Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

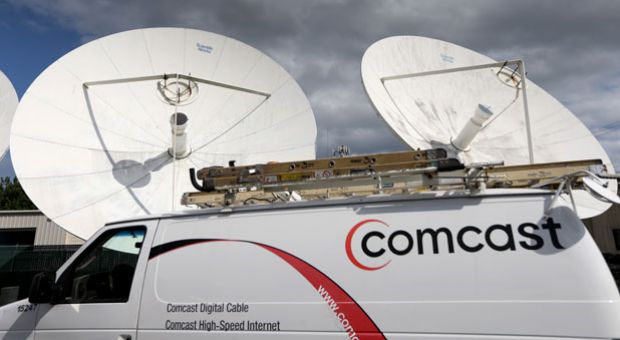

A Comcast truck is seen parked at one of their centers on Feb. 13, 2014 in Pompano Beach, Fla. Comcast announced a $45 billion offer for Time Warner Cable on Feb. 14, 2014.

Last week, the two largest cable TV operators announced plans to merge. The proposed new entity would have approximately 30 percent of all national pay television subscribers and also about a third of all broadband Internet subscribers. Some consumer advocates say that if the merger is approved, cable TV bills will go up and the new company will have too much control over program content, high speed Internet access and price. Regulatory approval is not a given. Both the Department of Justice and the FCC will weigh in. Diane and her guests talk about the proposed mega-merger and what it means for consumers.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. In the cable TV industry consolidation has been the rule and last week was no exception. The country's two largest cable TV providers, Comcast and Time Warner, are proposing to merge, a move that's now subject to regulatory approval. Joining me to talk about the plan and its implication for consumers, Berin Szoka of TechFreedom, Gautham Nagesh of The Wall Street Journal.

MS. DIANE REHMJoining us by phone from Cambridge, Susan Crawford. She's a professor at Cardozo School of Law and a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. I'm sure you'll want to weigh in. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Send us an email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. And welcome to all of you.

MR. GAUTHAM NAGESHThank you.

MR. BERIN SZOKAThank you.

MS. SUSAN CRAWFORDThank you very much.

REHMGood to see you all. And Susan Crawford, if I could start with you, Comcast says that this merger would not limit competition because these two companies operate in different parts of the country. Is it that simple?

CRAWFORDComcast story's a little more complicated than that. Here's the source of their hidden advantage and the reason why it's going to be very difficult for new infrastructure competitors to enter in 'cause after all, that's what we're talking about here, basic infrastructure, not pay TV. Comcast pays half or a third as much for programming as any new entrant would building that infrastructure.

CRAWFORDThat's because they have so many subscribers they get discount volumes -- volume discounts, sorry, other way around. If some new player showed up, they'd have to enter markets at once, both the market for programming and the market to build their basic infrastructure. So making Comcast even huger just widens the gulf, makes it even more difficult for a new actor to show up.

CRAWFORDNinety-one percent of Americans who buy high speed internet access also get pay TV. The relevant market is the bundle and in that market, Comcast has enormous advantages. This merger takes an already terrible situation and makes it quite a bit worse.

REHMLet me ask you, Gautham Nagesh, are there areas in this country where there's actually no cable industry operating at all?

NAGESHThere are areas, especially in the extreme rural portions, like in the northwest, but most, the vast majority of the country has cable available and those areas where there isn't, satellite is usually the choice. However, the issue, as Ms. Crawford referred to, is obviously that Comcast is already the largest cable provider. Time Warner cable is number two and so the question is whether the combined entity would have too much of an advantage over not just their competitors, but content providers who they must negotiate with for the price of content.

NAGESHOf course, we've seen in the TV market, content is what is driving the price, especially things like live sports. So yes, there is definitely an argument to be made that the combined entity would have too much of an advantage for anyone else to ever get in this market. Comcast would respond that most people don't have a choice of cable provider as it is, or if they do, it's usually between a large provider like Comcast and a much smaller provider and so perhaps they would argue that programming would constitute some efficiencies.

NAGESHI think they've put it at about 1.5 billion. It is not the major selling point, but they argue that prices are going to go up no matter who is negotiating because it is the content companies that are driving the prices, people like Disney and Viacom.

REHMAnd Berin Szoka, how do you see it?

SZOKAWell, I'm a lot more optimistic about the market than Susan is in general. I'm also one who thinks that there are plenty of ways of dealing with the sort of market power that she's describing here. So it's certainly true that having larger scale gives you somewhat more leverage in negotiating with programmers. That cuts both ways. That can actually mean that a larger company can get a better deal for its subscribers on programming costs, which, after all, is what has driven up the price of cable television.

SZOKANow, her concern seems to be that the combined company is going to be unmatchable in the combined market for internet service and for video programming service. I think there's a lot we could be doing to make competition easier, make new entry possible. Verizon, for example, has rolled out in 14 percent of the country. She says that's not enough.

SZOKAI would like to have seen them roll out in other places. The reality is they didn't roll out in many cities not because they didn't want to, but because the cities themselves, like Baltimore, made it impossible for them to do so. So what we've seen with companies like Google Fiber rolling out in cities like Austin, Kansas City is that they're doing it where local governments have made it easy, where they've made it possible to use the real monopoly which is the right of way.

SZOKAIt's digging under the street. That's the real problem and I think if we focus on that problem, we can actually have a far more robust broadband competition market. But I would say that today's is pretty robust.

REHMGautham.

NAGESHI think, yes, broadband is definitely going to be the primary focus for regulators because broadband is really the technology of the future. You can do video, voice and data, whereas, obviously, traditional cable is only video. However, the issue with broadband is, one, there is not as much competition as in the video market. You have satellite providers. You have the phone companies. You have the internet and you have broadcast options in video, whereas usually you only have your phone company or your cable company in any given market if you want to choose a high speed internet access for your home

NAGESHOf course, the issue here is whether or not there is a realistically -- we can support more broadband providers in one local market than we do. I was speaking to a veteran anti-trust attorney and he told me, essentially, that cable is the classic sort of argument for a natural monopoly. There is huge barriers to access. There is extreme cost. There's extreme benefits from economies of scale.

NAGESHSo cable companies have always sort of been a natural monopoly and whether that will change is really an open question.

REHMBut Susan, what about people who have cut the cord with cable and who simply want to get their television through internet?

CRAWFORDWell, the thing about this merger is that it's going to increase the power of Comcast to play games with the connections between its increasingly massive network and other networks across the country that are being used by those over-the-top providers to reach consumers. Comcast has so many dials to turn. It could make life miserable for high capacity uses of its network.

CRAWFORDIt can force people to pay tribute. It can make sure that those communications go more slowly than other communications. It's got a lot of ways to play games and it's in its interest to avoid a model where consumers pay directly for head to head competing video because, again, that undermines their source of advantage, which is their very low programming costs that they pay compared to everybody else.

REHMBerin, what about that?

SZOKAYeah, so three quick points. First of all, on the natural monopoly point, Google, Verizon, Century Link, the many companies that are rolling out fiber don’t seem to agree that it's a natural monopoly. If there is a natural monopoly, it's digging under the street and that's a problem that many congressional Democrats have proposed to deal with through smarter infrastructure policy called Dig Once.

SZOKAPut a conduit in there, let anyone deploy. That's a smart way to deal with that problem. Second point, let's keep in mind most people don't really appreciate this, that cable companies don't really compete with each other. They're not in the same markets so we're not talking about any direct effects on competition. Everything we're talking about here is an indirect concern at most because this is not going to change the state of broadband competition at all in any market.

SZOKAIt's about indirect concerns and Susan noted that at the beginning. Now, Susan's concern is that ultimately this deal makes it easier for Comcast, as she said, to play games. But let's just think about the many layers of restrictions on Comcast that are already in place today. So number one, Comcast agreed to many conditions when it bought NBC Universal in 2011 that are intended to address precisely the concerns that she raised.

SZOKAAll of those get extended to Time Warner Cable subscribers through this deal. Like, I think that she should celebrate that as win and I think as a predictive matter, you may see that the company extends those by a few more years beyond 2018.

REHMBut what about pricing? What about the price to consumers? To what extent are we likely to see prices go up because Comcast controls so much of it?

SZOKASure. So let's take a step back and ask why prices for cable service, cable television service, are going up as it is now. Short answer is it's not the broadband companies. It's the content owners. I mean, content is king. CBS CEO said this just last week.

REHMAll right. All right. Susan, do you want to chime in?

CRAWFORDWell, yes. Comcast gets to be more efficient through scale. It is not saying that that's going to add up to lower prices for consumers. Quite the opposite. David Cohen has already said, he's the guy running this operation for Comcast, we're not promising the customer bills are going to go down or that they'll increase less rapidly. Look, we need to look at competition today as people face it in their living rooms. Today, Google Fiber covers .06 percent of American homes.

CRAWFORDVerizon stopped building out after it had reached 14 percent of America. In about 77 percent of the country and in most large metro areas of the country, your only choice for a high capacity information connection is your local cable monopoly and that will be Comcast.

REHMGautham Nagesh, to what extent do you have the regulatory process sort of stepping in here, perhaps placing limits, perhaps not approving this at all?

NAGESHSure. Well, both of those are strong possibilities. If you were to take a poll among telecom lawyers in town, I think most would probably lean towards the possibility that this would be allowed with regulations, but it is far, far too early to say definitively. I've talked to people inside the FCC, which has one side of the authority on this. The other would likely be at the Justice Department, though it could potentially be at the Federal Trade Commission also.

NAGESHHowever, at the FCC, they don't even know that to think about this yet or if they do, they're not telling anyone, at least not at the highest levels, because this is a huge transaction with broad implications and some things like the -- Susan referred to playing tricks with the network, that's the kind of thing that potentially conditions on the merger could seek to address and whether or not that would work, again, is an open question.

NAGESHBut the other -- to Berin's point regarding Google Fiber, Verizon Fios and the natural competitor, natural monopoly, it's worth noting that Verizon is not going into the Fios business and Google itself has also said this is not an area where they see a big part of their business.

REHMAll right. Short break here and when we come back, we'll talk more, take your calls. I look forward to speaking with you.

REHMAnd welcome back. Here in the studio with us, Berin Szoka. He's president of TechFreedom. Gautham Nagesh is with the Wall Street Journal, Susan Crawford, visiting professor at Harvard's Kennedy School and Harvard Law School professor. She joins us from Cambridge. We've had a Tweet from Ryan saying, "Baltimore did no such thing. Sorry, we're just too poor for files Fios."

SZOKAWell, that might be what Baltimore City government wants you to believe but the reality is that Baltimore made it impossible for Verizon to deploy Fios there.

REHMHow so?

SZOKASo when you want to deploy a competitive network in any one of these markets, you have to go through a local clearance process to get approval. That itself can take many years. The deployment in D.C. has been dragged out far longer than it had to be because of that.

REHMAnd you're saying Baltimore said no?

SZOKAWell, they didn't say no. They said, you know, jump through all these hoops and they made it not worthwhile to do. Now, the concern about Baltimore residents being too poor, first of all Verizon wanted to deploy there. They thought it was a good opportunity, just like they thought it was a good opportunity to deploy here in D.C. But if you're concerned about the digital divide, about certain folks not being able to afford broadband, we could have a conversation about how to deal with that. The problem is that these two conversations end up getting conflated so that people somehow think that the way you regulate broadband is necessary to subsidize it.

SZOKAWe could have smart subsidies, we could have broadband vouchers and still work -- and treat broadband as more of a competitive market.

REHMSusan, what happened in Baltimore?

CRAWFORDWell, you know, what's going on with a bunch of these cities is that they are desperate to get Verizon there. Boston, for example, Mayor Menino pleaded with Verizon to show up and couldn't get them to commit. I'm sure there are lots of facts about this that we could dig out, but the fact is we don't today have competition for this basic infrastructure in most large American cities. And that means we're being held back, we're paying too much, we're ending up with not as swift networks as we should have.

CRAWFORDWe should have fiber going to every business in the United States. We should be able to keep up with Korea, Japan, South Korea. We're not getting in that direction the way things are going right now.

REHMYes. And the cable television industry has been shrinking by how much and how quickly? And is that one of the reasons for a merger like this?

NAGESHYes. And we're conflating a little bit broadband cable television. But in the cable television industry they used to control 98 percent of the pay TV industry in 1992 when they wrote the Cable Act. Today that's about 55 percent, a little more than half. The reason is because we've had satellite providers for 20 years. Now we do have things like Verizon files or AT&T U-verse, which are pay TV offered by phone companies. Then also you have cord cutters which are only about 5 percent of the market or, I think, 6 million people at present.

NAGESHBut that's a growing trend. A million people cut the cord last year when exclusively on broadband internet access. In many cases they still have to pay their cable company for broadband but they have still found a way through things like Netflix, Hulu, Apple TV to piece together enough video content that they no -- and broadcast TV, they no longer feel the need to have to pay the $90 on average for cable.

REHMSusan.

CRAWFORDJust two quick points on that. One is that last year about 85 percent of new broadband subscribers went to cable and Comcast took the lion's share. They got 300,000 new subscribers last quarter alone. AT&T lost 26,000. Another point is that this merger makes it even more possible for Comcast to constrain the conditions under which programmers make their programming available online.

REHMHow so?

CRAWFORDWell, we saw this with Time Warner Cable having a dust-up with CBS last year. The reason they were fighting and the reason that CBS yanked its signal in Los Angeles and Dallas and New York was because Time Warner Cable wanted to keep CBS from letting its programming go out online without paying Time Warner Cable. And so we know that as Comcast get bigger they'll be able to keep programmers as a condition of getting carriage on their network from letting online platforms get access. That means Hulu and Netflix and the others won't have access to the programming that would otherwise allow them to compete head-to-head.

REHMBerin.

SZOKAThat very concern was dealt with by the NBC Universal merger condition. So to the extent that you're worried about cable companies doing that, this deal means that those protections are extended to Time Warner Cable customers, because they already apply to Comcast.

REHMLet me ask you the same question I asked Gautham. How likely is it that this deal is going to be approved? And if so, why? If not, why not?

SZOKAOh, I think very likely. I think it's very hard to make an antitrust case against the deal for the reason that I mentioned earlier.

REHM...which is why justice is getting in on it.

SZOKAThat's right, because the antitrust analysis on this is pretty simple. There is no direct head-to-head competition for broadband service. The concerns that Susan are raising are certainly valid ones. They could hypothetically be true but there are plenty of ways to deal with them today. I already mentioned the NBC Universal conditions. We talked about antitrust law. We haven't mentioned the FCC's program access rules. We have a variety of rules to deal with the sorts of concerns that she has.

SZOKASo to block a merger you really have to argue that the rules -- that A. the merger makes things worse than they are today, which I think is a hard case to make, and two, that the existing rules you have are inadequate to deal with those concerns.

REHMSusan.

CRAWFORDSo in a sense were saying, things were terrible already. It's not going to make it that much worse to go through the merger. Look, I'd like to see a different trajectory taken by our leaders in Washington. I think this merger gives the entire country a chance to step back and say, what is going on? How could we allow these very few companies to control our informational destiny? It's as if we're -- all the people in Fort Lee, N.J. trying to get across the George Washington Bridge. There is a bully getting in our way. We're not quite sure how this is happening, but it's a real problem for the country as a whole.

REHMGautham.

NAGESHI'm not sure that it's that easy to classify it in that manner. Because, for example, you could argue that the phone company controls all access to all your information. As it is, we've always had a concentrated market for cable television and broadband. There are a variety of reasons for that. I wouldn't, you know, presume which one if the primary but...

REHMBut isn't that the very reason why AT&T had to break up?

NAGESHYou could say that but then at the end of the day we have really two wireless companies that control the vast majority of the wireless market. And two or three phone companies that control the vast majority of the real backbone. And they're all essentially Bell descendents that have reconstituted themselves. So while there have been legal interventions, there's a sort of natural tendency in this market, and the media market in general, towards consolidation.

NAGESHRegulators have stepped in at different points and you can argue that this is one of those points that they should. But this has been generally the state of this market and where things have gone.

REHMBerin.

SZOKASo let's talk about the AT&T breakup and let's talk about the idea that was once assumed that telephony was a natural monopoly. The reality today is that you have competing networks that are delivering service. So the original cord cutting was cord cutting for your home wire line telephone connection, which is something that now about 40 percent of Americans have done. They've switched entirely to their wireless network, which is a competitive infrastructure. Another quarter are getting their telephone service through a cable company.

SZOKASo that leads me to another form of competition here, which is about not just fiber but about tel-cos competing directly with cable. Susan dismisses that. She says it's not fast enough. She says it doesn't happen in enough markets. But let me put a few facts on the table for you.

REHMBut wait a minute. Let her respond. You speak very quickly. Go ahead, Susan.

CRAWFORDThe median user of a wired high-speed internet access connection used up about 50 gigabytes of data a month. If you try to do that using a wireless connection, you'd spend $500 a month. This is about capacity. These two things don't compete head-to-head when it comes to the services that people use their wires for. And cable has won that market absolutely.

REHMAll right. Gautham, I have a simple question. Why do cable companies -- why does Comcast keep raising its monthly charges?

NAGESHI think it's a combination of two things. One is that definitely content costs more money now. And, again, the driver is live sports. Broadcast networks and...

REHMBut even if I don't take live sports, why am I paying for it?

NAGESHWell, you don't have any option right now. They sell what's called the bundle cable companies. And there are -- there's a longstanding movement led by Sandra McCain in town to basically deliver something called ala carte cable where you can buy individual channels and not pay five bucks a month for ESPN, which is by far the most expensive channel. However, that has never gotten much traction. That's partly because the cable guys are really powerful in town. And that's partly because it's just not a priority for a lot of lawmakers. But ala carte cable would be a solution to that.

NAGESHYou could see the FCC or DOJ push for some sort of condition to loosen up the bundle a little bit. We've seen that happening a little but it's just not been something that's gotten a lot of traction in the past.

REHMHow much will the public be allowed to weigh in on these mergers?

NAGESHWell, the FCC will have open public comments, so anyone who wants to can go to the FCC's website. You can write to your legislator. This is going to be a big deal.

REHMIt's going to take at least a year.

NAGESHYeah, nine to twelve months is what they say and it's going to be hearings, events, everything.

REHMBut wouldn't the DOJ be the first to weigh in on whether this is monopolistic?

NAGESHUsually these reviews occur concurrently. What we have seen in the past is that DOJ under this administration has taken the lead. They've been more aggressive in antitrust than the FCC has. But it's a new FCC chairman. It's a new head of the DOJ.

REHMAnd both the FCC chairman -- well, the FCC chairman is a former lobbyist for the cable companies, is that correct?

NAGESHYes. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler once headed the industry trade group for the cable industry in the '80s, I believe.

REHMWhat does that tell you, Susan?

CRAWFORDI want to stick up for Tom Wheeler here. He's a fine civil servant. He cares a lot about competition. He will do his best. He played that role 30 years ago. You know, he is in a very difficult spot because if he tries to say no to this merger he would have been met with a firepower of Comcast, which is very powerful on all political levels. If he says yes and conditions it, it's been very clear that Comcast can work around any conditions that are imposed on it. And at the basic problem identified by all three of us is that we've got single infrastructure in most American cities that is subject to no real oversight. And this merger makes that situation worse.

REHMGo ahead, Berin.

SZOKASusan says it all the time, it's subject to no real oversight. That's just not true. The fact of the matter is that we not only have the antitrust laws, but while people have said that the D.C. circuit struck down the FCC's open internet order and have portrayed this as a loss for the FCC, the fact is that the FCC now has even more power than it did before that decision. Because while the particular rules that they tried to implement were struck down, the court said that generally speaking they can do pretty much anything they want here so long as they leave some flexibility for negotiation between broadband providers and content companies.

SZOKABut they can still require, for example, that any deal struck be reasonable and nondiscriminatory just as they've done for data roaming between wireless carriers. So Susan' concern that there's just no regulatory oversight, that's just not true. There is regulatory oversight. And to her concern that the competition won't discipline cable companies at all, the way we do competition analysis, any economist will tell you, is to look not only at competition today but at potential competition, which is quite strong.

REHMBerin Szoka. He's president of TechFreedom, and you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Tell me about TechFreedom, Berin. I don't know the organization. I think our listeners would be interested in hearing about its establishment and where the funding comes from.

SZOKASure, Diane. Thanks for asking. So I'm a communications and internet lawyer. I joined the think tank world six years ago. And Tech Freedom is the think tank that I started three years ago. We cover a wide range of issues from telecom policy to privacy. And our message essentially is that the best servant for consumers in the long term is technological change and is competition. And so we've been engaged in this debate in privacy setting up for American's privacy rights. And we get...

REHMAnd where does the money come from?

SZOKAWe get support both from broadband companies and from the very sorts of edge providers that Susan is worried about. So it's both Googles of the world and the Comcasts of the world.

REHMAll right. And Gautham, you wanted to add to that. Oh, I thought you raised your hand. Sorry. All right. Let's open the phones, 800-433-8850. To Karen in Indianapolis, you're on the air.

KARENHi. Thank you for taking my call. We pay for the highest possible speed internet from our cable provider and notice that, you know, after a certain time every night you can't watch Netflix anymore because it doesn't stream. So when we call to complain, we actually got the guy to admit that they slowed it down because it wasn't -- well, I don't know that he actually said because it wasn't from the cable company -- but that they did slow it down. And I was wondering, we don't really have another option of another internet service provider to go to. What recourse do we have? It seems crazy that that's even legal, but what recourse do we have as consumers? What are our options?

REHMThanks for calling, Karen. Gautham.

NAGESHYeah, so recently there's been a lot of talk about this, whether or not Verizon or Comcast or other ISPs are slowing down Netflix specifically. And it's gotten caught up in an issue that people call peering, which is that...

REHMAnd that's spelled P-E-E-R-I-N-G.

NAGESHExactly, peering. And that -- there's these net neutrality rules that say you can't slow down anyone's connection for any type of internet content. But those really only apply over what we call the last mile, the direct connection into people's home. Because Netflix is such a huge user of bandwidth, they have kind of their own internet backbone that they use because they're up to a third or a half at times of peak internet downstream traffic. So Netflix has these -- their own networks that they send content out on. And then eventually they have to connect back up to the network of Comcast or Verizon or whoever home users use.

NAGESHNow there is some reports, concerns that congestion at those points or the way that Comcast and Verizon and other companies are dealing with the peering issue are slowing down Netflix traffic. That is something that I know the FCC is looking at closely.

REHMSo the question, what recourse does Karen have, Susan?

CRAWFORDAt the moment no recourse because the FCC has not yet said that it has authority to do anything about interconnection agreements between these networks. It's not so much that Comcast may be slowing down Netflix, as that it's not building up the connection between its network and Netflix's network. This is, again, just like the George Washington Bridge. There's a connection there that an actor controls and they can decide what capacity is allowed to a certain player.

REHMBerin.

SZOKAYeah, so this is just like the George Washington Bridge except here the mayor of Fort Lee says there's no problem. So here what's happened is this accusation has been made and Netflix itself has come out and said, no, no, really guys, we're not actually being throttled. Calm down. The reality is the problem here is not about throttling. It's not a net neutrality problem. It's what I would call a net capacity problem. As Gautham noted, it's about backend capacity, about how you provide...

REHMYou're saying too many people are on...

SZOKAYeah, the internet was never designed to stream high-speed video. This is the central reality that we're having to deal with. What it takes to make that work is a heck of a lot of infrastructure. It's very expensive. And the question is, how do you make sure that you fund that infrastructure in such a way as broadband providers can't strangle their competitors? And the FCC does have broad power to police those deals to make sure that they're reasonable and nondiscriminatory.

REHMBerin Szoka. He's president of TechFreedom. More of your calls, questions when we come back.

REHMAnd welcome back. Susan, I know you wanted to comment on that last point.

CRAWFORDWell, let's be optimistic. Let's imagine that we had a actual competitive setting. Let's say, we had a wholesale fiber network running into all American cities, which allowed for lots of retail competition. Then it would be in the interests of those competitors to keep their gateways to Netflix. Why? Because their customers want it. That's what should happen in a competitive market. And they would have no incentive or ability to narrow their gates to Netflix. But read for Netflix, any high-capacity app application.

CRAWFORDThis could be a problem for telemedicine, for education, for every new form of ideas that we're going to need new jobs from coming across the wires. Right now we're stuck with a cable actor who's under no compunction to act any differently.

REHMAnd, Gautham, you wanted to make a point.

NAGESHYes. I think that one of the dynamics that people are watching here very closely is the fact that Comcast itself is considered very close to this administration, particularly a couple of its senior executives. David Cohen, who is the executive vice president, is one of the top fundraisers for the Democratic Party. He's hosted a number of event at which the president himself has appeared personally. They are reportedly friendly. I don't have first-hand information on that. But, at any rate, they are -- he was at the state dinner last week for the French President Francois Hollande.

NAGESHAnd then the Comcast CEO, Brian Roberts, he has golfed with the president. He's hosted him at his home for a private event. He has access to the White House. So the Comcast executives have definitely lent Democratic with their donations and they're considered close.

REHMSo, that's behind the scenes. And we don't know what the outcome's going to be there. But here is an email from Pat in Oakland Township, Mich. She says, "We, here, were held hostage to Comcast without competition. We suffered high prices, poor service. Now we have competition, for which I'm thankful I can use it for purchasing power. But no matter how one tries to paint the merger, it's going to cost the individual more and our options will be gone." Berin.

SZOKANo, look, this is big is bad thinking that has prevailed in this country for decades. It's a very natural assumption that somehow a merger is going to make things worse, but it's just not true. So, number one, the FCC, whatever else you want to say about Comcast's political power, the FCC imposed a very tough set of conditions on Comcast when it bought NBC Universal. Those conditions were lauded by public interest groups. They will be extended by this merger to more internet subscribers.

REHMSusan.

CRAWFORDThe day after the Comcast/NBC merger closed, David Cohen announced to investors in Comcast that these rules would have absolutely no limiting function on Comcast's ability to do business. Look, there's a huge variety of stakeholders affected here: people selling programming, consumers, people selling equipment. Really a dampening effect on innovation to have this giant actor become even bigger.

REHMAll right, we're going to go to San Antonio, Texas. Hi, Kitty, you're on the air.

KITTYGood morning. Thank you for taking my call.

REHMSurely.

KITTYWhen I was a student at the University of Texas back in the early 70s getting my degree in communications in the radio-TV film department, one of us asked our professor, Dr. Stanley T. Donner, Why will there be commercials on cable television? And he said, Oh, no. There won't be any commercials on cable TV because we'll be paying for it. In San Antonio, we had the three major channels, plus we were one of the first PBS channels in the country. Small towns like Bryan College Station had cable.

KITTYThey had cable because there was no infrastructure to get the major channels to be transmitted to small towns 100, 200 miles away from big cities. I take DIRECTV because I got burned by bundling my telephone, cable in New Mexico. And it was one of the biggest attorney general's lawsuits against a cable company for so many infractions against the people for bundling. So I don't bundle here in Texas. I just found out that DIRECTV did away with the Weather Channel. So I have no idea what my cousins in Pennsylvania are going through.

KITTYI know that there's a general Northeaster, because local channels don't do the major, you know, evaluations of weather all over the country like the Weather Channel did. They took out the Science Channel without telling me, a customer. I'm paying $90 a month for it. I am about ready to say Adios and go back to rabbit-ears on my television set. And I don't know why we have to pay for 50 channels out of the 250 I get that I maybe watch 20 channels.

REHMAll right.

KITTYWhat can we do as consumers? We also have, in San Antonio, and Internet system, a fiber optic system we just heard about...

REHMOkay. I'm -- I want to get to this question of bundling and then doing away with that. Going to DIRECTV and then having her channels cut. Gautham.

NAGESHYeah. So, as I said, cable bundling is a long-standing tradition and it's something that there's always been opposition to. But we have seen more people jump on to this. As I said, in the past, it has not gained traction. But a lot of people from Senator Rockefeller to Senator Blumenthal have signed on with Senator McCain's bill. They've offered solutions that would try to pry the bundle loose a little bit. We've even seen one or two cable operators offer bundles that were essentially like basic channels plus HBO. Because they realized a lot of people want HBO, but they don't necessarily want all the 500 other channels.

NAGESHSo the thing that's driving all this, is the cost of cable. Cable is, on average, $90 a month according to several groups. And that's a lot of money for today's households.

REHMIt certainly is. And we're back to the question, Susan, of what consumers can do. How much impact will, you know, year-long testimony before the FCC really accomplish?

CRAWFORDWell, I'm hopeful that this giant merger will focus more Americans on what is a very basic social policy problem for the country. We are paying often five or six times as much as people in other countries pay for this bundle of services or for high-speed Internet access alone. We're supposed to be leading the rest of the world when it comes to our infrastructure. Our phone system was the envy of the world when it was introduced. But we're stuck in this weird situation where we're being driven into bundles by the pricing mechanisms used by the carriers.

CRAWFORDAnd yet we seem to have no options and no real oversight of the situation.

REHMBerin.

SZOKALook the concerns your caller has raised are really concerns about cable prices, which are ultimately reflective of the power of content owners. They're the ones that are getting more and more for their content. And that may be a good thing. We live in a golden age of television. I mean, shows like, you know, whether it's "The Wired" or "Game of Thrones," those are being funded by that revenue. So I'm not trying to demonize the content owners. But, if you want to talk about where the market power is, those are the people that really have it.

SZOKAWe have rules in place -- Susan doesn't think it's true, but it is -- to govern how those interactions take place. And if we...

REHMThe problem is we cannot choose the content.

SZOKAWell, so here's what I do. So I don't -- frankly, I don't care about a la carte on cable, I just want it on the Internet. And so where Susan's concern, I think, is most valid is, if we were talking about a situation where Netflix or some other Internet video service provider couldn't deliver service to me, right, I would be concerned about that. But that's not the situation here. The problems that Netflix has had are problems with the capacity that they need to pay for to be able to serve them.

REHMGautham.

NAGESHYes. Berin points out something that speaks to Susan's point, which is that U.S. does enjoy much more and a broader range of cable programming than any other country. It is fair to say, I think, that our cable television and video ecosystem, Hollywood, is the envy of the world. In many countries, they watch reruns of U.S. shows. So definitely the amount of money that's poured into cable has resulted in, I think, better offerings. On the other hand, sports are driving this. It's not -- as great as "Game of Thrones" and other shows are -- it is NFL football that is driving the increase in your cable bill.

NAGESHAt the end of the day, it comes down to ESPN, NBC, Fox and CBS all carry NFL football, all pay billions and billions of dollars to do it, and that is where the price increase is coming from.

REHMAnd passed on to consumers. Susan.

CRAWFORDWell, yes. The whole system is perfectly engineered to raise prices. So the very concentrated programming industry, and you're right about sports, it is the sledgehammer. And the very concentrated distribution industry both have it in their interest to keep the system arching up. Who gets squeezed is the consumer. And also new uses of these networks, not just for the programming that would serve the cable operators' interests, but for lots of high-capacity, uncontrolled uses for things like education and health.

CRAWFORDAnd that's where the power of these distribution networks, their very physical distribution power, gets to be a problem for the country.

REHMAll right. To Jason in Anderson, Ind. You're on the air.

JASONHi there, Diane.

REHMHi, Jason.

JASONLooking forward to you in 2016, honestly.

REHMGood.

JASONI think your panel has addressed this a little bit, but I understand the idea that we have to pay for the content on cable. Okay? I don't want cable TV. I just want my Internet. Okay? Why is my Internet bill going up at just about the same rates as my cable bill is going up?

REHMSusan.

JASONNow I should say as other people's cable bills are going up.

REHMSure. Okay.

CRAWFORDYeah, the quick answer here is because they can, because there is no competitive constraint. There is no reason to charge you any less. And, in fact, where I live, they charge you more for Internet access alone than they do for the bundle, because they want to keep people buying bundles because that's the source of the advantage against any competing infrastructure.

REHMSo you're telling me, if you cut out your bundle, you're not going to save any money?

CRAWFORDNo, I'll be paying more if I try to get just Internet access alone.

REHMGo ahead, Berin.

SZOKASo, first of all, it's not true that broadband prices are rising as fast as cable prices.

REHMBut that wasn't the issue.

SZOKAWell, I'll get to the issue.

REHMOkay.

SZOKASo consider what's actually happened. Comcast, for example, has raised speeds 12 times over the last 12 years. The cable industry just went through a massive transformation. They put $300 billion into the infrastructure. In the last few years, they've put into -- upgrading to what's called DOCSIS 3.0, to make cable work faster. And in markets where cable competes directly with FIOS, they are offering speeds of 300, 500 megabytes per second. There are very, very few takers for those now. But if prices are going up for broadband, it's because people are actually investing in the infrastructure.

REHMSusan.

CRAWFORDJust very quickly. We pay more per megabyte, when it comes to high-capacity packages, like anything 45 gigabytes and above, we pay more than any country other than Mexico, Turkey or Chile. And more and more Americans want these high-capacity connections. We're learning that we really, really like them. And it's -- we're just being gouged for those. It's not as a result of programming. It's just because they can charge more.

REHMAll right. To Carol in Brandon Township, Mich. You're on the air.

CAROLYes, that's Brandon Township. Yes, thank you, Diane. I love your show.

REHMThank you.

CAROLGod, I listen to it all the time. Thank heaven you're on the air.

REHMThanks.

CAROLAnyway, are you still there?

REHMYeah. Go right ahead.

CAROLOh. Okay. Okay. There had been some static. It disappeared. I thought maybe I lost...

REHMGo ahead.

CAROLOkay. According to what I heard on the "Tom Ashbrook Show" in the last couple of weeks is that Verizon just won, in one of the top two appellate courts in the land, to be able -- over the FCC -- they will now be able to package your Internet, so that you do not get anything you want on the Internet. You only get what your package offers you. And I'm sure Comcast is going for that in a big way themselves. Now, although I understand that the head of the FCC is very outraged that even -- that Verizon won and that they're pretty sure he's going to take it to the Supreme Court, but...

REHMAll right. Let's hear what our guests have to say, after I remind you, you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." Berin, go ahead.

SZOKASo this is, unfortunately, your caller has been the victim of sensationalism around this issue. The fact is the FCC didn't really lose. The D.C. Circuit tossed out two or the three rules in the open Internet order, but said that the FCC has broad power. They don't even need to make formal rules. They can just regulate on a case-by-case basis to deal with exactly these concerns. They can require that any deal struck be reasonable and nondiscriminatory. And Comcast is still subject to those rules anyway.

REHMSusan.

CRAWFORDBerin can speak more quickly. But let me tell you that what the D.C. Circuit did was say that the FCC can't deregulate with one hand, as it did 10 years ago, and then attempt to put regulations on these actors with the other. So it has vacated the nondiscrimination rules that the FCC tried to apply.

REHMGautham.

NAGESHThe court decision really opened the door for what we call a two-way market, where you could both charge consumers to bring them content, but then you could also charge content providers for some advantages in the delivery of the content. The FCC has said that they don't want this. And, to be honest, most ISPs have said that they're not interested in doing that with broadband. So we're going to see some action in this front. But, yes, there's definitely -- the caller is correct that this could change the business model for the way you get content over the Internet.

REHMWhere do you think all this is going, Berin?

SZOKAOh, I don't think it's going anywhere near the Chicken Little scenarios that people describe. The FCC, as I said, remains quite powerful in this area. They're still able to enforce the rules that were struck down against Comcast, because those were conditions of the NBC Universal merger. But what we're really talking about here is, as I said before, it's how you solve the net capacity problem. It's -- on the back end, for example, even Google Fiber, despite its gigabit speeds, still only streams at 3.6 megabits -- only slightly faster than cable systems, because the problem is really about capacity on the backend.

SZOKASo what the D.C. court decision actually means is that there is now the possibility of having a secondary market, except for Comcast, to negotiate for innovative arrangements on the backend to make sure that the services consumers want, like streaming, will work better. And the FCC can police those deals quite amply.

REHMGautham, where is all this going?

NAGESHWell, it's really going to -- the heard of the matter is that Comcast and the other people who provide broadband access, don't want to be in the business of owning a quote, unquote, "dumb pipe." They don't want to just be like a phone carrier and have very little control over their business model or what they can do. They want to be more like they are with broadband Internet, where you have a set-top box, you can buy movies, you can do all sorts of other things. And so they're looking for flexibility.

NAGESHWhether or not the government chooses to block this deal, they're going to ultimately have to make a decision about the role broadband Internet plays in our lives. And if they decide that it's something as vital as the Internet, then we're going to see greater regulation of it. That's just inevitable.

REHMSusan, where is all this going?

CRAWFORDWell, we've got a problem as a country. And our innovative stance with respect to the rest of the world is at risk. We don't have a cop on the beat for what has become basic infrastructure; that's a high-capacity information connection. It's a utility. It's subject to no real rules. And we're paying far too much for it. And the conflict of interest built in here with programming, gives the power of the cable companies to slice, dice, restrain and control this market.

REHMHow much will local jurisdictions have over what they get, Gautham?

NAGESHProbably not a lot, in truth. This is going to be something that -- you're going to get your local broadcast TV, but as we see consolidation in the cable market, aside from sports, content will become more nationalized. I think that is the broader trend.

REHMGautham Nagesh. He is a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Berin Szoka, President of TechFreedom. Susan Crawford, she's joined us from Cambridge where she is a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. Thank you all so much.

SZOKAThank you.

NAGESHThank you.

CRAWFORDThank you.

REHMAnd thanks for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.