Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

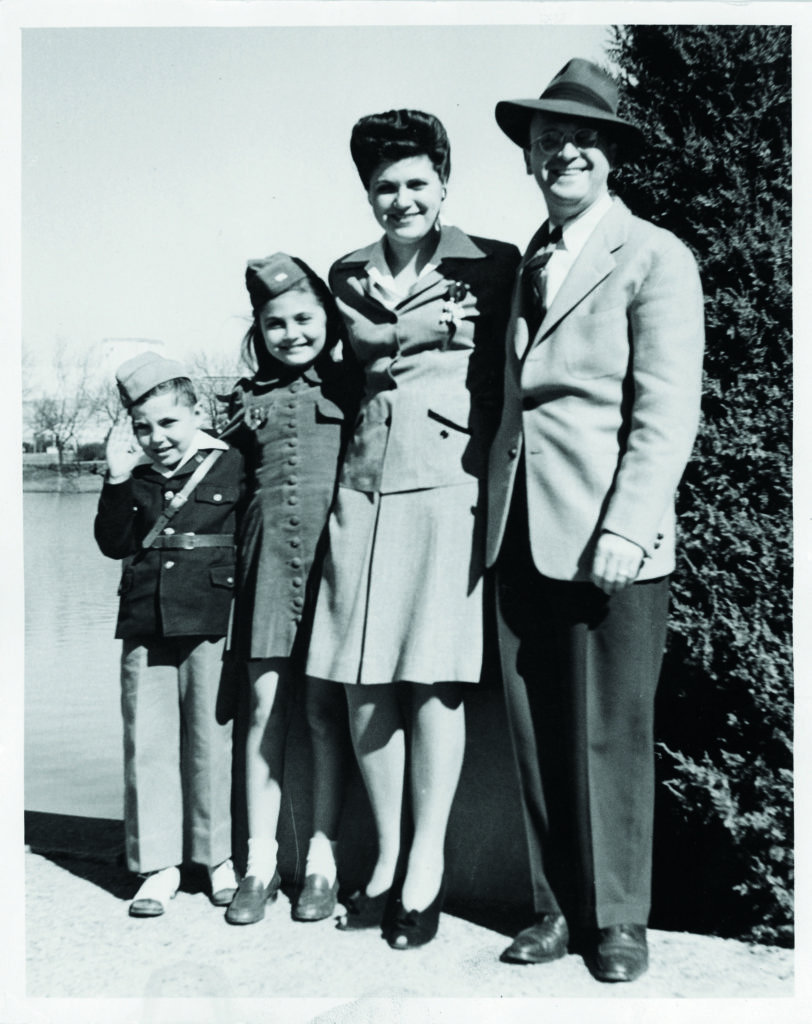

Abraham and Lillian Zapruder with the children, Myrna and Henry, at Fair Park in Dallas, Texas, 1942.

Fifty-three years ago, Abraham Zapruder stepped out of his office in Dallas, video camera in hand, to catch a glimpse of President John F. Kennedy. Zapruder was a Jewish immigrant who had come from nothing but was living the American dream with his own dress-making business, and a middle class family. He was not a likely candidate to change the course of history but when he captured the assassination of JFK on film, his name became inseparable from the event – and the video at the center of controversy and conspiracy that would continue to this day. In a new memoir, his granddaughter, Alexandra Zapruder, sets out to better understand the film and her family’s relationship with it. She is the author of the new book “Twenty-Six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film.”

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. On November 22nd, 1963, Abraham Zapruder left his office in Dallas with his Bell and Howell movie camera, excited to capture the motorcade of President John F. Kennedy. He ended up filming the assassination of JFK, 26 seconds of film that would forever change life for his family. In a new book, Alexandra Zapruder, the granddaughter of Abraham, explores the complicated history of the film.

MS. DIANE REHMHer book is title, "Twenty-six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film." Alexandra Zapruder joins us from KERA in Dallas. And of course, we'll be taking your calls, comments, questions throughout the hour, 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or Twitter. Alexandra, it's good to see you.

MS. ALEXANDRA ZAPRUDERThank you so much. I'm so glad to be here.

REHMAlexandra, tell us why you felt it so important to write this book.

ZAPRUDERSo you know, it turns out that the story of the Zapruder film is a completely fascinating one, but this isn't really something that I knew when I was growing up. You know, I grew up in family where we really didn't talk very much about the film. And I think it had a lot to do with the very strong sense of the importance of discretion around it, the importance of respecting the Kennedy family, honoring my grandfather's wishes never to exploit the film.

ZAPRUDERAnd so there was a kind of reserve around it and we just didn't -- it wasn't something that I knew very much about. And then, after my father died rather young, I found myself feeling that I should take responsibility for some of the material records in our family, the papers, the -- an opportunity, perhaps, to interview people who were close to our family who knew the history of the film because I hadn't been able to interview my father before he died.

ZAPRUDERAnd as I gathered the papers and as I began to learn about this history for the first time, I was stunned and amazed by not only how extraordinary the story is of the film and how much our family's story was intertwined with it, but the way in which the threads of the story connect to some of the most important questions of Americans today.

REHMAnd, in fact, your grandfather died either shortly after you were born -- is that correct?

ZAPRUDERThat's right. He died in 1970 so my twin brother and I were just about 10 months old when he died. And he did see us once in the hospital here in Dallas, but, of course, we never knew him.

REHMSo you never knew him, but your father had all this information. He never talked about it.

ZAPRUDERHe talked a little about it. You know, at times, when the film was very much in the public eye when there were events going on that caused there to be newspaper articles and that kind of thing, it would come up. But, you know, the film was very painful for my grandfather and it was very painful for my dad as well. And so it just wasn't a topic that they wanted to talk about, I think. It wasn't so much that there was any kind of taboo or that it was, you know, that I wouldn't have gotten my questions answered if I had thought to ask them, but it was just in the periphery of our lives.

ZAPRUDERI knew it was there. I knew about the film. I knew that it was the same as my name, but I didn't -- I was too busy just living my life.

REHMLiving, sure.

ZAPRUDERWe were all too busy living our lives the way that people do, yeah.

REHMYou know, it's interesting because every year, on the anniversary, almost the Zapruder film is shown and surely as you were growing up, you must have seen it and I wondered whether that had created questions in your mind that you then put to your father while he was alive.

ZAPRUDERYeah. It's interesting. I mean, I actually didn't see it until I was in high school, you know. It wasn't -- I mean, part of this is about technology and this is, in fact, a story about changing technologies because, you know, I grew up in the 1970s and '80s so it wasn't as if, you know, you could turn on the computer and see the Zapruder film on YouTube. If you wanted to see it, you had to try.

ZAPRUDERAnd no one in my family would've put it in front of me willingly because it's so violent and so gruesome and so terrible. So I didn't see it until I was in an American history class in my high school when I was 15 or thereabouts. And so for that reason, I think, again, I didn't really have questions about it. When I finally saw it for the first time, of course, I was horrified.

REHMTell me your reaction a little bit more than being horrified that first time you saw it.

ZAPRUDERYou know, I wish I could say that I remember it better. I think what I felt was a kind of -- we inherited a way of thinking about the film, let me put it that way. And what I mean by that is that we were never able to forget that this was a record, first and foremost, of another family's tragedy, of the death of a man. Not just the president and how it was for nation, but of an individual, the man, a father, a husband.

ZAPRUDERAnd so I think that's what I saw. You know, I didn't -- I never associated the film with my grandfather. I associated it with President Kennedy and his widow and, you know, that is, after all, what the film is about. It's not really -- there is a story about us, but the film is not about us in that way.

REHMIt's really amazing to see it even on the cover of your book. I have to tell you that at the time, my husband was working in the White House and when President Kennedy's body came back, we were asked to come down to view it, along with other members of the staff. So I saw, I saw everything from beginning to end and it's really horrifying for me to remember those days. And I can only imagine what it must be like for you now to have gone through all these papers, to have recalled what was happening in your own family and the feelings that must have been present.

ZAPRUDERYou know, it's so interesting because I think what you describe is so much the experience of my parents and my aunt and uncle and my grandfather and grandmother, you know, the people who were Kennedy people. You know, and I always think about -- I described this in the book that, you know, my aunt -- my Aunt Myrna was with her friend Ruth at Love Field when President and Mrs. Kennedy arrived in the morning to greet them. My aunt had volunteered in the Kennedy campaign.

ZAPRUDERMy Uncle Myron was in his office at the Praetorian Building on Main Street watching the motorcade go by. My parents had just moved to Washington D.C. because my father had gotten a job in the Kennedy administration working for Bobby Kennedy and he had written, in 1962, one of the incredible things that I found in the course of the research, was this absolutely beautiful letter from an idealistic, young Henry Zapruder, my father, at the age of, you know, 24 pleading for a job in the administration saying, I want to come work for the new frontier.

ZAPRUDERAnd so -- and then, after when the president's body was lying in State at the Capitol building, my parents and my Uncle Joe came and stood in line all night to wait for their turn to file past the president's body. So the Zapruders were Kennedy people in the deepest sense of the word and my grandfather loved President Kennedy. He said so many times after the assassination how painful it was for him to be associated with his death when it was his life that he so admired. And my father felt the same way.

REHMWhat happened after your grandfather took those films?

ZAPRUDERSo he was on the plaza, on Dealey Plaza. He was, I'm told, distraught. He was screaming, they've killed him. He was hysterical. You know, he saw through the zoom lens so there was no question in his mind that the president was dead, although the people around him, of course, didn't know that yet. And he was approached by Harry McCormick, who was a Dallas Morning News reporter, who saw him with the camera and asked him if he had something filmed of the event.

ZAPRUDERAnd my grandfather said, I need to be in -- I need to see the federal authorities. I need to get this to the federal authorities. That was instantly his primary focus. And so Harry McCormick went to locate Forrest Sorrels who was the head of the Secret Service in Dallas and my grandfather went back to his office and called my father. And my father recalled later this conversation that they had, that my grandfather was crying. He was saying, the president is dead. There is no way that he could've survived.

ZAPRUDERI saw everything. And saying over and over and over again that he couldn't believe that this happened in America. You know, he was a Russian immigrant. He had come to this country in 1920 as a 15-year-old boy, fleeing oppression in Czarist Russia as a Jewish immigrant and poverty-stricken and, you know, so much trauma there. And here was America where, you know, this country that had -- where he had sought refuge and that had given him a home and where he had found success.

ZAPRUDERAnd so America represented progress and democracy and the future. And John F. Kennedy represented that most of all. And so for my grandfather, he kept saying, you know, they shot him down like a dog on the street and this is, like, what would happen in Russia. So that phone call happened. My father, I think, encouraged him to get the hands into the federal authorities and then began this very long, involved process of getting the film developed.

REHMAlexandra Zapruder, her new book, a personal history of the Zapruder film, is titled "Twenty-six Seconds." And if you'd like to join us, 800-433-8850. Send your email to drshow@wamu.org.

REHMWelcome back. Alexandra Zapruder is my guest. She joins us from KERA in Dallas, Texas. Interesting that you are in Dallas, Alexandra. And her new book is titled "Twenty-Six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film." Just before the break, we were talking about exactly what happened after the assassination occurred, and your grandfather kept saying, I need to speak with a federal authority. Here is a recording that we have, an interview following the assassination with WFAA Television in Dallas. Your grandfather had come to the TV studio with the Secret Service to try and get the film developed for the federal government. And it turned out to be difficult.

UNIDENTIFIED MALEA gentleman just walked in our studio that I am meeting for the first time as well as you. This is WFAA TV in Dallas, Texas. May I have your name please, sir?

MR. ABRAHAM ZAPRUDERMy name is Abraham Zapruder.

MALEMr. Zapuda?

ZAPRUDERZapruder, yes, sir.

MALEZapruder. And would you tell us your story please, sir?

ZAPRUDERI got out and about a half hour earlier and get us a good shot to shoot some pictures. And I found a spot, one of these concrete blocks they have down near the park, near the underpass. And I got on top there. There was another girl from my office, she was right behind me. And as I was shooting, as the president was coming down from Houston Street making his turn, it was about a half way down there, I heard a shot. And he slumped to the side like this. Then I heard another shot or two. I couldn't say whether it was one or two. And I saw his head practically open up, all blood and everything. And I kept on shooting.

REHMPretty grim memories, Alexandra.

ZAPRUDERYes. And, you know, whenever I heard that piece of tape, I think, you know, I heard his grief. You know, I hear the sound of his voice and his struggle to maintain his composure in that -- in the aftermath of this terrible shock. You know, and my grandfather -- I should just say -- my grandfather was a very avid and devoted home-movie maker. He'd been taking home movies since the '30s, since 1934. And we -- I wrote this in the book -- we have these hours and hours of very unexceptional home movies, like everybody else does of, you know, my aunt and my dad growing up. And they're so lovely and wonderful and they capture this time that is gone. But it was a tremendous joy for him. He loved his camera. And I think that, you know, this was just such a, you know, such a shock and such a painful turn of events for him.

REHMWas he afraid that the whole world might see that film?

ZAPRUDERYes. I think that was his immediate concern. I mean, I think that's why he wanted to get it into the hands of the federal authorities of course feeling that, you know, it was likely to be useful as a piece of evidence. But he was very -- immediately consumed with the worry that the film would be sensationalized or exploited, that it would be splashed all over the newspapers. And, in fact, he was from, you know, almost immediately approached by members of the media -- first by Harry McCormick and then Darwin Payne, who was working for the Dallas Times Herald, and then over the course of the day by other reporters, and then the next day thronged by reporters who wanted to purchase it.

ZAPRUDERAnd, you know, some were kind and respectful and some were very aggressive and pushy. But I think it was, you know, a real worry for him about how to navigate that situation without doing damage -- further damage to the Kennedy family.

REHMBut he finally agrees to sell it to LIFE Magazine. Tell me why.

ZAPRUDERWell, the main reason -- there are two reasons. One reason is that LIFE Magazine, of course, was in those days incredibly well loved.

REHMHuge. Yes.

ZAPRUDERHuge. Huge. Well loved, very well respected. It was, you know, the primary, you know, it was a magazine that everybody read and it, you know, it had pictured so many times the Kennedy family. There was a special relationship there. And so that was an obvious choice in a certain way for strong pictures like this, powerful pictures.

ZAPRUDERBut the real reason is Richard Stalley, who was the young LIFE reporter, LA bureau chief, who came to Dallas that day, on the 22nd, and reached my grandfather that evening at home. And Richard Stalley was very much a gentleman. He really separated himself from the pack of other reporters who were clamoring for the film. He treated my grandfather with a lot of respect and decency. And he promised that LIFE would treat the film with dignity and with restraint, which was my grandfather's primary concern. So the two of them really made, in addition to an actual agreement to sell the film, a gentlemen's agreement that the film would be treated, you know, in accordance with my grandfather's wishes.

ZAPRUDERAnd that is -- was something that LIFE honored for the full 12 years that they owned the film and under tremendous fire at some times during that period.

REHMWhat did that mean, to treat the film with honor?

ZAPRUDERRight. That is a good question. I think it meant not to sensationalize it. And, in particular, it meant not to overexpose or show the most graphic frames of the film. You know, C.D. Jackson, who was the publisher of LIFE, was very concerned that the American people not see these images. And one of the things about writing this book and about this story is that it becomes impossible to forget the particulars of the time in which these events occurred. You know, the very idea that a publisher would want to protect the American people from violent images, rather than rushing to show them violent images, is in itself a commentary on the time.

ZAPRUDERSo there was this sense of, you know, respect for the Kennedy family, respect for their privacy, as sense that, you know, this would sort of trip a wire in a way or maybe un, you know, leash the floodgates or however you say it. That, you know, this would begin this kind of flood of violent images and that LIFE couldn't be responsible for being the first to publish something like that.

REHMAnd, yet, because the films are such an accurate portrayal of exactly what happened, they're used and seen over and over and over again, talking about from what direction the first bullet hit, then the second bullet, the one that took -- aimed at Governor Connally. I mean, it became such a part of American history and the investigation as to who killed JFK.

ZAPRUDERAbsolutely. I mean, it was of course used in the Warren Commission and it was the centerpiece of other investigations over the years -- both government investigations and official ones and those within the assassination research community, people who believed that it was the unequivocal evidence that a conspiracy had taken place. And one of the things about the film that, I think, keeps it so much in the public -- in public life and mean -- is that it doesn't really bring about a consensus about what happened to the president. Everyone who sees it, sees it through the lens of their own beliefs, their own understanding, their own history, their own background. And people see the same piece of film very differently.

ZAPRUDERAnd one of the things that I think about so much when I think about the film is that, you know, the film never changes. The film is always the same every single time. But everything else changes. The perspective of the person looking at it, the times change, the technology changes, the culture changes, everything else around it has changed again and again and again and, therefore, it is read in different ways over time.

REHMAlexandra, has the public seen every single frame of that film?

ZAPRUDERThe public has seen every single existing frame. The film was -- the original film -- actually, yes, the public has seen every frame. The film -- the original film was damaged at LIFE Magazine the very weekend of the assassination, and a small number...

REHMHow so? How so?

ZAPRUDERSomehow during the duplication process, to put it in the pages of the magazine, a technician damaged some frames. I don't know exactly how that happened. It was...

REHMAnd, Alexandra, that, in itself...

ZAPRUDERYeah.

REHM...would create questions in the minds of people.

ZAPRUDERAbsolutely. Although, it's important to know that there had already been three duplicates made of the film prior to that time. So those frames were not lost. The frames existed on the immediate -- what we call the first-day copies. So -- but what LIFE Magazine did was that they didn't make that information public at the time. It took several years before they came out with a statement about it. In this climate of suspicion and growing suspicions about whether or not what happened to the president was being accurate reported by either the media or the federal government, certainly something like that could take on a life of its own.

ZAPRUDERAnd that was only one example of the ways in which those kinds of controversies and those kinds of speculations about conspiracy grew up out of the LIFE Magazine years. And, again, one of the things that I think about a great deal is this idea of unintended consequences, which is the story is a book of unintended consequences -- people making decisions in real time as best they can, with the knowledge that they have and then what results is completely unexpected.

ZAPRUDERAnd a great example of that is, that here was LIFE Magazine trying to protect the American people and respect the Kennedys by not showing the film to the American people. And yet, in many ways, that fed the sense that something was being kept from the American people and caused, you know, bootlegs to begin to circulate and all kinds of frenzy around the film through the 1960s and the early '70s.

REHMTell me what happened once your grandfather had made the deal with LIFE Magazine. There was a certain amount, perhaps a great deal of criticism of him.

ZAPRUDERWell, it's interesting. He -- there wasn't -- he was afraid of criticism. So he sold the film to LIFE Magazine for $150,000, which of course in 1963 was a large sum of money. But he was very troubled by the moral implications -- which is something that our family has contended with for all of these years -- the moral implications of profiting in any way from this national tragedy. And so he -- one of the things that -- one way in which he responded to that was to entrust it LIFE. But another thing that he did was to donate the first installment of the money that he got from LIFE Magazine, $25,000, to the widow of J.D. Tippit, the police officer who had been killed in the movie theater by Oswald.

ZAPRUDERAnd I think my grandfather felt, you know, that he was caught between, you know, this sort of sense of responsibility for the public good and needing to entrust the film to a place that, you know, that would care for it in the right kind of way and the financial gain that it represented. And don't forget, you know, he had grown up brutally poor in Russia. He was a Russian immigrant. And, you know, I think anyone can understand how hard it would have been to walk away from that money, even though it brought with it a great deal of uncertainty and moral doubt.

REHMConsidering the amount of research you've done, how much of an outcry was there that he had taken that money from LIFE?

ZAPRUDERWell, what's so interesting is that there wasn't an outcry about that. What ended up happening is that the news story about him donating this $25,000 was picked up by the national and international media. And so what ended up happening instead was that he was flooded with letters, these beautiful letters from people thanking him for this gesture. And some of them are under the impression -- some of the people were under the impression that he had donated all the money that he got from LIFE Magazine and some weren't.

ZAPRUDERBut, you know, the end result was really that he was lauded for having done something kind and generous with this money in the aftermath. You know, people felt that it sort of was a gesture that restored their faith in people's decency. The actual internal questions for him remained. But that was the public reaction.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Here's an email from Alan, who says -- I'm sorry, it's from Aaron. He says, I believe your grandfather recorded the most civilian -- the most famous civilian video in history. I was wondering if your grandfather was ever offered opportunities to appear on talk shows throughout the years, for example, Johnny Carson, Merv Griffin Show, anything like that?

ZAPRUDERHe would not have done that. He died in 1970 as it happens. So he died only seven years after the assassination. But he really shunned the media spotlight in general. Again, this was very traumatic for him, extremely traumatic. And although he gave a few interviews over the years, he certainly would not have done anything like that. And, in fact, in the years that my father was responsible for the film, he avoided any type of, you know, sort of attracting attention through the media as much as he could as well. So I'm definitely breaking with tradition by writing this book, I would say.

REHMI wonder, you talk about his feelings of trauma after the assassination and, of course, going through all this with the film. Did your father ever relate to you how your grandfather expressed that feeling of trauma?

ZAPRUDERNot really. I mean, again, it was such a different time, you know? He was a 58-year-old Russian immigrant to this country. You know, he wasn't someone who -- when this happened, he wasn't someone who would have sought counseling or therapy, although it certainly would have been good for him, given what he had witnessed. But I think he, you know, sort of dealt with it in his own way, privately. And there wasn't a lot of talk about it, even inside the family. And, in fact, my aunt has said to me many times that she regrets, you know, in some ways that they didn't talk more about it.

ZAPRUDERBut, again, you know, I don't think anybody could have foreseen in that moment the life that the film was going to have and the historical significance that it was going to have. And so it wasn't as if they were recording memories for posterity. It just didn't -- I don't think it seemed that way in the time.

REHMWas your grandmother alive at the time?

ZAPRUDERYes. My grandmother was alive. And my grandmother died in, I believe, it was 1993. And she and I were very close. And she was a wonderful, incredible, vibrant, exuberant, vivacious person. Very -- quite different from my grandfather, I think, who was more reserved. Very -- he was very funny and eccentric and talented. But they were very different. But, again, she and I didn't talk about it either.

REHMYou didn't?

ZAPRUDERNot really. I mean, you know, my grandmother was too busy trying to feed us rugelach and give us, you know, I don't know, lemon squares or -- you know what I mean? We were -- we're just a family -- like, we're just a normal family. And so we didn't really talk about it. Although I will say that she did have more of a sense of wanting to preserve my grandfather's legacy, I think, than many others in the family. And one of the things that she did, for which I am so grateful for this book, is that she preserved all the letters that he got and all the correspondence that he got regarding the $25,000 that he donated. So I had that to use.

REHMAlexandra Zapruder, her book is titled, "Twenty-Six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film." Short break here and your calls when we come back. Stay with us.

REHMWelcome back. Alexandra Zapruder has told the fascinating story of the film taken by his grandfather, who indeed had his own camera with him on the day President John F. Kennedy was shot and took what has become known as the Zapruder film. Alexandra's book is titled "Twenty-Six Seconds." It's probably something of a surprise that the first time the film aired on television is 1975 on "Geraldo." Tell us how that happened.

ZAPRUDERSo I mentioned earlier that, you know, there was quite -- quite a lot of activity among the assassination research community around the Zapruder film and wanting to get access to the film to be able to study it. And so there were bootlegs that were circulating over the years. Some of them -- one major source was Jim Garrison, who of course was the DA in New Orleans who brought about the -- who tried the Clay-Shaw trial, and that was one source.

ZAPRUDERThe film had been subpoenaed by Life magazine. It was entrusted to Mr. Garrison with the stipulation that it not be shared, and he promptly set about making as many copies as possible and distributing them as widely as he could. But another gentleman named Robert Groden was, you know, very -- had a lot of questions about the assassination, certainly a conspiracy theorist, and he obtained a copy of the film through channels that had to do with Life magazine, which was trying to make a 35-millimeter version of it.

ZAPRUDERAnd he set about making a highly stabilized and sort of zoomed-in version of the film that would be much easier to see, and it was Robert Groden who aired the film with Geraldo Rivera, a bootlegged, illegal copy of the film in 1975. And I always think about this. I spoke with Robert Groden, among many other people, for this book. And, you know, some people react to that by saying, you know, that must have -- your family must have been so angry, or that must have been so terrible.

ZAPRUDERBut, you know, from my perspective today, I think, you know, there was a certain inevitability to that. The film was not available to the American people, and times had changed. You know, the things that could be tolerated in 1963 or even 1965 simply could not be tolerated in 1975, post-Watergate, Vietnam War, you know, a growing mistrust with the government.

ZAPRUDERSo in a way, that feels like something that had to happen sooner or later, and this did -- Life magazine had already been considering giving the film back or trying to give the film to either a public institution or our family. But this did precipitate those events.

REHMAnd then they sell it back to your family for $1.

ZAPRUDERFor $1.

REHMAnd then your father is in charge of this whole mess.

ZAPRUDERAbsolutely, and my father inherited a tremendous responsibility because Life's choice to not allow the film to be seen -- it was published -- stills of it were printed, but to not allow other networks to share it or air it anything like that, meant that there was no policy at Life magazine for how to handle it, which put my father in the position of having to develop one because there were constant requests for use of the film, and there was always this challenge of how do we balance the public interest in the film and the public's need to see the film with our own family's values and our family's sense of what constitutes responsible use of the film. And that was not an easy thing to do.

REHMWell then -- pardon me -- comes Oliver Stone's movie about JFK. Did your father know who he was licensing it to, and what in the world was the result of that movie?

ZAPRUDERI don't think that our -- my father and his secretary Anita Dove, who helped him over many years working on this I don't think that they did know. I mean, I -- I don't know that I would go so far as to say that it was a deliberate trick, but I do think that it was not clear what this film was going to be and that it was a high-profile director like Oliver Stone.

ZAPRUDERSo when the film came out, when JFK came out, one of the things that followed from it, beyond, of course, reviving all the controversy around conspiracy theory, was that there was a move to make the records that belong to the -- that were in the federal government available to the American people.

ZAPRUDERAnd the film had been entrusted to the safekeeping of the National Archives in 1978 by our family. And so at that time there became immediately this question, is the film does the film belong to the federal government. Should the film -- should the federal government take possession of the film because it is in the holdings of the National Archive? So there then followed a five-year period in which our family negotiated with the Justice Department and the National Archives to try to determine were they going to take the film from our family essentially be eminent domain, the sort of same principle as when the government says we want to build a highway, and we have to tear down your house.

ZAPRUDERAnd the question of course that followed then was the question of just compensation, how much was the film worth.

REHMBut eventually the government sells it back to your family for $16 million.

ZAPRUDERWell actually they didn't sell it back. That $16 million was the just compensation for the Zapruder film. So the federal government took the film by an eminent domain taking, which is legal, the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution provides for that, but the question is, if the government takes your property, how much do they have to pay you for it.

REHMI see. I see.

ZAPRUDERAnd what was so fascinating, and I devoted the whole last chapter of the book to this, is how do you determine just compensation for the Zapruder film. How do you establish the value of something that is completely unique? And what that -- the way that it ended up happening was that an arbitration panel was established with three very eminent people who listened to the case on our side in the family and the government's side and attempted to come up with a number that would reflect the value.

ZAPRUDERBut what the hearing really became about was what is the Zapruder film. What does it mean? What does it mean in American life? What does it mean to the American people? What does it signify -- this and how does that -- how do those meanings get translated into a financial value, which I think is a sort of uniquely and interesting American question.

REHMThat money sort of goes head on against what your grandfather wanted.

ZAPRUDERWell I think it -- I don't know if I would say it that way. It's really -- it's interesting. I mean it's not that the thought has never crossed our minds, and I absolutely can understand why it would seem that way, but I think what our grandfather did is the same thing as what my father did. He took the money from Life magazine for the film, but he donated a portion of it to try to do good with it.

ZAPRUDERIn our case, we accepted -- we accepted just compensation for the film, which was our legal right to do, and we donated the copyright of the film, which the government didn't take, to the Sixth Floor Museum here in Dallas, which was a donation that of course is worth many millions of dollars. So it's always about finding a balance. It's always about how do you do the right thing for the public and honor the wishes of our grandfather but also, you know, tend to the wishes of -- attend to the wishes or the needs of our own family.

ZAPRUDERAnd I think my dad did the very best he could to try to strike that balance.

REHMAll right, let's open the phones first to Waterford, Virginia. Patty, you're on the air.

PATTYHi Diane. I'm going to miss you.

REHMThanks.

PATTYI worked on "JFK," and I was the location manager for Dealey Plaza. And, you know, having been a five-year-old kid when Kennedy was shot and then later on having seen the Zapruder film, it was such an emotionally charged job to be using the Zapruder film as our reference point for everything because as you know we duplicated everything in Dealey Plaza based on the Zapruder film research of who -- what extra was wearing, you know, what outfit in which place.

PATTYBut to work on it, it was really -- and I've worked on movies since 1980, but it was so painful because it actually tapped into an emotional part of my life because the Zapruder film was of course real, and what we were doing was not. And, you know, I was so happy that it was preserved, you know, and wherever anybody falls on, you know, what the point of view of the movie and the book is, which I ended up in my own place at the end of that.

PATTYBut it was really fascinating, blurring the lines of reality and fiction. So...

REHMYeah Patty, I'd be interested in your thoughts, having worked on that film, where you ended up. Did you find yourself agreeing with the conclusions of the Warren Commission, or were you persuaded by the film on which you were working?

PATTYOddly enough, you know, Diane, I expected to be persuaded by the film, and in the end I ended up feeling, more intuitively than anything else, a little bit influenced by the Warren Commission but just intuitively, that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. I didn't feel that it -- that all the things in Garrison's book really held together for me, having worked on it.

PATTYAnd what frightened me actually working on it was I was afraid that a copycat was going to happen while we were filming that because of how fanatical some of the Kennedy conspiracy theory and assassination people could be that we had everything exactly as it was, and we shut down the highway, and we controlled Dealey Plaza completely, and I was really frightened that something would happen that day when we were filming.

REHMYeah.

PATTYBut thankfully it didn't.

REHMWell I thank you for your recollections. How do you respond, Alexandra?

ZAPRUDERYou know, I think Oliver Stone's movie, I think of it more as an expression of, you know, the artistic intent of a very creative person. I don't -- of course I have a lot of, you know, questions about Jim Garrison and the validity of his methods and the, you know, appropriateness of his case. I mean, I -- so in that sense I think, you know, Oliver Stone's movie sort of revived and lent credence to something that I think was, I'm sorry to say, a travesty of justice.

ZAPRUDERBut on the other hand, he is an artist, and artists make things, and artists stir up controversy, and that is in some ways their role in our society. So, you know, for that I think, you know, one has to give him his due.

REHMAll right, and we have an email from Dallas in Pittsburgh, who says in 1973 or '74, I went to a church basement in Baltimore and saw a bootleg copy of the film frame by frame show by a conspiracy speaker. I did not sleep that night. I was in seventh grade in 1963. And you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show.

REHMAlexandra, I wonder if you would read for us from I think it's quite near the end of the book.

ZAPRUDERYes, this is the sort of the last paragraphs of the book, the epilogue to the book, in which I am doing my best to speak to the public legacy and the enduring legacy of the film and as I found it in the course of this work.

ZAPRUDERWhat is its public legacy? What is the compelling lure that makes the assassination researchers, the film, art and cultural historians, the writers and journalists, the academics and students and hobbyists and Kennedy buffs return to it as a touchstone time and again? I have come to think it is because the Zapruder film is in every way a conundrum. It contains its own irreconcilable contradictions. It is visual evidence that refuses to solve the mystery of who murdered the president, why and how. It is a single strip of film in which we all see different things.

ZAPRUDERIt shows the entire course of history changing under the influence of a single bullet. It is quite possibly the most important historical film ever made, and yet it is amateur home movie. It is six feet of eight-millimeter film on a plastic reel that turned out to be worth $16 million. It is the most private and the most public of records. It is gruesome and terrible, but we cannot stop looking at it.

ZAPRUDERBut more than that, the deepest, most compelling conundrum of the film is an existential one. It lies in the arc of the film itself, the fall from grace, the unforgiving inevitability of it. It is a sunny day, a handsome husband and his beautiful wife are riding down the street, smiling and waving, with their lives stretched out before them. And within less than half a minute, his head explodes, and he is dead.

ZAPRUDERHe is alive, and then he is dead. She is a wife, and then she is a widow. She is grace itself, and then she is sprawled across the back of the car. How can it be that our protections and illusions can be stripped from us so quickly? Most of us are able to live our days exactly because we are not confronted with this vulnerability, the inexplicable capriciousness of fate, the permanence of death.

ZAPRUDERAnd yet there is the Zapruder film. It exists, and we cannot turn away even though we fear it, and we avert our eyes, and we wish desperately that it would end differently every time. Maybe it is the same impulse that causes us to watch the Challenger explode in the bright blue Florida sky or the Twin Towers crash down into Lower Manhattan on a crisp fall morning.

ZAPRUDERIt is because we resist the knowledge that hope sometimes turns to despair in an instant and that tragedy comes out of nowhere on a beautiful day, and paradoxically because sometimes we need to confront that very truth, simply to see the thing that we feel cannot happen in order to touch for a moment the very limits of what we know about life and to remind ourselves of the fragility of it all.

REHMBeautifully written, Alexandra. Tell me briefly how your writing this book has affected your family.

ZAPRUDERI think in the best way it has given our family a story that we didn't really have about the Zapruder film. You know, we all grew up, as I said, with an awareness of it but not knowing very much about it, knowing less than many people did. And, you know, I have children, and my brothers have children, and my cousins have children, and there is the desire -- it isn't that I set out to do it for this reason, but in the course of writing the book I came to understand that there was something to pass on, that there was a virtue in having a coherent narrative, a story of our family's place in history, of the life of the film and the way the film -- what the film meant that was important for us to claim and for us to be able to give our children.

REHMI for one am glad you've written the book, Alexandra.

ZAPRUDERThank you so much.

REHMAnd thank you. Alexandra Zapruder, her book is titled "Twenty-Six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film." Thanks, all, for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.