Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Guest Host: Derek McGinty

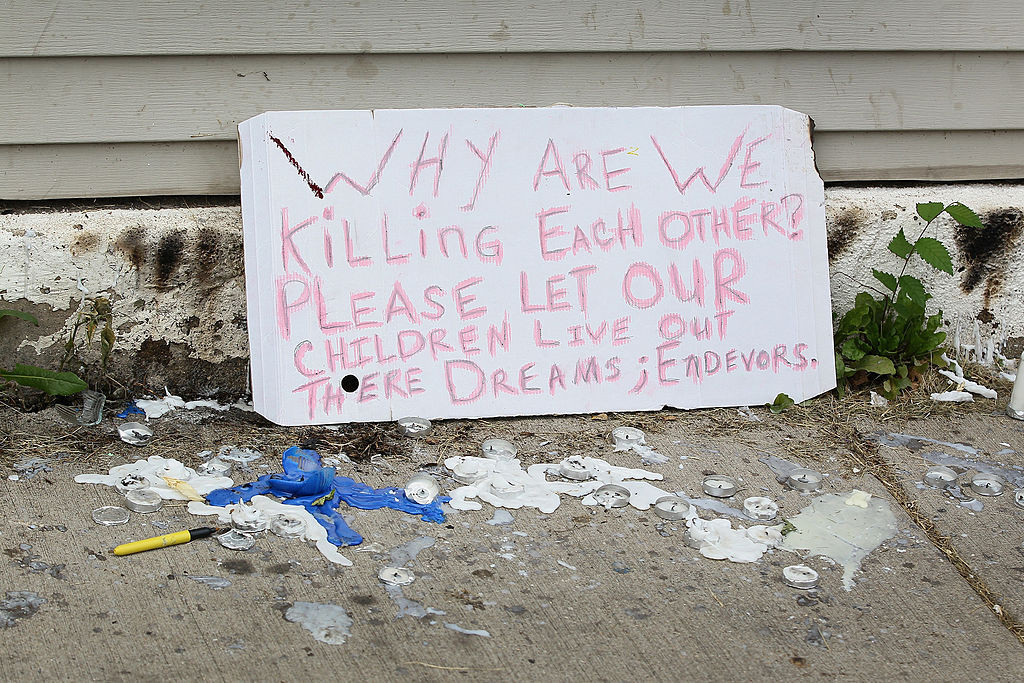

CHICAGO, IL - JULY 20: A sign from a memorial service for Shamiya Adams on July 20, 2014 in Chicago, Illinois. Adams, 11, was killed when a stray bullet flew through an open window and struck her in the head. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

On November 23, 2013, nearly a dozen children and teens were shot and killed in the United States. This did not happen in a mass shooting, but in cities, suburbs and towns across the country – like San Jose, California, where best friends played with a gun they thought was unloaded; Charlotte, North Carolina, where a disagreement escalated to gunfire; Dallas, Texas, where a case of mistaken identity left a 16-year-old dead on the street. These stories do not make this day remarkable. In fact, they make it a pretty average day in America. A new book tells the stories of these young people, and explores what their lives – and deaths – reveal about our country’s relationship with guns.

Excerpted from Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge. Copyright © 2016 by Gary Younge. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

MR. DEREK MCGINTYThanks for joining us. I'm Derek McGinty sitting in for Diane Rehm, who is out in Los Angeles today getting a lifetime achievement award from the International Women's Media Foundation. Well, every night of the week, local news brings a cavalcade of death and despair right into our bedrooms, where we are often overwhelmed and then perhaps numbed by the carnage. Perhaps that is why it took an outsider, British journalist Gary Younge, to take note of one deeply tragic statistic, that is on any average day in this country, seven teenagers and children will be shot to death.

MR. DEREK MCGINTYComing from a country where even the police often don't carry firearms, Younge found America's relationship with guns confusing, troubling even, but even more confusing still was how these violent deaths largely went unreported. That, he felt, was almost as great an offense. So Younge chose one day at random and chronicled the lives of every person who died by gunfire on that day. The result is a book called "Another Day in the Death of America," and Gary Younge is here in the studio.

MR. DEREK MCGINTYI also want to welcome your phone calls, and you can join our conversation at 800-433-8850. Gary Younge, welcome.

MR. GARY YOUNGEThanks very much for having me.

MCGINTYYeah, good to have you here. What hipped a Brit to our violence problem?

YOUNGEWell, it was the statistic, the statistic when I first heard it, I thought, that can't be right, and then you realize it is right, and then you start pursuing -- well, you know, okay, let's just take last Saturday, and then you, you know, you start looking up what happened last Saturday, and you just think, this is -- how can this be?

YOUNGEAnd I lived here for 12 years, and America, it doesn't have any worse parents than Britain does, doesn't have any -- its kids aren't worse than Britain's are. It has -- or anywhere else in the world, it has pretty much all of the same issues, segregation, inequality, poverty, that other -- racism, whatever, that other countries have. Other countries have gangs, too.

YOUNGEBut this seemed particular, and so I wanted to -- and yet if you live here, even if you are just here for 12 years, that kind of statistic is kind of overwhelming. So I thought, well, who are these people, and I spent 18 months finding their teachers, preachers, parents, anyone who would talk to me.

MCGINTYNow you picked one day at -- was it a random choice?

YOUNGEIt was a random choice.

MCGINTYWhat was that date?

YOUNGENovember the 23rd, 2013.

MCGINTYAnd you just said this is going to be my day?

YOUNGEThis is going to be my day, that's right.

MCGINTYAnd okay, let's begin. Well, how did you begin to dig into who died that day, where they died?

YOUNGEWell there's no central -- there is a central statistic of the CDC, but you have to wait a while for them to collate, and they don't -- they collate the numbers, they don't collate the names or anything. So it was internet searches. I'm pretty confident that while there were 10 children who died that day, I'm pretty confident there were more. Two of the seven children who die on an average day are suicides, and those tend not to be reported. So I got all the -- these were all the ones I could find.

YOUNGEAnd yeah, if you pick a different day, you get a different set of kids, you get a different, a different type of the kind of banal fact of death in America.

MCGINTYBut broadly speaking, who were these kids?

YOUNGEOnce again demographically, seven were black, two were Latino, one was white, but actually as human beings, they were for the most part very, very ordinary kids. We're talking Minecraft, Xbox, smuggling girls into their room, you know, not doing what their parents asked them to duty, Call of Duty, big appetites, sexual experimentation, some of them learning to drive. They were America's youth.

MCGINTYWe will get into some of the individual stories here, but one of the points that you seem to want to get across in the book, and you just mentioned part of it, was these kids are not that unusual. These weren't necessarily the best kids, but they were not the worst kids.

YOUNGEThat's right. I mean, there are a couple of kids in there that would, you know, that would make your eyebrows rise of the 10, and I think as a society, what's important is to ask, well, how did they get that way, but that for the most part, and this in a way is the kind of central desire of the book is to create some empathy. Statistically if you're wealthy, and if you're white, and certainly if you're white and wealthy, then statistically these are unlikely to be your kids.

YOUNGEBut if you read this book, and you find out who they are, for better and for worse, and there's no sugar-coating, are they so different from your kids? Are their parents so different from your parents, from parents that you know or from yourself? So there's one boy in particular, just as an example, Samuel Brightmon in Dallas, who's out at 11:00 in a working-class black area of Dallas called Pleasant Grove, and he is -- he's shot. Nobody knows why. He's walking with a friend.

YOUNGEAnd one of the first comments on the news story, he got 90 words or so in the local paper, Dallas Morning News, one of the first comments was, you know, well I know where my kids are, and you've got to ask about these parents and what these parents are doing. And then you find his family, and then you find that Samuel was playing Uno and cheating, watching "We're the Millers" and drinking cocoa with his friend, who was in Pleasant Grove to go with his granny to church the next day, and he decided to walk his friend back, six minutes, six-minute walk, and he was shot during that time.

YOUNGESo on the one hand there's this person who has conjured up an idea of a feral young black male roaming the streets, and then there's Samuel, who cheats at Uno, which is probably about the worst thing he did that day, who was killed for no good reason, whose mum knows exactly where he is, but she just can't save him.

MCGINTYAnd the other side of that story, though, is Stanley Taylor in your book, and I found this very moving. You talked to his mom, and she says over and over again, I tried.

YOUNGEI tried, yeah, she said that. I tried to keep him home, I moved, I -- you know, I grounded him, I scolded him, I tried. You know, and Stanley is 18 years old, he's a bit of a tearaway, but he's not, you know, he's not a terrible kid. You speak to his -- the teacher, Mario Black, who taught him at primary school. He said, you know, he -- by no means was he the worst, and he was kind of straightening himself out.

YOUNGEYou speak to his friend Trey, who is at university, and Trey's, like, yes, you know, Stanley could be aggravating sometimes, but, you know, he was fine. He gets into an altercation at a -- at a gas station. Someone pulls up, nearly runs him over, words are crossed, and then the man, Demontre Rice, who has since been convicted, shoots Stanley, and he dies.

YOUNGEAnd his mom is -- knows that in a sense, and this happens to a lot of the -- particularly the black parents, that they're blamed for their children's death. Not only do they have to deal with the grief, but they have to deal with the sense that outside people think, well, you know, what's wrong with you that you couldn't look after your child. And she's saying, look, I did everything I could to keep Stanley safe.

YOUNGEAnd one of the really shocking things for me, and I'm a black parent, and my children are American, they were born here, and we are -- I only just moved back to England last year, I have an eight-year-old and a three-year-old, nine-year-old and a three-year-old, and was that every black parent that I spoke to, when I say to them, said to them, did you think this could happen, to a person, they said, well, of course, of course you factor that in.

YOUNGEYou know, Samuel's mum in Dallas said, well, I didn't think it would be him. I thought it would be his brother. A father in Newark who died, maybe a few hours after Samuel, said you're not doing your job as a black parent in Newark if you don't think your child could be shot. And that really, that really hit me.

MCGINTYDo you find that the accusation that these parents aren't doing their jobs, from the people you talked to, is unfair?

YOUNGEI did actually. I did -- I show up, usually out of the blue, I say I want to talk to you about your child, and these are parents who can tell you what games their children like playing, what shows they like to watch, can talk about, you know, the earliest memories, who are incredibly -- three of them, of whom I only spoke to two, two of them are -- three of them were single fathers. And no, they were very kind of, for the most part, they were very, very engaged, loving parents.

YOUNGEI know a lot of parents who are a lot richer who farm the childcare out to the nannies and -- or send their children to residential private schools who know a lot less about their children. So -- and I also just don't think Americans make worse parents than British parents. So whatever the problem is, it's -- it can't be parenting because then there would have to be some deficiency in the American way of parenting that makes that possible.

MCGINTYYou think the problem is guns.

YOUNGEI don't think it's the only problem, but I think that -- or the only issue, but I think that if you have this big pile of tinder, which other places do, inequality, racism, segregation, poverty, mental health crises, all of these things, and then you put the easily available -- easy availability of firearms on top of that, that's a very combustible mix.

MCGINTYGary Younge is a journalist from Britain. He has written a book called "Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of 10 Short Lives." I'm Derek McGinty, and you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show.

MCGINTYWelcome back to "The Diane Rehm Show." My name is Derek McGinty sitting in for Diane. And my guest this hour is Gary Younge. He's a journalist and he's from the U.K. But sitting -- being in this country for the last dozen years and watching our gun violence unfold in front of him prompted him to write a book about it. It's called, "Another Day in the Death of America." He chronicled ten short lives, all taken on one day. Tell me the date again.

YOUNGENovember the 23rd, 2013.

MCGINTYNovember 23rd, 2013, ten lives gone. You all -- these are all boys. But you say it -- most days it wouldn't be.

YOUNGEYeah. On an average day -- this is a random day -- on an average day, of the seven children that were shot dead every day, two would be female.

MCGINTYRight.

YOUNGEAnd also three would be black, three would be white, one would be Latino. So this, in all sorts of ways, because it's random, it's not representative. There are more black kids in this than there would be. There are less white kids than there would be. And there are no women, which is unusual.

MCGINTYAs a journalist, one of the toughest things I have ever done is to go up to a parent who just lost a child and say, do you have something you'd like to say?

YOUNGEHmm.

MCGINTYHow did you do that over and over and over again?

YOUNGEIt wasn't easy. And it was also difficult because there was a lot of shoe leather in this book, there was a lot of, a couple of times, literally just walking around a number of possible addresses and putting notes in every door, flying across the country and doing that, and hoping someone got a hold of you. Here's what I would say to their parents. I know how your child died. I would like to know how they lived. Everything you would like to tell me about them, I would like to hear.

YOUNGENow, here's why, of the ten children who were shot dead that day, eight of them, I reached their kin. And here's why I think that worked, was that for so many of them, they -- if they were lucky, they maybe got 600 words in the paper and a quote from their families, but that was it. So you have to imagine, you've borne a child and buried a child. They've left the planet and your local newspaper -- because beyond the local newspaper, it doesn't make news -- gives one quote from you, say, he was a lovely kid and he liked to play basketball or something. And here someone comes and says, I want to know more.

YOUNGEAnd so, for the most part, a lot of these parents felt that their child had died and nobody cared. And so here was someone who had an interest. There was an interesting thing I saw on Facebook the other day. One of the boys who died, Edwin Raho in Houston, whose mother is an undocumented migrant from Honduras, came in an 18-wheeler truck, doesn't speak any English. Her daughter translated -- and a friend, translated for me. And her daughter put Edwin's -- each chapter is a child's name -- and she put the opening chapter of Edwin's thing on her -- on his Facebook page, which is still open, and said, you know, Edwin's in a book. And it was clearly a kind of validation of who he was.

YOUNGEBut then comes the heartbreaking thing. In the comments, one of their friends said, he should write a chapter about Pico (sp?). And so somebody else has died...

MCGINTYHmm.

YOUNGE...that they know. And she says, yeah, I think he was just doing one day. But I can bet you, you know, cents on a dollar that nobody wrote about Pico.

MCGINTYWhat did you want people to take away?

YOUNGEI wanted them to, first of all, stare this statistic in the face. And that the way to present that statistic is to put the people on it, to say that these are not numbers, these are people. But then the second thing was that there was empathy, that these -- they may not be you, depending on who it is that's reading it, but this is not a different species of people that this is happening to. These are your fellow Americans. These are human beings.

MCGINTYYeah. That is, I think, one of the critical points that comes out of your book, and that is that folks may think that this could not happen to them and maybe it is very unlikely, but these folks are no different from you. One of the criticisms about the black community is that fathers are not as involved as they should be. And you suggest that's a myth.

YOUNGEWell, yeah. That was one of the interesting things in doing the research, I found that there were these scripts that people would say. And I would try and check them out. So people would say, you know, it wasn't -- people of around my age, I'm 47, say this -- it wasn't like this in my day. In my day, they would evoke the ancient art of pugilism. You know, we would duke it out.

MCGINTYRight.

YOUNGEWe would have fights. Everyone would go home. Nowadays, babies having babies, people pulling out guns. And so then you go and check. And it turns out that for the most part, people who are saying that, the murder rate was higher when they were growing up, because it was during the crack epidemic. That teenage pregnancy is going down. And then I find the statistic, a government statistic about black fathers -- well, about fathers, that African-American fathers are more likely than fathers of any other race to bathe, read to and eat with their children when they're under five years old. And I'm thinking, how can that be? You know, and I'm checking and I'm double checking.

YOUNGEI'm a black father. I do all of those things. And yet, somehow, I was rehearsing those scripts too. There's another one that people use quite often, which is black-on-black violence. And then you do the research and you find out that violence, like much of American life, including religion, is segregated. And there's white-on-white violence, white people are most likely to commit violence against white people. Latinos, most likely to commit violence against Latinos. Everyone in this book who -- where we know the assailant, is killed by someone of the same race.

MCGINTYYeah.

YOUNGEAnd so black-on-black violence would better just be called violence.

MCGINTYBut I've got to push back a little bit about this fatherhood issue.

YOUNGEMm-hmm.

MCGINTYBecause if you look around, and even if you just look at pictures of some of these scenes, the thing that I'm struck often by is, where are the men? Right? Where are the men? There are kids of both genders.

YOUNGEMm-hmm.

MCGINTYBut the adults you see around are often mostly women.

YOUNGEYeah. And so you're right, that when you look around anecdotally -- and this was the challenge that I had is that you have these anecdotes. But then I go out to find there's ten kids that got shot dead that day, three of the kids are raised by their fathers...

MCGINTYMm-hmm.

YOUNGE...one white kid and two African-American kids. And then, suddenly, when I read that statistic, it doesn't kind of, you know, it doesn't look quite so crazy. Now, it's also true that African-Americans are less likely to stay married. And the African-American men are less likely to live in the same house as their partners, as a result of them not being married. But yeah, I found the statistics very challenging, because my assumption was otherwise. I was raised by a single mom. So I am not inclined to give any men a break who abandon their children, I don't care what race they are. But I found that statistic intriguing. And it wasn't mine.

MCGINTYIt is intriguing for sure. Gary Younge is with me. His book is called "Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives." The phone number here, 800-433-8850. And Gregory from Naples, Fla., thank you for waiting, sir.

GREGORYHello. Am I on?

MCGINTYYou are on.

GREGORYOh, okay. Good morning. My name's Greg Gold. I'm from St. Louis and live in Naples, Fla., now. I think I have an interesting background with the gun issue and the violence. I grew up around guns, being a hunter, and my parents were, you know, my parent was a hunter. But I also -- hello?

MCGINTYHi, there, we're listening to you, man.

GREGORYI've got -- I had apartment buildings in the inner city in St. Louis for 40 years. So I observed a lot of this -- the crack cocaine, the music, the love of guns and shooting each other. I turned the corner before and saw cars rolling to a stop with the glass tinkling out and guys across the front seat gurgling, being shot in the chest. I've seen people being shot and thrown in cars. My take on all this, after obviously thinking about what the hell's going on, is it's a societal problem. It's the availability of guns.

GREGORYIn some ways, they were more readily available when I was growing up than they are now. You could actually buy them out of the back of a magazine simply by signing that you're not a convicted felon and send in a money order for 30 bucks and you get a handgun.

MCGINTYSo when you say societal problems, you mean in terms of our attitudes toward the use of weapons and human life.

GREGORYCorrect. Movies, music, just -- you can't flip through the TV without cops running around shooting at each other or at least with their guns drawn.

MCGINTYYou know, but...

GREGORYAnd they're -- and it seems like every other movie out of Hollywood is -- this latest one with -- it's called "The Accountant," with what's his name, Ben Affleck, where he's an assassin.

MCGINTYYou know, let me stop you there, Greg. I want to give Mr. Younge a chance to respond.

YOUNGESo then, here's my question to you, Greg, is Hollywood comes to Britain. These games, Call of Duty, whatever these games are, they come to Britain. Like I said, Britain has poverty and inequality and all of the kind of things that you're talking about. Why -- if it's societal, why do you think no other society can produce anything like the statistics?

MCGINTYWell, is there this American mythos around violence and, you know, the frontier culture and all of that? I mean, is it gangsters and all that? It's all part of our cultural heritage, isn't it?

YOUNGEWell, (laugh) I mean, you could say that. Australia is a frontier culture. Canada is a frontier culture. New Zealand is a frontier culture. Even Israel doesn't have -- Israel is a frontier culture. It doesn't have this level of gun death. And then, if you look at Britain's history of violence in Kenya, in India, in, you know, large parts of Africa -- or France, Belgium certainly in the Congo -- none of these things are particular to America I don't think. I think the one thing that is particular to America is the free and easy availability of guns.

YOUNGEAnd what I say in the book and I really emphasize, because I think the Second Amendment comes up twice in the whole thing, this is not a book about gun control. But it is a book made possible by the absence of gun control.

MCGINTYYou know, I wonder if, as Americans, we've gotten so used to the guns, the access to them and the fact that it seems there will be nothing done about it and there's nothing that can be done and -- you know, I've often argued that the gun lobby has won this fight years ago -- that we've just kind of put in the background as something we have to deal with. And when you come in from outside and you look at it and you go, why are you dealing with this?

YOUNGEWell, I mean, that is one of the things that I did find. And I am -- this book is not polemic. I'm not out to bang that drum particularly. But the -- I ask everybody, every parent, what do you think this is about? And when I asked that open-ended question, none of them mentioned guns.

MCGINTYReally?

YOUNGEIt just doesn't come up. And I figure, and this really goes to your point, that it must be a bit like traffic. That if your child was run over, you wouldn't say, you know, what? We have to get rid of traffic. It's time. You might argue for a stop sign or for a speed bump. But then, if you did, no one would say that was unconstitutional. You'd be fine. But that -- when I asked them the more leading questions, what do you think of guns? Then most of them said, well, I think it's crazy that they're so easily available and so on and so forth. But when you ask the open-ended question, it just doesn't come up.

MCGINTYGary Younge, his book is called "Another Day in the Death of America." I'm Derek McGinty and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Let's run back to our phone calls. You know, in fact, I want to talk about a Facebook comment we got here, which says, let me see here, we need to teach firearm safety in all public schools. Teaching fear instead of respect of firearms is counterproductive. People start blaming guns instead of criminals for criminal acts.

YOUNGEYeah. I mean, first of all, not to sound like a broken record, we have criminals in Britain. You know? But we don't have anything like this -- that you can say guns don't kill people, people kill people. You can say that. But still, the fact is that guns kill people much more efficiently than anything else that's commercially available. On the day of Sandy Hook, a mentally ill man in China went into a school with a knife and he didn't kill anybody, because it's much harder to kill people with a knife.

MCGINTYHe stabbed a bunch of people but he didn't kill anybody.

YOUNGEHe didn't kill anybody. And in a country where there are lots of guns, it -- there should be, you know, people who have guns certainly should be taught gun safety. But one of the stories in the book is about, in rural Michigan, there's a boy, two boys at a sleepover. They're 11 and 12. Tyler and Brandon, I call them. Brandon is left at home with loaded guns in his house. His dad's a trucker and he's off trucking. And he's showing Tyler the gun and the gun goes off and shoots Tyler dead.

YOUNGENow, however much safety -- they teach bicycle safety at school, children still get run over. They teach Driver's Ed, but young drivers are still more likely to have accidents. That you can teach gun safety, but you're teaching gun safety to children with a lethal weapon.

MCGINTYMm-hmm.

YOUNGEAnd so there's a limit to what you're going to do with that by itself.

MCGINTYSo at this point, do you think Americans are right to just treat it as, as you say, as traffic?

YOUNGEWell, it's a very high price to pay. I mean, that can only be right if seven children a day is a tolerable number. I don't think it is.

MCGINTYAll right. Let's go to Natalie in Gaithersburg. You're on the air.

NATALIEHi. I just wanted to make a comment about what the gentleman said earlier about the specifics of a black father and that kind of how you were dubious about, you know, where are the black men? I'm 32 years old and I'm very much aware of how black men are perceived or portrayed in the media. But all of my friends, whether they're married to their child's mother or not -- these are all young, black men, and this is about 15 to 20 of them that I went to high school with -- they're all involved in their children's lives. I do not have a single male, black friend who is not in some way, shape or form either living in the home or totally co-parenting and involved in their children's lives.

NATALIEAnd I think that there is an interest in the American media in portraying black men as though they're somehow not involved, when, in actuality, they are. Thank you.

MCGINTYAll right. Thank you for the phone call, Natalie. I hope you're right. Well, we are talking with Gary Younge. His book is called "Another Day in the Death of America." And we're taking your phone calls at 800-433-8850, 800-433-8850. I'm Derek McGinty. We're going to get back to more of your calls when we come back. You're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show."

MCGINTYWelcome back. I'm Derek McGinty sitting in for Diane Rehm as we continue our conversation on Gary Younge's new book, "Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of 10 Short Lives." And one of the points you make in the book, Gary, is that though some may want to blame the people involved for what happened, you say if you took 10 upper-class kids and plopped them down in this neighborhood dealing with these issues, some of the outcomes would not be all that different.

YOUNGEWell, right. I mean, the one thing that everybody in this book has in common is that they're all -- they're all working class. They're not all poor, but they're all working class, and if you're wealthier, you have the schools, you are ferrying your kids around, you have the after-school programs, you may have a good YMCA, there's a range of things that you -- that, you know, young people can do in your area.

YOUNGEIf you're in some of the areas where these kids are growing up, that just doesn't exist, so then they're on a corner. Well, if these -- if you took a group of wealthy kids, and you said, okay, this is going to be your life, well, where are they going to congregate, where are they going to hang out. I mean, one of the other interesting facts that I learned was that when it came to drug use, African-Americans were more likely to use crack cocaine, but every other drug, white Americans are more likely to use than they were.

MCGINTYCould you make the argument that black Americans are still more likely to be arrested for using those drugs, and perhaps that accounts for some of the absence of the black men we were discussing?

YOUNGEOh yes. Well, that's -- it certainly does. African-Americans are much likely to be criminalized and to get longer sentences, and, yeah, and to be jailed, but they're not actually more likely to use drugs. And so, you know, part of the answer to the question you were asking before, where are the black men, well, an awful lot of them are in jail for actually not living lives in many ways that are that dissimilar from their white counterparts.

MCGINTYJohn in Howard County, Maryland, thanks for waiting.

JOHNYes, sir. Are these statistics per capita? Another thing is what day of the week was this survey taken on lives, only the question?

YOUNGESo on average, seven children are killed, are shot dead every day. So I mean, do the math quickly in my head, that would be 2,500 or something a year. So that's the average. So it's not like every day that definitely happens, some days more, some days less, and this was on a Saturday, and that was deliberate that -- because some days it is more, and some days it's less. I didn't think the book had any validity unless there were seven kids who got shot dead because that's the average.

YOUNGEAnd so to make sure that that was possible, I did it on a Saturday, a Friday, Saturday or Sunday. That said, children are more likely to be shot dead in the summer, when they are out, and school is out, and it's warm, than in the winter, and this was in November. So this is late fall. So it's -- so it's seven on average, and this was not an average day, and I own that completely.

MCGINTYSpencer in Charlotte, North Carolina, you're on the air, Spencer.

SPENCERYes, if you look at the Home Office statistics, which covers England and Wales, you'll find that the violent crime in England is 3.5 times higher than that of the United States. The gun violence has been falling in the United States for quite a number of years, keeps getting lower every year. And if you take around five cities that are in the United States out of the mix, then the United States' gun violence goes down to around position 111 out of all of the countries in the world, modern countries in the world.

SPENCERYou will -- and if you look at the statistics, you will find that most of the violent crime occurs in populations of 250,000 or greater.

MCGINTYSo what's your overall point there for us?

SPENCERMy overall point is people in Britain, they're running into houses in the daytime, hot burglaries. These people can't protect themselves.

YOUNGEWell hang on because I actually make this point in the book, actually. I say Britain is a more violent country. In my experience, Britain is a more violent country. People get drunk, you go to the town where I grew up, just outside of London, on a Friday or Saturday night, people are drunk, and they will run around, and they can be quite violent. It's just less lethal. It's less lethal.

YOUNGESo while it may be more violent, less people die. Now as to hot burglaries and people breaking in, well here's the thing. If they don't have a gun, if fewer people have guns, then people need -- feel the need for guns. So it's not even comparable the level of gun deaths in anywhere else in the Western world. It's not even comparable.

YOUNGEAnd then to your final point, if you take away the cities, well, if you take away the cities, what are you left with as a country? I mean, the cities are part of America. It's like saying if you extract, you know, the black people, or if you extract, you know, if you extract New York, L.A., Chicago and St. Louis, then you actually are extracting a big chunk of America.

YOUNGENow the point I am not making in this book is that Britain is better than America, or anywhere else is better than America. But the point I am making in this book is that this is unique to America. In no other country in the Western world is this possible.

MCGINTYLet's go to Oklahoma City, Mel, you're on the air.

MELYes, hi, first I'd like to say I appreciate you humanizing the violence or the consequences of violence on this book. I think that's very important. Obviously I have not read your book, but from the things I hear you say, I think your conclusion is not necessary in part because you're comparing apples to oranges, and I'll make this point with this. You are an outsider, and I appreciate that perspective, but I'm also an outsider, I'm originally from Brazil, and I live here in Oklahoma City.

MELAnd Brazil has very strict gun laws, but it only affects law-abiding citizens because criminals don't care, and the violence there is horrendous. And so if I'm to go with your premise, one could make the case that the stricter gun laws, say like in Brazil, might be the cause for violence, and of course I don't believe that, but my point is, I don't think your conclusion is necessary.

YOUNGEYeah, that's why I'm careful to say, compare it to other Western countries. I actually think comparing America to Brazil is comparing apples to oranges. I think comparing America to Britain and the rest of Western Europe and the kind of -- the countries that America generally does compare itself to is a more -- is a more reasonable comparison. And my guess is, I don't know this for sure, but my guess is that the rate of gun deaths per capita in Brazil is probably lower than America, that's my guess.

MCGINTYLet's get to Bill in Orlando, Florida. You're on the air, Bill.

BILLYes, sir. So I just wanted to comment and say that I think that there's other extenuating cultural factors here in our country. I think there's a very, very high sense of competitiveness, and I think that we teach children that they, you know, they can be anything and do anything and achieve anything that they want.

BILLWe have this very sort of, you know, open-ended culture that anyone can become president, right, anyone can become whatever they want to be, and so -- you know, and we glamorize people like Donald Trump, that, you know, basically gets what he wants through a systematic way of bullying, you know, and that's his way of making a deal, right. So I think that that's what we're teaching children, and I think that because we have easy availability of guns, for the most part, you know, when it comes to people that are of a criminal mindset, they're going to go for the thing that's going to get them the result that they want.

MCGINTYBack to the cultural issues again.

YOUNGEI mean, here's -- here's one thing I want to emphasize and that I think is interesting from a lot of the callers is that the book actually really, really isn't about gun control. It is about a country without gun control. It wouldn't be possible in a country -- in a Western country with gun control. But it's interesting -- I mean, I feel like, and this doesn't so much relate to the previous users, previous caller as many others. At the end of the day, seven children are dying -- are being shot dead, and either you want to do something about that or not.

YOUNGEAnd so the various ways of talking about, you know, Britain or Brazil or this or that doesn't -- doesn't bring these kids back, doesn't give their parents any solace. And by the time, you know, today or tomorrow is over, another seven kids will have been shot dead. And so finding ways to explain why they're shot dead doesn't deal with the fact that they are being shot dead.

MCGINTYYou've recently, as you just mentioned a few minutes ago, moved back to the U.K., and as you noted, guns are not nearly so pervasive. Do you find that you feel safer? Do you find that you feel less worried about your children?

YOUNGEWell yes, in relation to one of the previous callers, you know, I have two American children and an American wife. I have skin in this game. So I -- here's something that happened while we were in -- visiting a friend in Derbyshire in kind of hill -- kind of hilly country. We don't have guns as toys in our house. So what that means is that my son then just goes to other people's houses and plays with guns as toys, right, because he likes playing.

YOUNGESo he -- the child in this house has guns as toys, and they go running outside with these -- with these guns. And my wife, who's African-American, looks at me, and we are both -- we're thinking Tamir Rice, we're thinking, you don't let your child outside with a toy gun. And then there was a moment of relief or realization, and I say to my wife, actually it's not ideal but it's going to be fine because nobody is going to assume that's a real gun because nobody has -- people don't have real guns around here, and so nobody's going to assume it's a real gun, and even if they did, they're not going to have a gun to shoot him with.

YOUNGESo while we'll have to have that conversation, it's not the situation that we think it is.

MCGINTYWow, that's intense. Gary Younge's book is intense, it's called "Another Day in the Death of America," and I'm Derek McGinty. You're listening to the Diane Rehm Show. Let's go to TD (PH) in Fort Wayne, Indiana. You're on the air, TD.

TDYes, Derek, first I just wanted to say it's great to hear your voice again. You were one of my best friends back in the early '90s.

MCGINTYOh thank you, TD.

TDI just wanted to say I don't want to make assumptions about your guest, but based on some of the things he said, I think the reason he has some problem with gun violence in this country is he doesn't believe that the right to bear arms is a fundamental human right, which is a cornerstone of our society. You know, if you don't believe it's a basic human right, that's going to affect your views of gun violence.

TDBut the question I've had is, talking to my colleagues in Canada, they say that guns are just as prevalent there and just as easy to get, but again, they don't go around shooting everybody all the time. And I was wondering why he thinks there could be a difference between us and Canada.

MCGINTYInteresting question.

YOUNGEYeah, I mean, first of all, you know, you said I don't believe in, you know, the right to bear arms. I'm not American, so, you know, there's a range of things that I'm -- it's not kind of called upon me to believe. But I do believe, and I think you probably also believe, that children should be allowed to grow up without fear of being shot dead, and there is nothing more complicated about this book than that, really. So it's...

MCGINTYBut also the Canadian situation?

YOUNGEWell, so it's possible to -- I think it's an important point to weight that belief. You have a belief in a fundamental right to bear arms, you have to weigh that belief, or you have to have in that same space, anyway, even if you're not going to weigh it, the fundamental right of children to grow up. I think -- I think it's unlikely that guns are as easy to get in Canada, actually, as America. I think Canadians have more gun control. And beyond that, I think it's the kind of -- I think that all of those things that I talked about, inequality, racism, segregation and so on, which are barriers to empathy and which create the kind of -- happy, wealthy people are unlikely to run around shooting each other.

MCGINTYI want to go back to the first point you made regarding gun rights and the cost of them. What you seem to be saying is, have your guns, have your right to bear arms, but understand that this is the cost of that.

YOUNGEWell the -- no one's going to listen to a Brit, no matter how long they have been here, talk about the Second Amendment, and I have not been talking about the Second Amendment. But I can talk about children. I can do that and -- and that to say Second Amendment as the answer to these 10 stories and the seven that will come tomorrow and will come the day after that, I think that is an inadequate response.

YOUNGEI think it is like referring to ancient scripture, to scripture, as a justification for doing what you do. The Second Amendment does not say seven children should die every day. So then if you're not going to deal with guns, deal with whatever it is that you have to deal with that saves these -- that saves these kids, my kids, who are American kids.

MCGINTYFascinating conversation, a fascinating book, really, "Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of 10 Short Lives." Gary Younge, thanks for writing it, and thanks for bringing it to us.

YOUNGEThank you.

MCGINTYWe appreciate the conversation. This has been Derek McGinty. I've had a great time this week guest hosting on the Diane Rehm Show. She is off in Los Angeles getting a lifetime achievement award, much deserved for Diane. In the meantime, though, we're going to say goodbye now, and I hope you enjoyed the conversation.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.