds and hundreds of pencil marks where Darwin has written into the books. So it's, you know, it's like listening to Darwin having a conversation with Humboldt. But, of course, that takes a long time to read that all. So it's taken me awhile.

REHMAnd you loved every minute?

WULFYes. You know, so much so that I'm feeling -- I'm feeling bereft now that I have to -- well at least I can talk about him still. But it's really strange. It's, for the first time, I'm not so much on a -- I don't feel I'm on a publicity tour about this book. I'm more, you know, I'm more a champion for Humboldt.

REHMA champion.

WULFYou know, I want him to be known again.

REHMWhat did he look like?

WULFHe was very handsome. He, now, he was very, very handsome. He was...

REHMHow tall?

WULFHe was kind of average height. He had kind of this kind of tussled, curly kind of hair. He -- a lot of people remarked about his eyes. He was quite sinewy. So he was not, you know, he was kind of wiry -- strong -- he was physically fit because otherwise you could have not climbed all these mountains. And when you see portraits of him as an old man, in his mid-70s, he's still so handsome. I mean, he's a very good looking man.

REHMHe must have had women who would have loved to be involved with him.

WULFWell, there are -- Dolly Madison says this wonderful thing when Humboldt is in Washington. She says that all the ladies are in love with him.

REHMOh.

WULFAnd it happens all the time. But as far as we know, Humboldt has never had an intimate relationship with a woman. And I'm pretty sure that he was gay. He has a, you know, he has very intense friendship with often younger scientists. And there are quite a lot of remarks by contemporaries which indicate, you know, that these relationships were then seen as quite inappropriate.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." We've got lots of callers. We'll open the phones. 800-433-8850. To Imara in Houston, Texas. You're on the air.

IMARAHello, Diane. And thank you for taking my call.

REHMOf course.

IMARAI'm just so glad that somebody is championing the Alexander von Humboldt. I grew up in Venezuela and (word?) that we learned in school about the friendship of von Humboldt and the independence leader, Simon Bolivar, into that friendship, we learned about him and his feats and what his exploration of Venezuela. Many peaks, roads, and national parks have his name in Venezuela. So I'm so happy that somebody is taking on his feats here in the States.

WULFWell, thank you. You are absolutely right. I was astounded when I went to Venezuela how every single person knows -- I mean, every school child knows his name there. And his friendship with Bolivar is incredibly important because Humboldt's -- it was almost like if Humboldt's writings about the kind of magnificent beauty of South American landscape reminded the colonists just how beautiful their continent was.

REHMHmm.

WULFAnd Bolivar's revolutions really invigorated von Humboldt's writing. And Bolivar later says that Humboldt awakens South America with his pen.

REHMWell, you are awakening North America with your book, I must say, Andrea. Let's go to Jason in East Lansing, Mich. You're on the air.

JASONHi. Thanks so much for taking my call, Diane.

REHMOf course.

JASONI'm a big fan of the show.

REHMThank you.

JASONI was so excited to hear von Humboldt's name on the radio today. I'm a biologist here at Michigan State University. I study electric eels.

WULFAh.

JASONAnd I tell many of my students about von Humboldt's exploits in terms of electric eels that almost became legendary in Europe after he returned. I was just wondering if you could dissect for us the legend versus the actual story with von Humboldt's encounter with the electric eels.

WULFOf course. I'm so pleased. Suddenly, everybody who's calling up, knowing his name. Yes. It is one of my favorite stories about Humboldt. So he was, like many other scientists at his age, very interested in something they called animal electricity. So they believed that animals had some kind of electricity inside them. And he was doing lots of experiments where he would attach metals and chemicals to frog legs and stuff like that. But then -- he did that in Germany. But then he went to Venezuela, to the Llanos, which are these kind of huge plains in Venezuela, and he heard from the locals that there are these extraordinary electric eels living in some ponds.

WULFAnd electric eels are about five foot long and they can discharge voltage of about 600, so very, very dangerous. Now the big problem was like how to get them out of the pond without dying, because you can't just net them. So the locals suggested to drive 30 wild horses into the pond. And now -- so the horses went into the pond, and their hooves which kind of churning the mud in which the eels lived. So the eels, in panic, kind of discharged their voltage. And then they could net them and Humboldt could do all the experiments with them.

REHMWhat a story. Andrea Wulf, her book, "The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt's New World." Stay with us.

REHMIf you've just joined us, we're talking about a fascinating man whose legacy in this country has not been as widely known and joyously received as it has elsewhere in the world, his name, Alexander von Humboldt. And Andrea Wulf, who wrote "Founding Gardeners" and who was on this program back in 2004, has written her new book on him. It's titled "The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World."

REHMIf you'd like to join us, 800-433-8850. Send your email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook, or send us a tweet. And here is a tweet from Joseph. Did Humboldt's conception of nature contrast with different indigenous conceptions that he may have encountered in Latin America?

WULFI get this question very often. It's quite interesting because he -- he's fascinated by indigenous people, and he always questions them, asks them, you know, because he learns a lot from them, and he calls them the best geographers and the best observers of nature. He is not -- so Humboldt's idea that nature is a web of life really, I think, does not come from indigenous people. It's more because he has this incredible memory.

WULFSo a lot of people comment on that, that he can remember the shape of a leaf, for example, or the shape of a rock, 30 years later, and he can make this connection when he's, you know, say he's in Russia, he can remember he's seen something similar 30 years previously in South America. And I think that's why he comes up with this idea that nature is a web of life because he has this incredible memory, and he connects everything.

REHMAnd here's an email from Michael in Tacoma Park, Maryland. Please ask about the tremendous hardships of navigating the Oronoco River and Humboldt's amazing maps of the botanical zones of mountains so far ahead of his time.

WULFWell, he and Bonpland, his traveling companion, they go -- they travel along the Oronoco and the surrounding river network, and they paddle 1,400 miles, 75 grueling days, deep in the rainforest, which of course made for very dangerous traveling. So their boat capsized. They almost starve. They encountered dangerous animals like crocodiles and jaguars and snakes. But they also encounter the most magnificent ecosystem on our planet, the rainforest.

WULFAnd Humboldt was interested in everything. So he looks at plants and animals. He listens to the monkeys, to the, you know, the bellowing cries of the howler monkey. He sees the crocodiles basking in the sun. He sees huge snakes swimming in the water. And there's this incredible moment where he lies awake at night and hears the noise, and he unpeels this chain of reaction, and he describes how the jaguars are chasing the tapirs and the capybaras, who then wake up the monkeys, who are sleeping in the trees.

WULFThe monkeys then wake up the birds. So suddenly the whole rainforest is alive, and he says, he says there -- it is this ever-amplifying battle amongst the animals. He talks about some contest, like a bloody battle. And this is what Charles Darwin then underlines of his copy of Humboldt's book because this is Darwin's idea of the survival of the fittest. So Darwin writes, in the margins, he says how animals prey on each other, what positive check. So it's this kind of extraordinary thing how -- you know, he is so influential because he's out there in nature, and he experiences it.

REHMDear heaven, what would he think of the destruction of the rainforest today?

WULFYeah, he would be absolutely devastated, and I think the terrible thing is actually that he -- you know, he saw so much destruction already, you know, more than 200 years ago. And I think he would be absolutely shocked that we have not done anything to, you know, to do anything about it at all.

REHMLet's go now to Trudy in Rochester, New York. You're on the air.

TRUDYOkay, I'm originally from Germany, and it's so good to hear about Humboldt. You know, there is the old university in Berlin, it's called after Humboldt, and at this university, Angela Merkel's husband, he's a professor. He teaches physics there.

WULFYes, it's the Humboldt University in Berlin, which is actually named after both brothers, Wilhelm and Alexander because...

TRUDYI've been there. You know, I mean, I'm so happy to hear, you know, about some German great people. We have a lot of them, but I'm surprised that never -- that people never heard of Humboldt here.

WULFI know, which is extraordinary, but if you think that in North America alone, there are four counties and 13 towns named after him, there is a bay, the Humboldt Bay, there is a river.

REHMAnd there is even a current.

WULFThere's the Humboldt current, exactly.

REHMWhere is that?

WULFThat's the ocean current hat hugs the west coast of South America.

REHMAll right, thank you for your call, Trudy, and to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, David, you're on the air.

DAVIDYes, I just wanted to mention the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, which brings young scientists from all over the world to Germany to study. And I was the beneficiary of what's called the senior scientist branch, which provides exchanges between the United States and Germany of senior scientists. So I benefitted from that, staying six months at the University of Karlsruhe in southwestern Germany.

WULFYes, that -- and this foundation is very much in line with what Alexander von Humboldt believed because one -- I think one of his greatest achievements was that he believed that science should be accessible and popular but also that knowledge should be free. And he -- you know, all his life he was fighting for that. So as a young man, when he was a mining inspector in Prussia, he opened a mining school to teach miners about geology. He did that, you know, privately funded with his money. And it went on.

WULFSo for example when he was older, he gave these extraordinary series of lectures in Berlin in the early 19th century, which were open to everybody. So you didn't have to pay to get in. So these were lectures where you had the King of Prussia but also servants and students and women.

REHMWhere did his money come from?

WULFHe was the son of a wealthy Prussian family, and when his -- so his father died when he was quite young, and then his mother died when he is in his late 20s, and he inherits a lot of money. He inherits so much money that he can fund this exploration on his own and all his publications, which have these beautiful engravings. But he dies a poor man because he spends all his money on that, and he is completely -- he has completely run out of money when he dies.

REHMHere's an email from Ralph. How recognizable would today's world be to Humboldt? It seems that mankind now dominates most of the land surface of the planet, 7 billion people. Seems as though we're pushing the ecological limits. Did he have any observation on animal population growth or evolution?

WULFSo he is -- he is very interested in evolution without naming it evolution of course. So is called by his contemporaries a pre-Darwinian Darwinist. He talks about nature being in flux. He talks about species changing. And a lot of Darwin's ideas, again when you read through Darwin's copies of Humboldt's books, you can see how Darwin underlines all these things. He kind of finds examples while he's working on his evolutionary theory.

WULFHumboldt is very interested in animal population. He always questions people. He -- and he, for example, there's a wonderful description where he talks about it's deep in the Orient, in the rainforest, where missionaries collect turtle eggs, and they use the turtle eggs, the oil of the turtle eggs, to light their lamps in their kind of missionary churches. But what they do is they collect so many eggs that the population of the turtles are going down.

WULFAnd interestingly, it's the indigenous people who tell Humboldt this. So they give him the number. So the indigenous people already observed that the population of the turtles is going down every year. So he writes this down. Or he talks about, for example, oysters off the coast of Venezuela, which are disappearing because of over-fishing and for pearls. So he's very aware of all these things, and he warns about them.

REHMDoes he also warn about the population of human beings?

WULFHe doesn't because I don't think it was a problem then at all. So he writes down -- he writes down numbers of population, but he's not really concerned with that.

REHMAnd a tweet from Robert. Did Humboldt ever meet Thoreau?

WULFHe did not, but very good question. I have another chapter about Humboldt's influence on Thoreau because he was incredibly influential. What happens is this. Thoreau leaves his cabin on Walden Pond in 1847 and turns these two years into the most famous piece of American nature writing, "Walden." But he struggles to write "Walden." It takes him years. And he writes and rewrites and drafts and eventually he gives up and puts it away because his problem, Thoreau's problem, is that he is observing nature like a scientist but also admiring its beauty.

WULFAnd he struggles to find the balance, and he says, you know, what kind of science robs our imagination? And then he reads Humboldt's "Cosmos," and a new world opens for Thoreau, and he takes out his manuscript for "Walden," and he completely rewrites it because Humboldt says that you have to use your imagination to understand nature. So it's really "Cosmos," Humboldt's "Cosmos," is the answer to Thoreau's dilemma on how to be a poet and a scientist.

REHMJust absolutely fascinating. And to Farmington Hills, Michigan. Hi Roberta, you're on the air.

ROBERTAHi Diane, I love your show.

REHMThank you.

ROBERTAI knew nothing about Humboldt, but now I want -- I will buy that book, and I will read it.

WULFThank you.

ROBERTAHe sounds like he was -- oh, you're very welcome -- a beautiful human being. I look at this portrait, a picture of him on the website, and he looks like he has such kind eyes. And I like that he, as an African-American, that he wrote about slavery. He understood the system within terms of nature and human beings. And I just think he must have been a beautiful human being.

WULFI think you are right, he was a wonderful human being who always spent his last penny on other people, kind of helping struggling artists and scientists.

REHMAnd you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show. And to Jack here in Washington, D.C., you're on the air.

JACKThank you, thank you Diane. About five years ago, I came across a newly published biography called "Humboldt's Cosmos" by Gerard Helferich. I happened to meet the author down in Mexico, where I spent part of my winters, and I inspired by the book. After reading, I was inspired to know about Humboldt, and I reported on the book when I came back to Washington to a readers' group I belong to called The Browsers, and I started by saying, how many of you know the name Alexander von Humboldt.

JACKThere were a dozen people, roughly, in the group. Only one man said, well, my law firm represents Humboldt County out in California. But to get to the point, you've been asked about whether Humboldt met or knew numerous famous people of his time. As you mentioned, Diane, he and Napoleon were exact contemporaries, and Napoleon, according to Helferich, and, by the way, I assume Helferich's book is in Ms. Wulf's bibliography, Napoleon was jealous of Humboldt's fame.

JACKAnd they met only once, according to Helferich, at a reception of some sort in Paris. Humboldt was at the top of his fame. He had returned with all of these plant species from South America, previously unknown, and Napoleon came up to him and said, I understand, Mr. von Humboldt, Herr von Humboldt, that you collect plants. And von Humboldt responded, yes, sir, I do. So does my wife, said Napoleon, turning on his heels and walking away.

JACKAnd according to Helferich, that was their only meeting. I wonder if Ms. Wulf can confirm that.

WULFYeah, so they probably didn't meet in person other than that. And -- but Napoleon was also -- he is very suspicious of Humboldt being a Prussian spy because at the time Humboldt was living in Paris, France was at war with Prussia. So it was a very, very weird thing that a Prussian scientist was living in Paris, and Napoleon did not like that. So he had the secret police spying on him and read his letters, and he was not too pleased.

WULFBut one of the reasons is that Napoleon also was publishing lots of books about Egypt because Napoleon was very interested in the sciences, and that was in direct competition to Humboldt's books about South America. And Humboldt was a little bit more successful. So Napoleon did not like that too much.

REHMI wonder if von Humboldt's looks also intimidated Napoleon. I mean, as you describe him, a tall, live, lean man, Napoleon sort of...

WULFShort.

REHMShorter and stouter, and...

WULFI don't know, I've never thought about that, but maybe. But I think Napoleon had a pretty good self-confidence at that stage because he was just, you know, he's just -- he just became the emperor of France, when they met, basically.

REHMAnd two questions appear. Have you written a book in German because our caller would like to read it in the original German.

WULFI can't write in German, which is a bit embarrassing because I am German, so I write in English, but this book will be translated, not by me, by someone much more capable, to German. But it will only be published in German next year. So you have to wait for another year.

REHMBut how wonderful. Congratulations. And from Gerry in San Antonio, who says, there was an expo in Mexico City 20 years ago with his work. There is now a museum in Mexico City that has some of his original drawings.

WULFYeah, I mean, he is -- he is so famous in Latin America, it's unbelievable that we've forgotten about him here.

REHMAnd one last Facebook comment from Dinah. His memory for leaf shapes and such was enhanced by his field sketches. The book, by Andrea Wulf, "The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World." Congratulations.

WULFThank you so much. It was lovely being here.

REHMThanks for listening, all. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.