Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

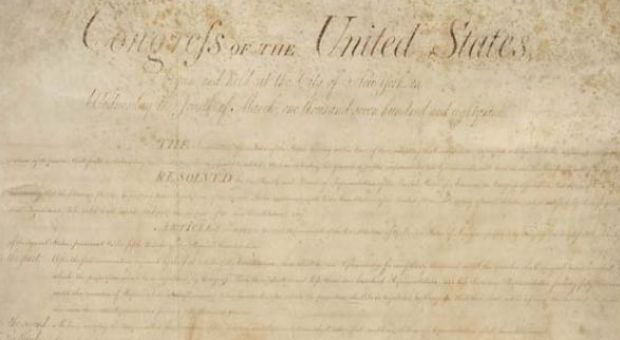

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is key to American law and government. It consists of the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution and contains guarantees of essential rights and liberties of individual citizens omitted in the crafting of the original document. A closer look at the Bill of Rights and the diverse interpretations it evokes today.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us, I'm Diane Rehm. The Bill of Rights was set up to limit the power of the U.S. Federal Government and protect the liberties of the people. It consists of the first 10 Amendments to the "Constitution." As part of our continuing series, "The Constitution Today," we look at the history of the Bill of Rights and what it means to current day American society and law.

MS. DIANE REHMJoining us here in the studio, Nina Totenberg of NPR, A.E. Dick Howard of the University of Virginia and Susan Bloch of Georgetown University. Joining us from the NPR New York Bureau, Jeffrey Toobin of The New Yorker and CNN. Of course, we invite your contributions this morning. Join us on 800-433-8850, send us your email to drshow.org, join us on Facebook or Twitter. Good morning to all of you.

MS. NINA TOTENBERGGood morning Diane.

MS. SUSAN BLOCHGood morning.

MR. A.E. DICK HOWARDGood morning.

REHMGood to have you here. Dick Howard, very briefly, tell us what's in those first 10 Amendments in the Bill of Rights.

HOWARDDiane, I can assure that they are brief and to the point of...

REHMOkay.

HOWARD...mercifully short as legal documents go. This is one that anybody can get his or her hands around.

REHMGood.

HOWARDAnd there are 10 of them, as you say, and the first one is the one that obviously attracts most people's attention because that protects or guarantees very basic rights such as speech, press, religion and the like. But then there are some amendments that also deal in particular with criminal justice with procedural guarantees and they stated broadly are essentially what James Madison and the founders of these documents thought to be the core values of a free people.

REHMRight to keeping bear arms, protection from quartering of troops, protection from unreasonable search and seizure, due process, trial by jury, civil trial by jury, prohibition of excessive bail, cruel and unusual punishment, protection of rights not specifically enumerated in the "Constitution," powers of states and powers of the people. Jeffrey Toobin, which parts of the Bill of Rights are the most relevant today?

MR. JEFFREY TOOBINWell, I -- all I was -- I'm just following along because I brought my copy because I didn't want a Christine O'Donnell type of embarrassment at any point here.

REHMI understand.

TOOBINBut, you know, I -- I don't -- what's the most important? I suppose the First Amendment is the most important because that allows us to complain loud enough so that if people are distorting the rest of the "Constitution," the people in power can be changed. But, you know, I think what is so interesting about reading the "Constitution" is that, first of all, it doesn't take very long, as Dick pointed out, and also it's a system.

TOOBINI mean, the parts work together and, you know, what is so striking about reading the Bill of Rights again is that it is really a series of limits. It is what I suppose modern folks would call a Libertarian style document in the sense that it's a list of things that the Federal Government cannot do in order so that citizens may be left alone. And what always strikes me in reading it together is that it is really very clearly a political document aimed at limiting the power of the Federal Government.

REHMAnd Nina Totenberg, what do you believe Americans should know, most importantly, about that Bill of Rights?

TOTENBERGWell, I actually think that one of the things that American citizens should keep in mind is that after the founders wrote the "Constitution" and the Bill of Rights, they immediately disagreed among themselves about what it meant. So it is no surprise that today people disagree about what it means and when you hear people say, it should only mean what the founders intended at the time, they didn't agree on what they intended at the time, so it's a really -- Constitutional Interpretation is a really broad area and there -- it has lots of room for disagreements.

REHMAnd Susan Bloch, why was it created in the first place?

BLOCHWell, it's interesting, the framers of the "Constitution" didn't believe they needed a Bill of Rights and, in fact, didn't have one. In their view, it was unnecessary because the Federal Government was a government of limited powers and there was no need to have this explicit limitation. It was only as the states were ratifying it that they demanded as a condition of their ratification that the -- Madison and the others agree to provide a Bill of Rights when the first Congress would meet. And so in fact what happened is the original "Constitution" had no Bill of Rights. The first -- one of the first things that the members of the brand-new Congress did was proposed actually 12 Amendments and...

REHMAnd two of those?

BLOCHTwo of those did not get ratified...

REHMRight, right.

BLOCH...by the complex process we have for amending the "Constitution," but the first 10 -- or the 10 that we have were ratified. The 11th actually got ratified, but only in 1990. Many, many years later and the 12th has never been ratified.

TOTENBERGYou don't mean 1990?

BLOCHI do.

TOTENBERGYou do? The 11th Amendment?

BLOCHNo, no, I don't mean the 11th Amendment, I'm sorry. Of the 12 that were initially proposed, 10 were immediately ratified. Of the initial 12, the 11th, it's now the 27th, but it just got ratified.

TOTENBERGYes. Yeah, I wanted to make it clear, I'm sorry.

REHMThank you. Thank you for that clarification.

BLOCHSorry.

REHMWhat were the precedents for the Bill of Rights? Dick Howard.

HOWARDWell, Diane, it's interesting that in the era in which the framers worked, they already knew about Bills of Rights. The English had a Bill of Rights in 1689, at the time of the so called Glorious Revolution. That was in effect a parliamentary struggle against the Stuart kings and so they came up with a Bill of Rights, which by the way, you will find has provisions, some of which occur in our Bill of Rights. For example, the right to bear arms, the not questioning legislature speech in other places, cruel and unusual punishment, those all come from English law. The more immediate precedence for the framers at Philadelphia were the state Bills of Rights, in particular George Mason's Declaration of Rights for Virginia 1776.

HOWARDAnd I think those documents were important because they show a transition from an English understanding of Bills of Rights, the sort of notion of ancient practice in English Constitutionalism, to something that was more grounded in natural law, natural rights. It's interesting that in Virginia, they actually drafted the Declaration of Rights first and then when onto the business of drafting a "Constitution" for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the understanding being rather like John Locke and the "Social Compact," that rights precede government. That people, we don't depend on government for our rights. It's not given to us by government. We have them because we're human. And then so the Bill of Rights are in effect a way or restating those rights and saying government has to respect them.

REHMA.E. Dick Howard, he's at the University of Virginia, he's professor of law and public affairs. Susan Bloch, Professor of Law at Georgetown University. Nina Totenberg, NPR's legal affairs correspondent. and by line with us from New York, Jeffrey Toobin, he's staff writer at The New Yorker, senior legal analyst for CNN. Do join us, I look forward to hearing your questions and comments. Jeffrey Toobin, back to you. What do you perceive as the most misunderstood portion of the Bill of Rights?

TOOBINWell, I don't know if it's misunderstood exactly, but I think the changing nature of what the Bill of Rights means is probably best illustrated in contemporary terms by the Second Amendment because, you know, we spent decades, those of us who went to law school in the '80s and -- or before, thinking that the Second Amendment did not guarantee individuals the right to keep and bear arms.

TOOBINBut, you know, we've had several presidents elected who believed differently, who thought that there was a personal right granted by the Second Amendment. They appointed justices who shared that view and now it is quite clear that the Second Amendment, as interpreted by the current court, does give individuals a right to keep and bear arms and it is not at all clear what, if any, gun control laws are still Constitutional. So the fact that the Bill of Rights says a lot of things, doesn't mean that its meaning doesn't change sometimes dramatically over the years.

REHMNina.

TOTENBERGAnd another example of that is Campaign Finance Law. You know, for 100 years, it was understood and as a sort of given that it was Constitutional to ban corporations and unions from spending on candidate elections. And this year, the court by a five to four vote said, that isn't true. So, you know, we had the court reverse itself on school integration, you know, on segregation. You may have different views on (laugh) campaign finance, the Second Amendment right to bear arms. I suspect there are very few people who have a different view about Brown v. The Board anymore, but when it happened in 1954, it was extremely controversial. Virginia shut down its schools rather than comply.

REHMSo you've got an evolutionary process even in the Bill of Rights, Susan Bloch?

BLOCHThat's true and as Nina pointed out earlier, the people who wrote the Bill of Rights and the "Constitution" generally didn't agree on everything as to what the interpretation was. So it is a living document and as technology changes, as circumstances change, the interpretation changes.

REHMSusan Bloch, she's professor of law at Georgetown University. We'll take a short break. When we come back, we've got lots of callers. I look forward to speaking with you.

REHMAnd welcome back. We're continuing our series on "The Constitution Today." And we have with us, as we concentrate today on the Bill of Rights, Jeffrey Toobin, he's the staff writer at The New Yorker, senior legal analyst for CNN, Susan Bloch, professor of law at Georgetown University, Dick Howard, he is at the University of Virginia and board member at James Madison's Montpelier and Nina Totenberg, NPR's legal affairs correspondent. Nina, before we open the phones, let's talk about the First Amendment, what it says and how it has evolved.

TOTENBERGIt says Congress shall make no law respecting freedom of speech, religion, press. Now, there are absolutists who say no law means no law, but in our law, that has not prevailed. There are circumstances you can't shout. You can fire in a crowded theater, you can regulate the time, place and manner of speech. It's also -- there's also a conflict between -- in the religion area, between freedom of religion, freedom to exercise a religion and Congress making no law because sometimes if you make no law, you are affecting -- you can make some law to try to, for example, make it easier for people to worship. When you do that, though, you may be favoring religion as opposed to not religion. And so there are those kinds of conflicts.

TOTENBERGCongress, for example, passed a law -- I don't know -- in the 1990s sometime. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act got struck down basically 'cause it -- it had too much favoring of religion and so there's lots of room in the First Amendment. I want to say one thing about the free speech area, though. It's really interesting and this is true in other areas of the Bill of Rights. Some pretty odious people have exercised their rights and the court has said, you have the right to do it.

TOTENBERGAnd it's one of the reasons we have life tenure for federal judges and for the court and the "Constitution" allows you not to take away their salaries, to reduce their salaries, to give them some protection so they can do those unpopular things that reflect a larger sense of values for all of us. So that when somebody very odious has the right to speak, so do I, who may be slightly less odious.

REHMDick Howard, do you want to comment?

HOWARDYes. I think my nomination for the most misunderstood provision of the Bill of Rights would be the establishment clause of the First Amendment. There's only one press clause, one speech clause, one assembly clause, one redress of grievance clause, but there are two religion clauses. Now, that's not redundancy. I think the framers understood what they were doing, certainly James Madison did, in putting free exercise of religion side-by-side with the antiestablishment principle.

HOWARDFree exercise is not too hard to understand. It may be hard to interpret and practice, but establishment means if you like separation between -- the wall of separation between church and state. Now that's not the language in the First Amendment, but we understand that's what it means. And I think if you wanna understand what religious freedom is about in America, it's not enough to talk about free exercise. It's important to recognize that the other pillar of religious freedom is...

TOTENBERGHe says this better than I did.

HOWARD...the establishment clause.

REHMAll right. I'm going to open the phones and take a question on that issue. First to Bob, who's in Cleveland, Ohio. Good morning, sir.

BOBHi. I've never understood this hard line between religion and the "Constitution" and I was really surprised at the laughter that accompanied Christine O'Donnell's answer about separation of church and state. I know when I was in the military, we had churches on the bases, we had chaplains. During boot camp, we were pretty much forced to go to mass every Sunday. The Senate has -- or the Congress, they have a chaplain and they start each session with a prayer. And I understand that Thomas Jefferson, when he was President, he used to hold religious services in the White House. So the people who -- it seems like, back from the founding of the "Constitution," there was no hard line between church and state and in many aspects of our government today, there's no hard line.

REHMDick Howard.

HOWARDWell, there's no hard line. I think the wall of separation is a metaphor. It's not meant to decide actual cases. Take the case, the instance of chaplains in the military. It's been long understood that if you take people and put them in uniform and send them off to military bases, you must not separate them from their spiritual advisors. And therefore, in order to fulfill the promise of free exercise of religion, one pays military chaplains.

HOWARDAt the margin, certainly, there are tensions between free exercise and establishment and I think those have to be reconciled by way of occasional accommodation of religion, but this doesn't undermine the fundamental principle that government ought not to be in the business of, let's say, channeling money to religious organizations, it ought not to prefer one religion over another. The fundamental principle still yields to exceptions.

TOTENBERGThere's one other thing we have to remember when you look at the broad sweep of American history. Initially, the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states. They only applied to the federal government.

REHMRight.

TOTENBERGAnd only really in the 20th century did the court begin applying them one-by-one to the states so that the same rules apply to the states that applied to the federal government. So the states, you know, way back when could've had laws that did limit speech, did limit some -- you know, did impose some religious practices, like prayer in schools. But the court one-by-one has said, we're a system of one country, one set of laws and the Bill of Rights does apply to the states.

REHMNow, Bill from Galax, Va. asks, "Has the Supreme Court ever made a ruling on the amendments only to reverse itself in four years?" He's thinking about campaign finance and how corporations can now donate anonymously. Jeffrey Toobin.

TOOBINWell, the court reverses itself with some regularity. Perhaps the most famous and most dramatic reversal that the court ever did, it took place during World War II when there was a case about whether Jehovah's Witnesses could be forced to say the pledge of allegiance or salute the flag without being expelled from school. Jehovah's Witnesses wanted to be excused from that because they had a religious objection. And there was a case right before the war where Justice Felix Frankfurter said, this is part of going to school, you have to do it or you get thrown out.

TOOBINAnd during World War II, in what is perhaps my favorite opinion in the whole history of the court, Burnett v. West Virginia, Justice Robert Jackson said, you know, we do not impose ideological conformity in this country. If your religious beliefs require you not to say the pledge, we've learned what happens when authoritarian governments take over, we're not going to insist on that. That was a very quick reversal. As for Citizens United, I wouldn't hold my breath for a quick reversal of that one.

REHMJust to follow up with you, Jeffrey Toobin. You mention the Second Amendment. Can we talk about what the intent of the framers was regarding the Second Amendment? Susan Bloch.

BLOCHWell, can we talk about it? Yes. Will we agree? No. As was said previously, for up until very recently, we thought the Second Amendment just gave the right to bear arms so as to protect the states from federal government so that states could have their own militia, but it was not an individual right to bear arms. But what we learned a few years ago from the Supreme Court is that that interpretation was wrong. And, in fact, it is now held to be an individual right.

BLOCHAnd most recently, the court said, that it's not just a right vis-a-vis the federal government, but the Second Amendment now, too, is incorporated so that it applies to the states, as Nina was speaking earlier, about the notion of these rights being incorporated. We now have a news case that says Second Amendment is individual right vis-a-vis the states as well as the federal government.

REHMDick Howard.

HOWARDDiane, I think the most remarkable transition and interpretation of the Bill of Rights took place during the Warren Court's era in the 1960s. As Nina pointed out, the Bill of Rights originally applied to the federal government only. The Supreme Court made that clear. It was only after the adoption of the 14th Amendment that it began to be possible that the Bill of Rights might apply to the states. And as late as...

TOTENBERGYou should say what the 14th Amendment is. Fourteenth Amendment...

HOWARDFourteenth Amendment is the one that says, that no state shall deny due process of law or equal protection of the law or privileges and immunities of citizenship. Now, that clearly applied to the states, but it didn't specifically reference the Bill of Rights. Justice Black, during the 1940s, had an argument. He said, I -- in my judgment, the 14th Amendment's due process and privileges and immunities clauses apply to the states, all of the provisions of the Bill of Rights. Now, he was never able to get four other votes on the court to sell that proposition wholesale.

HOWARDBut starting in about 1961, in one case after another, the Supreme Court began holding that this amendment and that amendment and that amendment do apply to the states. For example, the right to have counsel appointed if you're not able to afford one used to be decided by the court of a purely ad hoc basis. But after 1963, Gideon v. Wainwright, the court said, it's a universal rule. So basically, we passed a real threshold in the 1960s so that nearly every one of the procedural guarantees of the Bill of Rights now apply to the states by way of the 14th Amendment.

REHMSo what happened to the Second Amendment as we evolved, Nina?

TOTENBERGWell, interestingly, there were very few cases that went to the Supreme Court. I think there was one in the '30s about machine guns, where the court said, yeah, you can ban machine guns for individuals, but there were almost no cases and it really was a given. It's very hard to convince people that even in my reporting lifetime in the 1980s, I remember doing a piece about this Chief Justice Berger gave an interview to Parade Magazine.

TOTENBERGIt said, it's just silly to suggest that the Second Amendment is an individual right. I think Robert Bork said that. so -- but over time, it became a big sort of political issue and a kind of a -- an intestinal part almost of conservative jurisprudence in -- off of the bench, I would say. And eventually that migrates to the bench and -- so the people that conservative Republican presidents are appointing came to accept that idea and when they look at history, they saw something different than what people had accepted for centuries. Not decades, centuries.

REHMNina Totenberg, NPR's legal affairs correspondent. You're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Jeffrey Toobin, do you want to weigh in?

TOOBINWell, I'd just like to point out, you know, what Susan said that, you know, of course the "Constitution" is a living document that changes in meaning over time. That is a very well established view. It is also intensely controversial.

REHMExactly.

TOOBINAnd the Republicans and the Judiciary Committee spent a great deal of time haranguing Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan accusing them of believing in a Living Constitution because that is now an article of faith that that's a bad thing if you are...

TOTENBERG...and vice versa.

TOOBIN...a conservative. And vice versa, although it's interesting that the Democrats don't embrace the Living Constitution all that much. They -- they're sort of in a half-hearted way say, well, you know, Brown v. Board of Education was right and but that other than that, they don't...

TOTENBERGWell, you remember -- but Jeffrey, when -- I remember when John Roberts was being confirmed. He was asked more than once whether he thought the "Constitution" was a living document and he was asked that by Democrats and he gave, as I recall, an answer saying that, yes, he did think it was a living document under certain circumstances.

TOOBINI -- you know, Nina, I, as usual, trust you implicitly...

TOOBIN...don't remember that exchange particularly, but I have been struck by how, you know, Living Constitution has become an epithet...

TOTENBERGYeah.

TOOBIN...I mean, an outright -- you know, assumed to be an incorrect way of looking at the "Constitution" in recent years and I think that's just, you know, an example of how controversial the "Constitution" is day in and day out.

REHMYou know, I must say the one amendment that confuses me the most is the Ninth which offers protection of rights, not specifically enumerated in the "Constitution." So what does that do? Does that sort of say everything we've said so far, now we're going to cover everything else that we haven't said? Susan.

BLOCHWell, the Ninth Amendment is an enigma. Judge Bork called it an inkblot and said, basically, it doesn't mean anything. You can read anything into it so therefore, it means nothing. The court doesn't pay much attention to it in part, I think, for the reason that you -- that led to your question of does it make everything else in the document totally irrelevant because the Ninth Amendment...

REHM...everything is covered.

BLOCHRight. So it's a constant debate and the reality is, it doesn't have -- it doesn't have teeth.

REHMHas it come up in Supreme Court cases onlooking?

TOTENBERGYes. It was actually relied on prior to Roe v. Wade, when the cases leading up to that, they started as, you know, challenging state bans on contraception. That was sort of the prelude to Roe v. Wade. And Justice Goldberg relied on the Ninth Amendment to say that people had an inherent right to decide whether to have children or not. He relied on the Ninth, but the court did not and I think it's one of the only situations where people tried to read something into it and then they backed off.

REHMDick.

TOOBINBut...

HOWARDDiane, I think...

TOOBIN..I’m sorry. Okay.

HOWARD...I think that Susan is quite right. The Ninth Amendment has been rarely invoked in Supreme Court cases and I think one reason is, aside from its being enigmatic, is that the court's got the due process clause. And when you've got the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, that's the one the court has used in cases like Griswold dealing with contraception, Roe v. Wade dealing with abortion, on and on they've created a whole panoply privacy rights, autonomy rights even as recently as Lawrence v. Texas where they held that gay rights were protected by the "Constitution." The due process clause has been so malleable and so expansive that in effect, it's done the job, which might have been done otherwise by the Ninth Amendment.

REHMNina or Jeffrey?

TOTENBERGJeffrey has something he wants to say.

REHMOkay.

TOOBINNo, I -- the moment passed.

TOTENBERGIt made Jeffrey speechless.

REHMJeffrey Toobin, he's staff writer at The New Yorker, senior legal analyst for CNN. We'll take a short break. When we come back, your calls, your comments. I look forward to hearing from you.

REHMAnd we're back with our continuing series on "The Constitution Today," concentrating on the Bill of Rights. Here's question on Facebook. "Freedom of speech versus hate speech, does Europe have it right? Should we ban hate speech?" Jeffrey Toobin.

TOOBINWell, I think this is one of the great examples where you can have a civilized country with different rules than ours. In Germany, which is a free and vibrant democracy, it is simply illegal and you can go to jail for advocating Nazism. And, you know, given German's history, you can certainly understand why they have a rule like that. But in this country, there is really a very strong tradition of not limiting speech on the basis of its content, political or otherwise.

TOOBINAnd, you know, I'm an American. That's the tradition I'm much more comfortable with. I don't think hate speech should be limited in any way that's usually talked about, but you can see why different countries have different rules. Canada has different rules about this sort of thing, but I think our rule is much more easy to administer and much more in keeping with our limited government tradition.

TOTENBERGAnd anyway, what's hate speech? Try defining it (laugh).

TOOBINWell...

REHMYeah, yeah. All right. To Winston-Salem, N.C. Good morning, Timothy.

TIMOTHYGood morning. My question concerns the part of the First Amendment that guarantees freedom of religion. Was there ever a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that freedom of religion also meant by implication freedom from religion? What was the case and when was it made -- when was the ruling made?

REHMDick Howard.

HOWARDWell, I think there've been a long line of cases that suggest not that the country is free from religion, but that the government may not force religion upon people or endorse religion over non-religion or one sect over another. That really began to percolate in the mid-20th century starting with school prayer and Bible reading and sort of thing. I think the court has been particularly concerned about if you like captive audiences, school children. I think it's less concerned about religious speech in more public places, but in effect, the court has tried to prevent government from using its coercive power to force people to accept one view of religion or another. So yes. There are a number of Supreme Court cases which do just that.

REHMThe Eighth Amendment says, there is a prohibition of excessive bail and cruel and unusual punishment. Does that in any way, Susan, rule against capital punishment?

BLOCHWell, the question is complicated in part because also in the "Constitution," where we have the due process clause, the -- it says that the government shall not take away life without due process. And so those people who say -- they say, well, that means that the government can take away life so long as it complies with due process. So in that view, the Eighth Amendment does not prohibit the death penalty. On the other hand, some, like Justice Marshall and Justice Brennan, have said that the way the death penalty is administered is so haphazard and fraught with prejudice, really, that whether -- you know, maybe if there were a perfect system you could have the death penalty, but there has never been a perfect system. No one seems to know how to make a perfect system. And so their view is that the Eighth Amendment does prohibit...

TOTENBERGBut there's nobody sitting on the Supreme Court today who has said that he believes that capital punishment or she believes that capital punishment is per se unconstitutional. And even...

BLOCHAlthough Stevens...

TOTENBERGNo, he didn't. He didn't. Justice Stevens, who just retired, and did an interview with me in which he talked about this extensively and he said, I voted to uphold the death penalty in the mid-1970s because we put such -- we were putting such strict rules in on who could -- on what prosecutors could do in selecting a jury and other rules that protected the whole process. And the court more recently has taken away those rules and made it a more lopsided system. And in view of that, I could not support the death penalty. But he said, if they had stuck with the...

REHMHuh. Interesting.

TOTENBERG...the way they had been doing it in the '70s...

REHMYeah.

TOTENBERG...he said he thought that he would still be supporting the death penalty.

REHMDick Howard.

HOWARDDiane, the cruel and unusual punishment provision is the paradigm example of what we might call the Living Constitution. It is true that the Supreme Court has stopped short of outright abolition of the death penalty, but starting in the 1970s and continuing to the present time, they've had case after case deciding just what the meats and balance of capital punishment are. And to give one fascinating example, in 1989, in two cases, the court upheld the death penalty for youthful offenders and for the somewhat mentally retarded. And then in cases in 2002 and 2005, the court itself overruled its own precedence to show how this concept continually evolves.

REHMLet's go now to St. Louis, Mo. Good morning, Dimitri.

DIMITRIGood morning, Diane. In listening to your discussion, I wanna release the catch on my 45 when I hear people talking about the "Constitution" because it usually starts out like what it really means. So I think the "Constitution" has become useless at this state. My question to your panel is, Aristotle wrote a book -- an essay called "Politics" and he points out the fact that a monarchy is preferable to a democracy, that democracies doom to failure. And my question is, what does the panel think about this?

REHMJeffrey Toobin.

TOOBINI just can't get over that caller's voice. He sounds just like William Rehnquist...

REHMMm-hmm.

TOOBIN...who is no longer with us, but in the...

TOTENBERGYou're right. You're right.

TOOBIN... great sort of mid Wisconsin, Midwestern accent that William Rehnquist had, which is neither here nor there. But I heard...

TOTENBERGI don't think he had a 45, either (laugh).

TOOBINWell, I don't know, but -- and I urge you to keep that 45 holstered, if at all possible, even though it's now clear you have a right to have it. You know, I don't know. That question's above my pay grade. It takes someone else. That's too hard.

REHMWhat do you think, Dick Howard?

HOWARDWell, you know what that question puts me in mind of is forms of government which have concerned us from the time of Aristotle to the present time. And I think that in talking about the Bill of Rights, I think we ought to remember that Madison, in particular, was concerned that Bills of Rights by themselves were not enough. So he and framers put into play -- and this is responsive to the question about the "Constitution," that they understood the checks and balances, separation to powers, federalism, structural limitations, limiting power so that you play one faction off against another.

HOWARDThese were thought to be among the primary ways of protecting individual rights. You don't just rely on the enumeration rights and the Bill of Rights, you limit power so that government becomes limited government and that's one of the -- surely the key functions of the "Constitution."

REHMNina.

TOTENBERGAnd, you know, there are some things that we do in modern governance that people think are in the "Constitution" that are not, that lead to a lot of gridlock. For example, the filibuster. It's just a custom of the Senate. It's a rule of the Senate, it is not in the "Constitution." And I'm sure there are many other rules in, you know, the modern administrative state that are not in the "Constitution."

REHMOn the other hand, as we talked last week in the first of our series, one criticism of the "Constitution" today is that it is so difficult to amend. Now, what's your thought on that, Susan?

TOOBINThank God for that. That's all I can say.

TOTENBERGThat was Jeffrey -- that was Jeffrey Toobin.

TOOBINYes. You know, when you -- well, yes. Well, when you look at, you know...

BLOCHJeffrey, she called on me.

TOOBIN...the passing -- the passing political fancies that we all get involved with, you know, it is good that it's hard to amend the "Constitution." This is our foundation document that has stood us in very good stead for well more than 200 years. And other than very fundamental rules like, you know, should women get the right to vote, should 18-year-olds get the right to vote, which are some of the more recent amendments, I think it is much better to keep contemporary political debates in Congress where they belong and rather than, you know, tying the country's hands for generations, which is what you do when you amend the "Constitution."

REHMDo you wanna add to that?

BLOCHWell, no, I agree with what Jeffrey said. I just wanted to point out that after the first 10 Amendments that we're talking about today, primarily, in the next 200 years, we've only added 17 more. So it is very, very difficult...

REHMYes.

BLOCH...and they made it deliberately difficult and...

TOTENBERGAnd two of them were about drinking (laugh).

BLOCHRight.

REHMAnd we have another message on Facebook from Thomas who wants us to discuss the 10th Amendment and what motivated its inclusion in the Bill of Rights. Dick.

HOWARDThe 10th Amendment is the one that says the power's not delegated to the United States nor prohibited to the state's reserve to the states or to the people. Now, that's also a bit enigmatic, but it, among other things, was clearly meant to -- assuage the concerns of critics of the original "Constitution," the so-called anti-federalists. They were concerned that the "Constitution" would create an over-weaning federal power, a teratical central government.

HOWARDThis was meant to say, no, the state still exists, they have a constitutional integrity, they do have rights of their own. Now, that particular amendment seemed to have been read out of the "Constitution" by the Warren Court back in the '60s. It really came back by way of William Rehnquist and others in the 1990s. It's really part of the sort of balance wheel of American federalism.

BLOCHYeah, it...

TOOBINBut I think it's -- if I -- I'm sorry, if I could just jump in here.

REHMSure.

TOOBINAgain, the contemporary political relevance of the Ninth and 10th Amendments both are regularly cited by the Tea Party movement. I mean, the Tea Party movement, whatever you think of it, thinks a lot about the "Constitution" and the Ninth and 10th Amendments as checks on federal power is something that people in the Tea Party often discuss. Now, whether they could give that any teeth or make a practical change to how the government operates is another question, but it is regularly cited as a check on federal power by those folks.

REHMSusan?

BLOCHNo, I agree with that. I mean, at one point in the 1940s, the Supreme Court just said the 10th Amendment basically it doesn’t say anything. It's a truism. It just says the power you didn't give to Congress, you didn't give to Congress, but it doesn’t really say anything. Today, there's more teeth in the 10th Amendment. Laws are being -- Congressional laws are being struck down for, quote, "commandeering the states," for forcing the states to do things, so...

REHMGive me an example.

TOTENBERGThe Brady Bill -- the Brady Gun Control Bill.

BLOCHThe Brady Bill was one, a small part of the Brady Bill was struck down on that. Federal government -- I mean, a federal law dealing with waste was -- part of it was struck down because it was forcing the states to take title to the waste. So there's -- there's teeth in the 10th Amendment now that...

TOTENBERGAnd yet we do have to say -- you do have to -- I mean, when you're looking at this, you do have to say two things. We fought a civil war over states' rights and the idea of the federal government as bigger, stronger, better, whatever, maybe not better, but bigger and stronger and preemptive one and so that battle, to some extent, people read parts of the "Constitution" and they forget about the Civil War amendments that give the federal government power to regulate the states. That's number one.

TOTENBERGAnd number two, going back to the Ninth Amendment, it often is a question of whose ox is being gored. There was a period of time not that long ago when liberals loved the Ninth Amendment because they wanted to read all kinds of rights into it, personal rights into it. And they saw it as a sort of expansive thing. Now, it's conservatives or Tea Party movementers. It depends.

REHMNina Totenberg of NPR. You're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Here's an e-mail from Hank, who says, "Is the Second Amendment a two-part or a one-part amendment? If two parts, a right to bear arms and a right for militias, or one-part, arms with and for militias?" Dick Howard.

HOWARDWell, it's very interesting. The Second Amendment has its roots in the English Bill of Rights and then in American state constitutions and it's a wonderful example of what original intent yields whatever you think it means. It gives rise to law office history. You read the relevant parts of the historical interpretation and it seems to me, the language is pretty clear that you have a clause at the beginning referring to the militia which qualifies and modifies the right of the people to keep and bear arms.

HOWARDBut the respective camps on the U.S. Supreme Court in the D.C. v. Heller case, one camp said, oh, it means individual rights. The other camp said, it means collective rights. They read the same history. They came up with totally different answers, so I guess the answer at the moment is the majority -- the five person majority in the court has collapsed these two phrases into one.

REHMIs that how you see it?

BLOCHThat is what the five-four majority did. The amendment reads, a well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed. Most people thought that that meant that in order to keep a well regulated militia, people could have arms, but the way the Supreme Court has read it is they basically ignored the part about a well-regulated militia.

REHMNina?

TOTENBERGWell, I think that the court, you know, when I went to the argument in that case, Justice Kennedy, who was pivotal in this, basically said, who said -- who doesn't believe that you have the right to have a gun in your house to go -- to defend yourself or to go hunting? That's sort of a intrinsic guttural understanding. He -- that seemed to be what he was thinking. And we have yet understand how far the court believes that states and the federal government can go in regulating that. Can they limit carrying, you know, can they -- a concealed weapon? Can they limit the kind of weapon you have? Can you have a street sweeper at home? You know, those questions have yet to be answered.

REHMAnd it seems to me that as you think of the creation of the "Constitution" as creating a document that helps us to get along as a nation, here we are 250 odd years later and we're still arguing.

TOTENBERGIsn't that good?

REHMI guess it's good, but it does raise as many questions as it answers, which is why I think this series is so important for me and I hope for all of you. Nina Totenberg, Dick Howard, Susan Bloch, Jeffrey Toobin, thank you for your time, your expertise and your presence. And thanks, all, for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

ANNOUNCER"The Diane Rehm Show" is produced by Sandra Pinkard, Nancy Robertson, Susan Nabors, Denise Couture and Monique Nazareth. The engineer is Tobey Schreiner. Dorie Anisman answers the phones. Visit drshow.org for audio archives, transcripts, podcasts and CD sales. Call 202-885-1200 for more information. Our e-mail address is drshow@wamu.org and we're on Facebook and Twitter. This program comes to you from American University in Washington. This is NPR.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.