Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

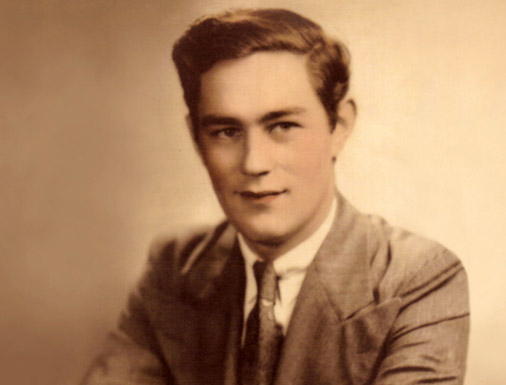

Henry Gustav Molaison, known as "patient H.M.," was unable to form new memories after he underwent a surgery at age 27.

Ever since journalist Luke Dittrich was a boy, he’s known the story of patient H.M. — or at least the textbook version. In the early 1950s, Henry Molaison received an experimental brain surgery to alleviate his epilepsy. It left him unable to create new memories. Over the next 50 years, Molaison underwent a battery of tests, leading to much of what we know about memory today. It was Dittrich’s grandfather who performed the initial surgery. And as Dittrich began to explore his family’s history, a much darker version of the story emerged. Dittrich talks with Diane about a story of mental illness, medical ethics and the most studied brain in history.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. In 1953, Henry Molaison underwent a radical brain surgery for epilepsy. The operation left him altered. He could remember many things from his past, but was unable to form new memories. Over the next 50 years, researchers probed the depths of Molaison's brain and he became known to the outside world as simple Patient HM. For journalist Luke Dittrich, the story is personal. His grandfather performed Molaison's initial surgery.

MS. DIANE REHMResearch into Molaison's life lead Dittrich to a dark era in medicine and his own family's history. Luke Dittrich joins us on the studio to talk about Patient HM, his book subtitled "A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets." I do invite you, as always, to be part of the program. Give us a call on 800-433-8850. Send an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or Twitter. It's good to meet you, Luke.

MR. LUKE DITTRICHIt's so good to be here. So nice to meet you.

REHMThank you.

DITTRICHThanks.

REHMLuke, tell us the story of HM before he underwent any surgery while he was still a little boy.

DITTRICHRight. Yeah, long before he was Patient HM, he was Henry Molaison. He was, you know, a boy who grew up in Hartford, Connecticut, and one day while he was walking home from a park when he was 8 or 9 years old in the mid-1930s, he got knocked down by a bicyclist. He hit his head very hard and it knocked him unconscious. He came to about five minutes later. Not long after that he began suffering from seizures, small ones at first. They grew progressively worse in frequency and severity until by the time he was about 15 or 16, he was, you know, pretty catastrophically epileptic.

DITTRICHIt was a debilitating condition for him. He, you know, they wouldn't let him walk across the stage at his high school graduation because they were worried that he would a major seizure and cause a scene. It was -- it incapacitated his social life as well as his professional life. And by the time he was 27, still living at home with his parents, his parents very sort of fairly poor family. His father was an electrician. His mother worked usually as a housekeeper. His parents were desperate, desperate to find any sort of solution to this, you know, terrible condition that their son suffered from.

DITTRICHAnd my grandfather, who was a renowned neurosurgeon, he was the director -- the head of neurosurgery at Hartford Hospital. He taught neurosurgery at Yale. He had a stellar reputation. He offered them hope. He told them that were was an experimental operation he could perform on their son that might alleviate or cure his epilepsy. And he performed that operation on Henry. He removed several central portions of his brain from both sides, bilaterally, including his hippocampus. Most of his hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, uncus.

DITTRICHAnd Henry, you know, it didn't do much for his epilepsy, but it obliterated his ability to create new memories.

REHMTell me, was this story part of your family lore as you were growing up?

DITTRICHYes, it was. It's one of those stories that I was -- I can't remember -- it's sort of funny. I can't remember the first time I heard the story or at least the sort of the textbook version of the story. I feel like I've known the basics forever and I've also -- I can't remember not being fascinated by it. It's one of those stories that I think even if I didn't have this personal connection to it, I would've been sort of captivated by the story, you know, amnesia, memory, how memory works, human experimentation.

DITTRICHAll of these subjects are ones that I find sort of endlessly fascinating regardless.

REHMAbsolutely.

DITTRICHBut with the personal connection, it became irresistible. You know, as long as I knew that I wanted to be a writer, it was sort of one of those stories I felt like I needed to...

REHMReally.

DITTRICH...tell someday.

REHMYou wanted to tell.

DITTRICHYeah.

REHMThat's really something. Read for us, if you would...

DITTRICHSure.

REHM...from the beginning of the book, starting in the middle of page 12.

DITTRICHSure. "There were things Henry loved to do. He loved to pet the animals. Bickford Healthcare Center was one of the first Eden alternative facilities in Connecticut, which meant that, along with its 48 or so patients, the center housed three cats, four or five birds, a bunch of fish, a rabbit and a dog named Sade. Henry would spend hours sitting in his wheelchair in the courtyard with the rabbit on his lap and Sade by his side. He loved to watch the trains go by. His room, 133, was on the far side of the center and from his window, several times a day, he could watch the Amtrak rumble past the abandoned red brick husk of the old paper mill across the street.

DITTRICHHe loved word games. He's sit for hours and hours and work through books full of them. Many of the scientific papers that have been written about Henry over the past six decades describe his avidity for crossword puzzles, though in his later years, he found them too great a challenge and started doing simple find-a-word puzzles instead. He loved old movies, Bogart and Bacall, that era. "The African Queen," "Gone With The Wind," North By Northwest." We call them classics, though, of course, they were not classics to him.

DITTRICHHe's ask to see one of these movies and a nurse or attendant would pop in a video cassette. Television sets were no shock to him, TV being a technology that developed during his time, but he never did figure out how to operate a remote control. He loved talking to people. He'd tell them stories. He told the same stories over and over, but he always told them with equal enthusiasm. When people asked him if he remembered meeting them before, he'd often tell them that, yes, he thought they'd once been friends.

DITTRICHHadn't they gone to high school together? Even when his uncertainty about these sorts of things frustrated him, he usually remained courteous and cheerful, compliant, too. When the scientists would come to pick him up and take him to the laboratory, he never objected and he almost always took his meds when the nurses asked him to. On the rare occasions that he refused, the nurses knew of an easy way to get him to cooperate. It was a trick passed down over decades from one nurse to another.

DITTRICHHenry, a nurse would say, Dr. Scoville insists that you take you meds right now. Invariably, he would comply. This strategy worked right up to the end until Henry died. The fact that Scoville had died decades before then and that they'd had no contact for decades before that made no difference. Scoville remained an authority figure in Henry's life because Henry's life never progressed beyond the day in 1952 when Dr. William Beatrice Scoville, my grandfather, removed some small, but important pieces of Henry's brain."

REHMAnd that is Luke Dittrich reading from his new book titled "Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets." How long was he institutionalized?

DITTRICHWell, he, himself, was not institutionalized. He lived, after the operation, for many years with his parents. And then -- and I believe it was 1982, he moved into this facility, the Bickford Healthcare Center, which was an assisted living, not a nursing home.

REHMI see, I see.

DITTRICHBut he wasn’t, strictly speaking, institutionalized.

REHMSo he could wander at will. He could engage with other patients. Had the epilepsy ceased?

DITTRICHThe epilepsy had not ceased and in fact, you know, one of the, you know, one of the last papers written about Patient HM found no clear evidence that the surgery had done all that much to actually alleviate his epilepsy.

REHMAnd yet, neurosurgery has a fascinating history going way back.

DITTRICHIt sure does. Yeah. I mean, you know, one of the things I look at in the book, I go all the way back to ancient Egypt where you have some of the early known pieces of human writing are actually these sort of neuro -- proto kind of neurosurgical texts written by the ancient Egyptians. And then, you know, there's this sort of, you know, grand sweeping history of neurosurgery that reaches kind of several climaxes in the 20th century where it, you know, they began going deeper and began performing far more sort of radical operations than had ever been performed before.

REHMAnd that's exactly what I wanted to ask about your grandfather's proposal to operate on Henry Molaison. What proof was he going by? What theoretical notion did he have about the elimination of Henry's epilepsy?

DITTRICHWell, there had been -- the structures that he targeted in Henry's brain, for several years prior to the operation he performed on Henry, other surgeons had been targeting these structures, but they would always go unilaterally. They wouldn't go bilaterally, which is what my grandfather did. So if they removed just one-half of, you know, from one hemisphere of the brain and they left the other hemisphere intact, the idea was that they wouldn't be destroying obliterating whatever the function of those areas was.

REHMAll right. We'll take a short break. More of this fascinating story of Patient HM after a short break. Stay with us.

REHMAnd welcome back. Luke Dittrich is with me. He's written a new book titled "Patient H.M.," subtitled, "A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets." He had known from a very early age that his grandfather had actually performed an operation on Henry Molaison, one that he, the surgeon, hoped would help alleviate or even cure the kind of frequent epilepsy seizures that Henry Molaison was experiencing.

REHMLuke, Henry had the operation that your grandfather performed at age 27. He lived for 55 more years.

DITTRICHRight, and he lived those 55 years with the, you know, the present moment just constantly was sliding off of him.

REHMThat does that mean?

DITTRICHWell, it means that he would have -- the events of his life would not stick. He could have a conversation with somebody, and he might seem on the surface, you know, normal, you might now know that anything was wrong with him, and then you might step out of the room and come back in, and he's introduce himself to you, having no recollection of ever having seen you before.

DITTRICHIt means that he -- you know, he lived a life very different from any life we can really imagine. He had only the vaguest sense of the passage of time. Over the years one of the -- you know, he was repeatedly questioned about how old he thought he was, and as he grew older, into his 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, you know, his answers would -- you know, sometimes he would say I think I'm in my 30s, sometimes in my 40s, and then, you know, you'd hand him a mirror, and he'd look in it, and he'd, you know, sort of look into his own then-elderly eyes and just say I'm not a boy.

REHMWow. What about life with his parents after the operation? Did he continue to recognize them on an ongoing basis, or was there something changed?

DITTRICHRight, he did recognize them. He -- his -- the type of amnesia that he suffered from was largely -- it was actually sort of a combination of both, but it was largely anterograde amnesia, which means that it sort of -- the moments after the operations are the moments that do not stick, the events after the operation. He still had basic memories from before the operation, although those also were, you know, affected quite -- in quite serious ways, as well. But he certainly recognize people he had known from before the operation. He knew his parents very well.

DITTRICHAnd he had memories from, you know, from moments in his life prior to the operation.

REHMAnd then the question becomes, how did the operation affect your grandfather.

DITTRICHRight, well that's -- that's a great question. There's a woman named Brenda Milner, who is a neuropsychologist at McGill University, brilliant, brilliant person who did the sort of the seminal work with Patient HM that the -- sort of the foundational work with him that really taught us a lot about how memory works. And I asked her, you know, did my grandfather ever feel guilty, and she said that no, she didn't think he felt guilty about Patient HM, though she did bring up then another case, a case very similar to the one of patient -- an operation very similar to the one he performed on Patient HM that he performed actually after he had performed the one on Patient HM.

DITTRICHAnd he only discovered after performing the operation that the person he'd performed the operation on had been a medical doctor himself and was rendered also sort of catastrophically amnesiac and that that really shook him, that that was that much more than Henry shook him.

REHMDid you know your grandfather?

DITTRICHI did know him. He died when I was nine years old. So -- and he was -- you know, he was this -- I guess this is true of a lot of grandfathers, but he certainly, in my life, he loomed large.

REHMOf course.

DITTRICHAnd he was this very charismatic guy. There was New York Times writer once described him as almost unreal in his dashing appearance. He owned this sort of rotating fleet of sports cars. He was a world traveler, an adventurer. You know, I'd say, you know, sort of, you know, some people would call him reckless in a variety of ways but very -- yeah, I mean, a very powerful personality.

DITTRICHAnd that's what he was to me, and in fact I'd say, you know, I've spoken with a lot of people in the course of researching this book who knew him, and I'd say that he actually was that sort of character in a lot of people's lives.

REHMDo you think he was reckless surgically?

DITTRICHThat's a very good question. I -- you know, it's very -- I try not to engage in presentism, right. It's easy to kind of look down our noses on what people were doing 10 years ago, let alone six decades ago. Those were very different times. I -- I have to say, though, that there was -- this was a time when -- and this was not just the case for my grandfather but for most of the leading neurosurgeons at the time. They sort of straddled this weird gray zone between medical practice and medical research.

DITTRICHAnd I think a lot of, you know, lines were crossed that shouldn't have been, and I think he crossed lines that shouldn't have been.

REHMAnd you think about the number of lobotomies that were done during that era.

DITTRICHWell yes, and my grandfather, and this is one of the things that I sort of excavate in the book, my grandfather was one of the world's most prolific lobotomists. And the -- it's really impossible, actually, to understand the operation he performed on Patient HM without understanding this long and fairly dark period of so-called psycho-surgical experimentation that led up to that operation. My grandfather, you know, spend decades in, you know, the back wards of asylums performing hundreds upon hundreds of lobotomies on people.

REHMAnd what were they supposed to achieve?

DITTRICHLike a lot of sometimes, you know, horrifying things, they grew out of very desperate times. This was -- if you were mentally ill in the 1930s, 1940s, early 1950s, in the United States or anywhere in the world really, you didn't have an easy go of it. The treatments that were available were limited, and in some cases they were themselves devastated. I mean, there were all sorts of shock treatments.

REHMShock treatments, yeah.

DITTRICHNot just electroshock treatments but insulin shock, Metrazol shock. There were all sorts of treatments that may or may not have actually left you, you know, worse off. The lobotomy presented itself in the late 1930s as a kind of magic bullet, as this quick fix for this intractable and sort of eternal problem that is mental illness. And so -- and it had what appeared to be a very sort of solid scientific footing. It grew out of -- Yale University is actually sort of the epicenter of the lobotomy.

DITTRICHThe first lobotomists took their inspiration from research that was done on chimpanzees at a physiology lab in Yale. There was a great physiologist named John Fulton who had performed a number -- at Yale, he ran the Department of Physiology at Yale, and he had performed, partnership with a colleague, a number of experiments on these two chimpanzees named Becky and Lucy. And he had basically obliterated their frontal lobes, and he would run experiments with them before and after obliterating their frontal lobes, and he found that after the operations, the monkeys, or the chimpanzees I should say, were less capable of actually performing those experiments but that they performed them with less experimental neurosis, he called it, meaning that they wouldn't have tantrums, they wouldn't get upset when they couldn't, you know, perform the task.

DITTRICHAnd so that idea, well, if we're removing the neurosis of chimpanzees, maybe we'll do the same thing by performing this same type of operation on human beings. And so it was directly translated to human beings. And then there was this -- so the lobotomy was inspired by monkey research, or by chimp research in this case, and then this -- there was this weird, you know, murky relationship between animal experimentation and human experimentation where suddenly people who had been trying to understand brain function through the lesioning of animal brains suddenly realized that there was this opportunity to try to understand some of that -- you know, to try to explore those same questions with a much more useful experimental animal, which is the human being.

REHMWere there any oversights at the time?

DITTRICHVery limited. I mean, the notions -- you know, sort of our modern concept of informed consent really didn't exist at the time. And the patients that they were performing these operations on were basically as vulnerable as you can imagine any kind of group to be. I found this letter in the Yale archives, actually a letter written by John Fulton, the man who was sort of the intellectual godfather of the lobotomy. He was writing to a colleague of his, encouraging him to go spend a year with my grandfather exploring the lobotomies that my grandfather was doing, sort of studying the patients.

DITTRICHAnd he wrote to him, saying that, you know, Bill Scoville has just been given by the superintendent of this one particular asylum, the superintendent of this asylum has given Bill Scoville unlimited access to his psychiatric material.

REHMOh, dear God.

DITTRICHAnd I had to read it twice to understand what he meant by psychiatric material, which means, you know, he was literally given, you know, free rein to do what he wanted.

REHMI think the most prominent case of lobotomy that most of us know about is that of Rosemary Kennedy, and to this day there are questions about why her father, Joseph Kennedy, wanted her to have a lobotomy.

DITTRICHAnd those are very important questions, and one of the things you find when you look into the history of the lobotomy is that, well certainly in my grandfather's case, as in the case of most lobotomists, most of people he was operating on were women. And there is a sort of chilling overlap between the aftereffects of the lobotomy, being passivity, tractability, you know, and the sort of ideal feminine characteristics held by, you know -- the characteristics that men held to be the ideal sort of feminine characteristics of that era.

DITTRICHIn a certain sense you could say that a lobotomized woman might be viewed to be just sort of a better wife, more passive, more agreeable.

REHMOh dear God.

DITTRICHMore docile.

DITTRICHI mean that's -- whoa. There persists a rumor that Joseph Kennedy wanted Rosemary Kennedy lobotomized because she was too sexually active, and he wanted her to stop.

DITTRICHRight, and I think that that -- you know, that could very well be the case. I think -- and you look -- you look at what people were lobotomized for. In some cases it was for severe mental illness. In other cases it was for hyperactivity, for, you know, women who liked other women, for, you know, all sorts of, you know, just people prone to tantrums or, you know, there was certainly at place -- at play often, but there was also a lot of people who were lobotomized who we wouldn't consider to be greatly mentally ill.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." I want to take a caller. From Houston, Texas, Millie, you're on the air.

MILLIEGood morning, Diane.

REHMHi.

MILLIEI just wanted to say I'm retired from clinical neuropsychology, and I remember very, very clearly the first time I heard of HM when I was an undergraduate at Berkeley nearly 30 years ago. And I just wanted to say that although what happened to him was tragic, those of us who work in the cognitive neurosciences hold a tremendous affection for him because he taught us so much about memory and the structure of memory.

MILLIEOne of the most important things he taught us is that memory isn't a unitary process and gave birth to the idea of procedural memory. When HM was given a task such as mirror drawing, he continued to improve every time they gave him the task. Even though he did not remember ever having done the task, he improved every time you gave it to him.

REHMThat's interesting.

MILLIEAnd that taught us that learning and memory isn't a unitary process and that there are aspects of learning and memory that take place outside of consciousness, which is a really -- led to all sorts of different directions, into research into cognition other than memory. And I'd also like to say that because of the physics of traumatic brain injury in automobile accidents, the same structures that HM lost are often damaged in people who survive traumatic brain injury and that those things that were learned by HM have contributed so much to the rehabilitation and understanding of what people who've had traumatic brain injuries resulting from car accidents and the understanding that their families have, their situation and things like that.

REHMIndeed.

MILLIESo I don't know what your grandfather was thinking, and it was so long ago. I believe that he truly believed that he was going to helping HM. And although you wouldn't wish what happened to HM on anybody...

REHMExactly. You know, when you think of the absolute dictum to do no harm that doctors say they're going to practice, you suggest in the book that perhaps he should never have done this operation in the first place.

DITTRICHRight, I think that most neurosurgeons looking back on the operation would find it very hard to justify, even at the time, performing the operation that he performed. He had no clear -- he had no clear evidence for an epileptic focus. So -- and he instead of -- he really had no evidence that would lead him at that point to even remove one -- remove the medial temporal lobes from one hemisphere in the brain. And instead he went in and removed both.

DITTRICHSo yeah, it's hard to justify. On the other hand, it led, as the caller mentioned, to all sorts of amazing discoveries.

REHMLuke Dittrich. The book we're talking about is titled "Patient H.M." If you'd like to join us, 800-433-8850. Stay with us.

REHMWelcome back. If you've just joined us, Luke Dittrich is with me. His new book about patient HM involves his grandfather, who was a neurosurgeon, a very prominent neurosurgeon. HM was a young man who, at age 8 or 9, suffered after being struck by a bicycle, slammed his head, and began suffering increasingly frequent epileptic seizures. Luke's grandfather performed an operation on his brain. The question is did Dr. Scoville, your grandfather, actually expect that the operation would cure HM's seizures?

DITTRICHI think he hoped that it would. I do believe that ultimately he wanted to help Henry.

REHMDid he stay in touch with Henry after the operation?

DITTRICHHe didn't -- he did not stay in close touch, no. They fell out of touch.

REHMIn touch at all?

DITTRICHWell, there were follow-up appointments. He did, you know, he stayed in sort of minimal touch with him, I would say. But ultimately they didn't have very close contact with one another.

REHMI wonder if he talked with your parents about the operation and to what extent he may have felt any remorse.

DITTRICHWell, this is one of those things where although it was a story that I was always aware of, it was also a story that, in the family at least, wasn't talked about too much. I do think that in a sense -- and this something that I've dealt with and grappled with as I've been working on this book, is that he -- this is considered to be kind of his biggest mistake, in some senses.

DITTRICHAnd I think that the idea of my focusing on his biggest mistake when he had this, you know, huge career, when he saved the lives of hundreds and hundreds of people, and, you know, I'm somebody who has saved zero lives. And I also try to keep that in mind. So this was a situation where, you know, I'm focusing on an aspect of his career that my family would in some cases prefer that I not focus on.

DITTRICHWhat I discovered, though, was that it wasn't -- it certainly wasn't his only -- whether you want to call it mistake or not. That he had actually been participating in this long, long sort of campaign of what's hard not to call human experimentation. That, you know, there was, you know, a multiple series of experimental brain operations that he was performing in the back wards often of asylums in the years leading up to the operation he performed on Henry.

REHMLet's go to Mohammad in Indianapolis. You're on the air.

MOHAMMADYes. I was wondering, considering the syphilis study with the African-American people back then and how they were sort of guinea pigs and those experiments -- that experiment, as well as others. I was wondering to what degree did your grandfather use as patients or experimental people some of the African-American people.

DITTRICHThat's a very good question. I don't know the specifics of sort of the racial makeup of my grandfather's patients. I don't believe that they were, though, in any way predominately African-America. I do know though that the most prolific lobotomist of all time, a man named Walter Freeman, did perform down in Mississippi specifically. Performed a great number of lobotomies on African-American patients down there.

MOHAMMADThank you very much. I appreciate that.

REHMAll right. Thanks for calling. How much of an outlier do you think your grandfather was?

DITTRICHI think it's actually important to note that he was not really an outlier. That he, you know, that the lobotomy, that psychosurgery as a whole was not some fringe, you know, radical, you know, quack-dominated thing. It was the mainstream. And it was viewed as, you know, the best hope for the treatment of mental illness for a substantial period of time. And in fact it wasn't until the early 1950s that it sort of fell out of favor.

DITTRICHSo in that sense he wasn't an outlier. He was an outlier in that remained passionate about psychosurgery and the lobotomy long after it had fallen out of favor in the mainstream. And I think part of that, and one of the things that I kind of dug up in the book, and some of the hardest stuff to report on, part of that is that my own grandmother, his wife, was mentally ill. And she was institutionalized in at least one of the asylums that he himself was performing these operations in.

DITTRICHAnd he -- there's evidence I found in letters that he was so passionate about psychosurgery and the lobotomy in part because he was on this sort of relentless quest to discover a surgical fix for mental illness because he wanted to basically be able to fix his own wife.

REHMDid he participate in performing a lobotomy on your grandmother?

DITTRICHThat's a very difficult question to answer. I was told -- and this was probably the most sort of shocking moment during the reporting in my book. I was told by a colleague of his, that was in a position to know, that yes, he had done so.

REHMLuke, you make me cry. And I'm sure that revelation hit you pretty hard.

DITTRICHIt shook me to the core, I guess. You know, it's one of those things where -- this is a book about memory, right? And in a certain sense it made -- it sort of shifted my own memories, you know, of my childhood, of my grandmother, of their relationship. I, you know, I would think back to Thanksgiving dinners, sitting around a table and they're both there. And, you know, thinking about all the things that are not said and not known and all the kind of, you know, the secrets lurking beneath the surface.

REHMDid your mother and father talk with you, before you wrote this book, about -- whose father and mother…

DITTRICHThis is my mother's father. My maternal grandfather.

REHMAll right.

DITTRICHYeah, and she, you know, this is -- I've done a lot of investigative journalism in the past. And so I'm used to, in a certain sense, you know, writing stories that ultimately sometimes cause some pain to other people.

REHMAnd have shocking ramifications.

DITTRICHRight. And -- but usually when I'm doing a piece of investigative journalism I, you know, I do the reporting and then I sort of lob it like a, you know, like a grenade into somebody else's life. This is the first time when the story hits so close to home. And that some of the people that I'm, you know, causing pain to, are the people I care most deeply about, my mother included.

DITTRICHAnd I had to grapple with that. And I ultimately had to decide that, you know, the story was worth telling, despite the pain it might cause. And I don't know what that says about me, but that was the decision I made.

REHMAre your parents still living?

DITTRICHYes. They are.

REHMBoth of them?

DITTRICHYes, they're both still living.

REHMAnd I'm sure your mother has seen the book.

DITTRICHYes.

REHMHas she read it?

DITTRICHShe has read the book. And…

REHMWhat was her reaction?

DITTRICHYou know, my -- and I adore my mother and she's a fantastic mom. And as she's, you know, my biggest fan and my biggest support. But I'll -- I -- the first time I -- right after I got the book deal I called her up to let her know that I had just gotten my first book deal. And her first words were, oh, no. Because, you know, as much as she, you know, loves and supports me, she also knew that I was going to be treading on some dark aspects of the family history.

REHMWhen you think about -- when I think about frontal lobotomies, I think about "One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest," and Jack Nicholson at the horrific ending of that film. And I wonder if you saw your grandmother after she had surgery.

DITTRICHWell, again, and I want to just make clear that although I was told that he had performed this, I don't know for sure.

REHMYeah.

DITTRICHBut I knew my grandmother very well. She died when she was 101. And she, you know, she was a great grandma. I will say that the sort of -- the conception that most people have of the after effects of the lobotomy, the "One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest" sort of idea, doesn't hold true for a lot of the lobotomies that were performed. There were -- they became increasingly refined.

DITTRICHAnd my grandfather actually, his whole passion was to find a way to sort of fine tune the lobotomy to make it less -- he called it blunting. To have less of an after effect on the personality, to more precisely target just the mental illness so that people who received his lobotomies could seem much more normal and less, you know, zombified.

REHMAll right. Let's go to Ellen in Rochester, N.Y. You're on the air.

ELLENHi. I just tuned into this program. And I immediately perked up because this brought me back 60 years to my own father who was a neurosurgeon, trained by Fulton at Yale, and who performed lobotomies, and performed on a house robber that was in jail and volunteered for this surgery. My father wrote a book about this. He appeared on "The Today Show" with Dave Garroway, if you can remember that far back.

ELLENAnd he was (unintelligible) of this kind of surgery. And I remember him talking about this quite openly and positively at dinner. And the best part was that the brain of this person who had had the lobotomy, after he died, was given to my father who wanted to study its biology to see whether or not this brain was different. And the brain hung out in my father's study at our house.

REHMDear God.

DITTRICHThat's amazing.

ELLENSo I became a local celebrity on the street, you know, all the kids wanted to come in and see the brain.

REHMYeah, I can imagine.

DITTRICHThat is a fascinating story. Wow. Wow. And, yeah, it reminds me, you know, one of the things I explore in the book is Henry's brain and what happened to Henry's brain after Henry died. And ultimately there was a big sort of custody war over the possession of Henry's brain. Because, again, people wanted…

REHMBetween who and whom?

DITTRICHWell, between -- ultimately between MIT and Mass General Hospital and UCSD. It had -- after Henry died it was -- his brain was removed and then it was ultimately escorted to the University of California San Diego, where a neuroanatomist worked with it for several years, sliced it into 2,401 pieces, sort of digitized it, created a 3D model of it, and then ultimately it was taken away from UCSD.

REHMAnd given to?

DITTRICHAnd given to the -- a scientist that MIT had chosen at University of California Davis, which is where the brain now resides. But it became this sort of secret, you know, almost legal battle over the possession of his brain.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Here's an email from James, who says, "Wouldn't simple experiments on mice or monkeys before HM's surgery have demonstrated that, number one, the ability to form new memories would be lost and two, the epilepsy would persist?"

DITTRICHThat's a great question. I think the difficulty and the reason why animal experiments wouldn't have necessarily indicated -- certainly in terms of the memory issues -- is that animals, you know, the problem with animals is that they can't talk. And there's a line that I actually open with the book with by another neurosurgeon who also sort of straddled that practice/research divide like my grandfather, a man named Paul Bucy, who wrote, "A man is certainly no poorer as an experimental animal merely because he can talk."

DITTRICHAnd, you know, there's -- and patient HM also, in terms of the reason he became some important, despite the fact that my grandfather had actually been performing on humans for years prior to his operation on HM, he had been performing some nearly identical operations on asylum patients. They were so deeply disturbed that it was difficult to glean useful information from them post-operatively.

DITTRICHWhat made Henry, in some senses, so valuable was that he was -- scientists call it pure. He was -- he didn't have other deficits. He, you know, cognitively he was okay. He didn't suffer from mental illness. And so they had a much clearer kind of, you know, picture of what happens when you remove these portions of the brain.

REHMSo, Luke, you have finished the research. You've written the book. It's now talked about. How has the process affected you?

DITTRICHWell, I think the -- it's still ongoing. I mean, I am still kind of grappling with some of the things I found out. I still have things I'm still curious about.

REHMSuch as?

DITTRICHWell, I, you know, the idea of, you know, whether or not he performed that operation on my grandmother. There are still, you know, there's -- it's -- some stories never end. And I think I'll still be, you know, grappling with patient HM's story and some of its kind of ramifications for a long, long time. And -- but, yeah, I mean, it's -- I've been working on this for a long time. And it's gonna be -- I'm, you know, I'm happy to have it sort of out in the world now. I mean, I think one of the things I set out to accomplish, patient HM has been written about many, many times.

DITTRICHYou know, there -- I'm certainly not the first person to write about patient HM. But the story of patient HM, up until now, has been dominated by the -- in large part by the researchers, the scientists who had an interest in telling his story in a particular way. And HM himself couldn't tell his own story. And so I wanted -- one of the things I wanted to accomplish was to sort of take his story back.

REHMI think you've done it well.

DITTRICHThank you.

REHMThank you.

DITTRICHAnd thanks for having me.

REHMLuke Dittrich, the book is titled, "Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets." Thanks for being here, Luke.

DITTRICHThank you for having me.

REHMAnd thanks all for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.