Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

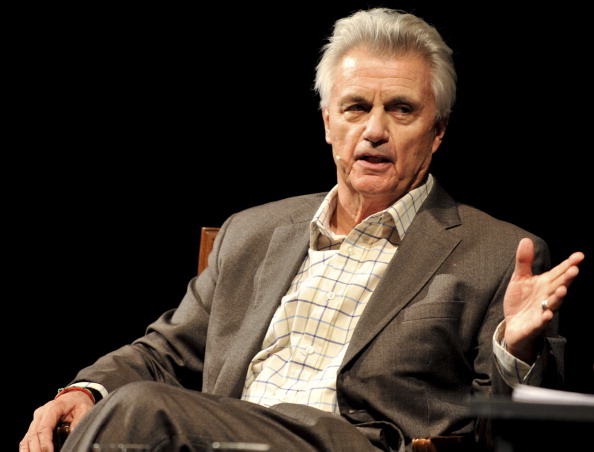

Irving, at an event in Munich, Germany, in 2012.

John Irving has been writing books for nearly 50 years. His latest tells the story of an aging novelist, famous for over-the-top sex scenes and a book about abortion. But don’t call this autobiography. Juan Diego grew up in a dump in Oaxaca with his clairvoyant sister, Lupe. He taught himself to read by scavenging books from piles of burning trash. He later joined a circus and ended up in Iowa. At age 54, Irving’s protagonist embarks on a journey to the Philippines to fulfill a childhood promise. The stories of past and present intertwine to create a vivid exploration of love, death, and miracles. Diane talks to John Irving about his new novel, “Avenue of Mysteries.”

Excerpt from AVENUE OF MYSTERIES by John Irving. Copyright © 2015 by John Irving. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc, NY.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. John Irving is perhaps best known for his novels "A Prayer For Owen Meaney," "The Cider House Rules" and "The World According To Garp." Now, his 14th novel titled "Avenue Of Mysteries," he tells two parallel stories of one man's life. In the past, Juan Diego is 14 living in a dump with his sister Lupe who can read minds. In the present, the beloved novelist and teacher travels to the Philippines to make good on a promise he made years before.

MS. DIANE REHMJohn Irving joins me from NPR in New York to talk about his new novel. It's titled "Avenue of Mysteries." You can join us, 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. And John Irving, it's so good to see you again.

MR. JOHN IRVINGAnd you. Hi, Diane.

REHMThank you. John Irving, this book is really two stories. Tell us about Juan Diego as young 14-year-old and Juan Diego as a well-known and really well respected professor.

IRVINGThe story is told in a back and forth fashion on parallel tracks, which Juan Diego believes are the tracks on which he's always lived his life. The past not only intrudes in his present life, it is the most calamitous and absorbing episode of his life. What happened to Juan Diego at the age of 14 when he and his sister were still living in Oaxaca where they were born, and went to work almost immediately in the basurero, the dump. They are what's called dump kids.

IRVINGNinos de la basura, literally children of the rubbish. But Juan Diego is a self-taught reader and the Jesuits who put such a high priority on education send one of their brothers to meet him in the dump and Brother Pepe persuades the two old priests at the Jesuit temple and the orphanage that these children should be admitted to Ninos Perdidos, Lost Children, their orphanage in Oaxaca to rescue them from service in the dump.

REHMJohn, I wonder if you would read for us that portion that begins on page 5 when Brother Pepe first meets these kids and their dog.

IRVINGBeginning with...

REHMStarting in the middle of the paragraph that begins "but Brother Pepe couldn't see the dog."

IRVINGYes. For how far, Diane, do you want me to go?

REHMAnd take it over to page 7 where you say, "more shelf space for the Jesuit school." Is that okay with you?

IRVINGIt's fine with me, I just can't find the shelf space line. The paragraph begins how?

REHMThe paragraph begins "well, I'm not surprised. It's one of yours."

IRVINGGot it, got it. So you want to end line -- make the end line "to make more shelf space," that'll be a difficult one, "for the Jesuit school." I mean, I should mark that because I'll mess that up. Okay.

REHMOkay.

IRVINGYou ready?

REHMI'm ready.

IRVINGHere we go. "But Brother Pepe couldn't see the dog who was growling so fiercely behind that shack's screen door. He took a second step away from the door, which opened suddenly, revealing not Rivera or anyone resembling a dump -- the small, but scowling person in the doorway of El Jefe's shack wasn't Juan Diego, either, but a dark-eyed feral-looking girl, the dump reader's younger sister, Lupe, who was 13.

IRVINGLupe's language was incomprehensible. What came out of her mouth didn't even sound like Spanish. Only Juan Diego could understand her. He was his sister's translator, her interpreter. Lupe's strange speech was not the most mysterious thing about her. The girl was a mind reader. Lupe knew what you were thinking. Occasionally, she knew more about you than that. It's a guy with a bunch of books, Lupe shouted into the shack, inspiring a cacophony of barking from the disagreeable sounding, but unseen dog.

IRVINGHe's a Jesuit and a teacher, one of the do-gooders from Lost Children. Lupe paused, reading Brother Pepe's mind, which was in a state of mild confusion. Pepe hadn't understood a word she'd said. He thinks I'm retarded. He's worried about the orphanage accepting me. The Jesuits would presume I'm uneducable, Lupe called to Juan Diego. She's not retarded, the boy cried out from somewhere inside the shack. She understands things.

IRVINGI guess I'm looking for your brother, the Jesuit asked the girl. Pepe smiled at her and she nodded. Lupe could see he was sweating in his Herculean effort to hold all the books. The Jesuit is nice. He's just a little overweight, the girl called to Juan Diego. She stepped back inside the shack, holding the screen door open for Brother Pepe who entered cautiously, looking everywhere for the growling but invisible dog.

IRVINGThe boy, the dump reader himself, was barely more visible. The bookshelves surrounding him were better built than most, as was the shack itself. El Jefe's work, Pepe guessed. The young reader didn't appear to be a likely carpenter. Juan Diego was a dreamy-looking boy, as many youthful but serious readers are. The boy looked a lot like his sister, too, and both of them reminded Pepe of someone. At the moment, the sweating Jesuit couldn't think who the someone was.

IRVINGWe both look like our mother, Lupe told him, because she knew the visitor's thoughts. Juan Diego, who was lying on a deteriorated couch with an open book on his chest, did not translate for Lupe this time. The young boy chose to leave the Jesuit teacher in the dark about what his clairvoyant sister had said. What are you reading, Brother Pepe asked the boy. Local history, church history you might call it, Juan Diego said. It's boring, Lupe said. Lupe says it's boring. I guess it's a little boring, the boy agreed.

IRVINGLupe reads, too? Brother Pepe asked. There was a piece of plywood perfectly supported by two orange crates, a makeshift table, but a pretty good one next to the couch. Pepe put his heavy armload of books there. I read aloud to her, everything, Juan Diego told the teacher. The boy held up the book he was reading. It's a book about how you came third, you Jesuits, Juan Diego explained. Both the Augustinians and the Dominicans came to Oaxaca before the Jesuits. You got to town third.

IRVINGMaybe that's why the Jesuits aren't such a big deal in Oaxaca, the boy continued. This sounded startling familiar to Brother Pepe. And the Virgin Mary overshadows Our Lady of Guadalupe. Guadalupe gets short-changed by Mary and by Our Lady of Solitude, Lupe started babbling incomprehensibly. La Virgen De La Soledad is such a local hero in Oaxaca, the Solitude Virgin and her stupid burro story. Nuestra Senora de la Soledad short-changes Lupe, too. I'm a Guadalupe girl, Lupe said, pointing to herself.

IRVINGShe appeared to be angry about. Brother Pepe looked at Juan Diego who seemed fed up with the Virgin wars, but the boy translated this. I know that book, Pepe cried. Well, I'm not surprised. It's one of yours, Juan Diego told him. He handed Pepe the book he'd been reading. The old book smelled strongly like the basurero and some of the pages looked singed. It was one of those academic tomes, Catholic scholarship of the kind almost no one reads. The book had come from the Jesuits own library at the former convent now the Hogar de los Ninos Vedidos.

IRVINGMany of the old and unreadable books had been sent to the dump when the convent was remodeled to accommodate the orphans and to make for shelf space for the Jesuit school.

REHMJohn Irving, reading from his new novel "Avenue of Mysteries." Short break, right back.

REHMAnd welcome back. For those of you who've just joined us, John Irving is on the line with us from our NPR studios in New York talking about his brand new novel. It's titled "Avenue Of Mysteries," which I gather, John Irving began with a series of photographs.

IRVINGI first saw my good friend Mary Ellen Mark's photographs of children in Indian circuses, child acrobats, child performers in those circuses, in the late 1980s, and by the time I went to India with Mary Ellen and her husband, the British born filmmaker Martin Bell, I'd already written a couple of drafts of a screenplay about such children in an Indian circus. It was at the time called "Escaping Maharashtra."

IRVINGI lived with the Great Royal Circus, with Martin and Mary Ellen, for most of the month of January, a little bit into February in the winter of 1990. And for several years Martin and I tried to get a screenplay made in India. We ran up against the censorship of the Indian government, a kind of scrutiny of foreign films, which are held up and examined as to whether or not they shed India in a favorable light. Quite clearly our story did not. These are high-risk children, these child performers, and the argument could be made that whatever risks they take in the circus, their life in the circus might be better than what would happen to them if their lives developed along the lines of their natural course, and the circus never took them.

IRVINGThat's the corner they're painted into. What makes the life in the circuses of India so dangerous for the high-wire act child performers is the fact that in most of these circuses, there is no safety net. Martin and I failed to get our screenplay made in India, and the story moved to Mexico, where Mary Ellen, ever with her camera, found other children, other child performers in circuses there. Martin and I relocated our story in Southern Mexico, Oaxaca principally but also in Mexico City and in a circus outside Mexico City, as well as one in Oaxaca.

IRVINGThe Jesuits, who had always featured in our story, were a better fit in Mexico, and furthermore we discovered that not only in 1970 when we wanted to meet Juan Diego and Lupe at the ages of 14 and 15 in Mexico, but even today, the workers in the dump, the ones who separate the copper, the glass, the aluminum, the plastic, the workers who do that job are children. They were children in 1970 when everything that could be burned in the dump was burned. They're still children now.

IRVINGAnd so this was always a screenplay for many years, until sometime around 2008, 2009 I began to see what would make it a novel, a kind of what if quality that would add 40 years to Juan Diego's life and allow us to meet him for the first time when he was 54, looking 64, feeling at times 74 and on a trip to the Philippines to make good on his promise to a draft dodger he meets when he's 14 in Oaxaca.

REHMAnd in fact he had an accident there in Oaxaca. His foot is crushed, which makes him, in part, look much older than he actually is. And the second fascinating aspect to his story as a young boy in Oaxaca is that his sister Lupe does, indeed, read minds, and that is what the Franciscan, the Jesuit is so taken aback by. He realizes in that conversation early on that this child reads minds.

IRVINGIt's a questionable gift, perhaps, for a child, especially an isolated child like Lupe, who needs her brother to interpret for the rest of the world what she says. It's a burden to bear, if you think you know the future, and you're that young. Whether you're right or not about what you think you know, if you believe you see what's coming, this can affect how you behave. And if you're frightened of the future you see, why wouldn't you, even at some risk, attempt to change it?

IRVINGLupe of course has ancestors in earlier novels. Lily in "The Hotel New Hampshire" believes she sees the future. She commits suicide because of it. Owen Meany in "A Prayer for Owen Meany" believes he sees his on future. He's mostly right. But what he's wrong about, what he doesn't see, is what the principle story of that novel is. And Lupe is a character with these ancestors. It's the third time now I've given to one of my characters at least a partial view of what I always know as a novelist, writing as I do, ending-driven stories, stories which always begin for me with a stronger grasp of what happens at the end of them than I have yet determined as to how to begin them, well, it's tempting at times to give one your characters a sense of his or her own predetermination, which I always have, which I always know.

REHMWell, and that was the question I was about to ask you. I wonder if at times, given the fact that you've now invested this ability within three of your characters, whether somewhere inside John Irving is not that same feeling of being able to read people's minds, not just creating characters with that ability but feeling that ability within yourself.

IRVINGWell, I don't think the way my fiction works can be applied to what I presume my abilities are in so-called real life. My own real life, my own actual life, has been uneventful. My novels are for the most part worst-case scenarios. I try to imagine characters that I hope you will feel sympathetic to, even love, and once I make you like them, I make you worry about what's going to happen to them because something always does.

REHMJuan Diego is a young man who not only reads Spanish from the books he pulls from the dumps, reads them also in English. He learns. He teaches himself to read English. He reads to his sister. Some of these books are dull, as she says, boring. Others teach him about life. Where is their mother?

IRVINGEsperanza, who is perhaps in her own case incorrectly named for hope, is a cleaning woman for the Jesuits, quite a good one, but she has a night job, arguably more lucrative than that of being a cleaning woman for the Jesuits, their temple, their orphanage, their school. Esperanza is also a prostitute, and the exact determination of who Juan Diego's father and Lupe's father is...

REHMOr are.

IRVINGRemains for much of the novel unclear. It's unclear. There's always this suspicion that Rivera, the dump boss, could be, might be, probably isn't, Juan Diego's father, but under no circumstances are we supposed to believe that he could be Lupe's father. Lupe imagines, of course, she has multiple fathers, which is a misunderstanding on her part. What she really means is that whoever Esperanza was sleeping with at the time Esperanza got pregnant with Lupe, there are too many possible fathers to count. But by then she was no longer, everyone agrees, sleeping with Rivera.

IRVINGSo the determination regarding who's Lupe's father and who's Juan Diego's father remains for a long time unknown, and in Lupe's case will continue to be unknown, suitable to her preternatural gift of clairvoyance.

REHMJohn Irving, we're talking about his brand new novel. It's titled "Avenue Of Mysteries." If you'd like to join us, 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or Twitter. And we do have a Facebook comment from Kat, who is a singer/songwriter who says, I wish I had a brilliant question for him, but I'd simply like to express my thanks to John Irving. His novels have brought me respite, joy, laughter and tears. His command of words moves me to be a better writer myself. Our world is improved by his work. She ends by saying, thank you John. And you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show."

REHMThe idea of these two young children, John Irving, and how they live and where they live and the encounters they have, I found myself wondering and worrying about where their food came from before the Jesuits came along.

IRVINGWell, I think as Lupe says, when Pepe wants the orphanage Lost Children to take these children, Lupe doesn't want to go. She thinks the dump boss is not only better than a father, he's more than enough. He takes them shopping. He cooks. They cook. He really does provide for them. They're certainly the two best provided-for kids among the dump kids in the Oaxaca basurero. They're very well-looked-after by the head of the dump himself. In fact, Brother Pepe says to Juan Diego that he should hope, he should wish that Rivera was his father, which Juan Diego does.

IRVINGSo I don't think we ever feel that the kids are starving or deprived. Rivera does the best job he can looking after them. But the perception that they're workers, which they are, pepenadores, which means scavengers in the dump, really compels the Jesuits, especially the missionary from out of town, Edward Bonshaw, the new arrival in Oaxaca, who finds it intolerable that these children work in the dump, and how can Juan Diego work in the dump after Rivera's truck backs over his foot, and he becomes so severely crippled.

IRVINGIt is the instance of Juan Diego becoming crippled that drives the Jesuits to take the children from the basurero and relocate them in the orphanage Ninos Peditos.

REHMAre they relocated together?

IRVINGWell, much against the rules, they are allowed to stay together. The Jesuits give them a former reading room in the orphanage school. They even have their own bathroom, an unheard of luxury. In other cases among the orphans, even brothers and sisters are separated. There are ostensibly girl dormitory facilities and boy dormitory facilities. But because Lupe is so dependent on Juan Diego to be her translator because no one can understand what this child says, however clairvoyant or prescient she indeed seems, however articulate when Juan Diego does translate her she is. After all, she has more exposure to adult language from books than she has from actual communication with real adults. She still is incomprehensible and cannot be separated from him.

REHMJohn Irving. The book is titled "Avenue Of Mysteries." Short break. Right back.

REHMWelcome back. John Irving is my guest. He has a brand new novel titled, "Avenue of Mysteries," just out. If you'd like to join us, 800-433-8850. John Irving, we have an email from Arnold, in Burke, Va., who asks, "Were you at all influenced by Gunter Grass's novel, 'The Drum,' in which a midget interrupts for the reader?

IRVINGI think I was more than influenced by Gunter Grass's "The Tin Drum." I read that novel and I was a college student, studying abroad in Vienna. It was a year of study in a German-speaking country. I made what I believe is a very direct act of homage to Grass in "A Prayer for Owen Meany." I gave my character, Owen Meany, the same initials as Oskar Matzerath. Oskar Matzerath has a voice that shatters glass. Owen Meany's voice is strange and does other things.

IRVINGNow, here's another character with a strange voice, Lupe. I think no novel -- certainly no contemporary novel I read as a college student, a very influential time in the life a want-to-be writer, I don't think there is a contemporary novel that influenced me as much as "The Tin Drum." (Inaudible) was hugely important to me. Grass and I later became friends. I gave one of the eulogies at his funeral last May in Lubeck.

IRVINGAnd I miss him. The books I read that made me want to be a writer, largely 19th century novels, I feel greatly indebted to. And you could look at "Avenue of Mysteries" as an act of homage to another great German writer, Thomas Mann. Had I called this novel "A Death in Manilla," I might have given more away than I wanted to. Although, I think it's clear that Juan Diego is a troubled, not-well man, a heart condition, the medications which he's loose and relaxed about taking.

IRVINGAnd I think most readers will sense that this journey to the Philippines might be his last. But if I'd wanted to be more obvious about that, speaking of homage or influence, I could have called this novel, "Death in Manilla."

REHMIndeed.

IRVINGBecause it's very much a tip of the hat to Gustav Aschenbach in "Death in Venice." Very much so, yes.

REHMAnd, of course, you did mention that you spoke at Gunter Grass's memorial or funeral service. And in that, I'm reading here, you said, "I did not escape his criticism. Yes, Gunter could be critically of me. One night in New York, this was after we had dinner, when we were saying goodnight, I thought he looked a little worried. Not an unfamiliar look, but he surprised me. He said he was concerned about me. He told me, you don't seem quite as angry as you used to be. This was in the '80s. Naturally, you say, I have tried to be angry ever since. I'm trying." Do you consider yourself now an angry man?

IRVINGThere aren't as many things that make me angry now as there seemed to be when I was a younger writer, in my 30s and 40s. "The World According to Garp" is a very angry novel. It's a reaction to my sizable disappointment with so-called sexual liberation, gay and straight. My reaction, my disappointment to the so-called sexual revolution, where we were all supposed to be free and end up loving each other. It was a reaction to how much sexual hatred I saw in the '70s, in the mid-'70s into the late '70s, how much sexual hatred, especially mistreatment and marginalization of sexual minorities still prevailed.

IRVING"The World According to Garp" is a sexual assassination story. A woman is killed by a man who hates men. And her son is murdered by a woman who hates men. It's a pretty extreme take on the sexual hatred that was still bubbling like something in a cauldron, something in a pot, after we were supposed to have learned something…

REHMAnd…

IRVING…about treating -- yeah.

REHMAnd how do you see the state of sexual hatred or sexual acceptance now?

IRVINGBetter, certainly. But if I thought it was good enough I supposed I wouldn't have written, in the case of my last novel, the novel I did. I suppose I would have not written in one person if I felt the business of giving sexual minorities their due and giving them all our respect was as good as it could be or should be. Is it as good as it could be or should be? Absolutely not. Are women still treated as second class citizens? Everyone who wants to ban a woman's right to choose, everyone who wants to ban abortions are still essentially relegating women to the role of childbirth, whether they choose to have children or not.

IRVINGThat certainly is a way of treating women like minorities and treating them as if they deserved to be. I still feel that very strongly. But generally, I don't know. That remark, of course, about Gunter is a little tongue-in-cheek. His anger I feel was exemplary and stood as a model, at least to me. But I certainly have found good use for mine, I hope. You know, I don't hit people or abuse anyone. I try to focus. What upsets me about human behavior and society's constraints and various lack of compassion for people, I try to focus those things in my writing.

REHMAll right. We have many callers. I want to open the phones now. First to Vicky in Miami, Fla. You're on the air.

VICKYHi, Diane. Thank you so much for your shows this week. I am over the moon with your interviews with my favorite writers, Stephen King and John Irving.

REHMGood.

VICKYMr. Irving, I have a two-part question for you. First, I am Filipino and that's one of the things that tipped me to purchase your book yesterday. I wanted to know your favorite, favorite things about your trip to the Philippines a few years ago. And my second question is I wonder if you ever, like I do, wonder about some of your characters from your (unintelligible). I wonder about particularly Ruth Cole and whether she's still happy with her Dutch cop. And thank you so much. I'll take my answer off the air.

REHMAll right. Thanks for calling.

IRVINGWhere would you begin with that one, Diane? Give me a hand.

REHMWell, I think she wants to know about your trip to the Philippines, what you thought and whether you'd go back.

IRVINGYeah, that's -- that was the most -- that's the most -- thank you for your -- what you said about my writing. As I am distracted by the Philippines question because it's a difficult one to answer in that I go almost nowhere, truly. I go almost nowhere for pleasure, recreation or to be a tourist. I went to the Philippines with a family from there, close friends with my wife and youngest son. But -- how can I make you understand this? I did not go as myself. I was thinking about my character, Juan Diego, who had left Mexico at age 14 and never gone back for understandable reasons.

IRVINGI was thinking about his trip to the Philippines that I wanted him to take in this novel. And the whole while I was there, when I was by myself, which I was much of the time, I sat and took notes about the things I'd seen and the things I'd done, not as if I were the person responding and reacting to those things, but asking myself always, how would this man whose life was so affected by what happened to him as a 14-year-old in Mexico, what would he feel by this visual sight, by this smell, by this experience. And so I was there taking notes for a character in a story.

REHMIndeed.

IRVINGOne I had thought about for years.

REHMAnd you would not go back therefore?

IRVINGWell, okay. I love the company of the friends I went there with. I loved the food. But every once in a while I'm sure everyone was disappointed with me. My wife and son, too. And they said we're going to see the volcano. And I'm sitting there thinking to myself, Juan Diego's not here to see the volcano. I'm not going to see the volcano. That's not what Juan Diego sees. That's not what's going to be a stake in his heart.

REHMAnd the other question she had is whether you recall your characters, wonder where they might be now, do they continue to live?

IRVINGYeah, I've felt I should address the question about my feelings in the Philippines. I thought I should say, you know, when I'm traveling somewhere for something I'm writing. I'm not myself.

REHMIndeed.

IRVINGI'm in my story and in those characters. Conversely, I can't tell you how Ruth Cole and Harry are doing. I stopped thinking about them when they hooked up and when Marion came back and said don't cry, honey, it's just Eddie and me. When Marion says don't cry, honey, it's just Eddie and me, I stopped thinking about Ruth and Harry. I'm done. I never think about them anymore.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." And an email from Guadalupe saying, "How much of the novel is based on real events? Or is it all fiction?"

IRVINGWell, the title of the novel itself, "Avenue of Mysteries" avenidos de los misterios, is, of course, the name of the street in Mexico City that leads to the Basilica, to Our Lady of Guadalupe. All of the material about the Guadalupe story -- the actual Guadalupe story is indeed real. The scrutiny that my character Lupe makes of the most virgins in Oaxaca, the Soledad virgin and Guadalupe, among others, is indeed based on real virgins are of prominence there.

IRVINGThe background material is real. All the orphanages mentioned in the novel, save my fictional one, Ninos Perdidos, all the orphanages are indeed real. And their origins came about as I described them. The places in the Philippines are indeed real. Everything is real. There is a Guadalupe Church in Manilla. And it was always my idea that Juan Diego, that's where he was going. He doesn't know that he's going there, but that's where he was going.

IRVINGHe thinks he's going to pay his respects to the good gringo's father in the American cemetery and memorial in Manilla, but that's not why I sent him here.

REHMWhose name he doesn't even know.

IRVINGWell, it's a sentimental journey, as he imagines it. Of course, it doesn't end up being such. But his reasons, this older man, his reasons for wanting to make good on his absurd promise made to a tragic draft dodger in a bathtub when he was only 14, and the draft dodger himself was in his 20s, a romantic and heroic seeming figure to Juan Diego at 14, that he would presume he should or could make good on this ridiculous promise he made to this desperate young man is an absurd premise. How can he find a man without a name in a cemetery so vast and so full of dead soldiers?

REHMAnd that's where we'll have to leave it. John Irving, as always, a great pleasure to talk with you. John Irving's new novel is titled, "Avenue of Mysteries." Thank you for being with us.

IRVINGThank you, Diane. Thank you, again.

REHMAnd thanks to all of you for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.