Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

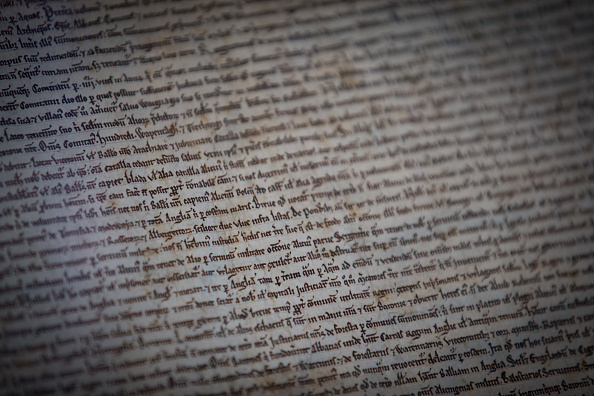

A copy of the Magna Carta on display in Salisbury Cathedral's Cloisters and Chapter House on Feb. 27, in Salisbury, England. To celebrate the 800th anniversary of the historic charter, the cathedral — which boasts to have the best-preserved Magna Carta of the four originals — opened a new interactive exhibition on the document, its creation and legacy.

In the 13th century a group of Englishmen met with their king in a meadow called Runnymede to negotiate the terms of an agreement. It was essentially a peace treaty between King John and rebellious barons who wanted an end to high taxes, arbitrary justice and perpetual foreign wars. The result was the Magna Carta. Today, 800 years later, the Magna Carta and the principles it contains are revered for giving birth to Western democracy. In a new book, historian Dan Jones brings the turbulent era alive and explains how this medieval document became legendary.

From MAGNA CARTA: THE BIRTH OF LIBERTY by Dan Jones, published on October 20, 2015 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Daniel Jones, 2015.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. This year marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. Issued by King John of England to quell a rebellion among the barons, it established that everyone was subject to law, even the king. The Magna Carta inspired our own founding fathers. Its principles are present in our Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

MS. DIANE REHMBestselling author, Dan Jones, talks to me about his new book titled Magna Carta, the birth of liberty. And, of course, he speaks with you as well. I hope you'll join the conversation by calling 800-433-8850. Send your email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. Dan Jones, it's so good to see you again.

MR. DAN JONESAlways a pleasure to be here.

REHMThank you. I know that many, many history buffs in the audience know that the words Magna Carta mean great charter, but tell us what it's all about.

JONESWell, the Magna Carta, as you say, it's a great charter and the easiest way to describe it in its origins is that it was a peace treaty between King John, the third Plantagenet king of England on the one side and a group of rebellious barons who went around under the rather marvelous name of the Army of God and the Holy Church. All rebels like to have a good grandiose name and they were no different.

JONESIn the spring and summer of 1215, John's barons rebelled against him and their grievances were many. In the first instance, John had been pursuing a very expensive war in the kingdom of France to win back lands he'd lost at the beginning of his reign very unsuccessfully. On the 27th of July, 1214, his allies had lost a huge battle, the battle of Bouvines and John has returned to England with his tail between his legs.

JONESHe was broke. His reputation as a military leader was totally bust.

REHMJust let me pause you there. How many barons are we talking about?

JONESWe're talking about a very small group of very rich and powerful people. Now, in Magna Carta itself, in the charter, it refers to 25 barons, a council of 25 who would hold John to account if he broke the charter's terms, which, as we'll probably discuss, he did. And they were part of a larger group of barons, but really we're not talking about many more than at most 200 men, very rich men.

JONESSo in its origins, when we think about Magna Carta, let's get away from the idea that this was something for everyone. This was an oligarch's charter with the head of the robber barons, if you like.

REHMAnd why did it become known as the Magna Carta?

JONESWell, in the early history of Magna Carta, when it was first granted, there was one charter or, you know, there was one agreement, 63 clauses. It was of the moment, of summer 1215. When it failed and when the civil war, which Magna Carta tried to prevent, had broken out, to solve the war once John died and his young son's government came in, the government of Henry III, they reissued Magna Carta.

JONESBut they reissued it alongside another charter, which is called the Charter of the Forest. And to distinguish between these two charters, one was called the Great Charter, one was called the Charter of the Forest. So the name Magna Carta is so grand and I think that's one of the reasons it's endured. It is a wonderful, big, bruising name.

REHMSo talk about what life was like before the Magna Carta came into being. You talked about fights. You talked about battles. You talked about losing battles. How were -- how powerful were those barons and what were they after?

JONESI think you have to see the barons as mini kings. That's certainly how they saw themselves.

REHMMini kings?

JONESHow they saw themselves. If we take a man like Robert Fitzwalter, who was leader of this army of God and the Holy Church, one of John's -- I mean, obviously acquainted with the king, Fitzwalter had become very rich trading wine through the city of London. He was a big landholder, particularly in East Anglia in the east of England. And we still have, which is actually marvelous, his seal dye, which he would've used to seal his documents, you know, a piece of metal with an image that was printed in wax.

JONESAnd it shows him as he would want to have been seen on horseback, sword in hand, chainmail, the coat of arms of one of his allies, Saer de Quincy, who he thought of as a brother in arms and also a dragon underneath the horse sort of cowering in fear at the sight of Fitzwalter himself. And that's how these guys saw themselves. They were like mini kings exercising control over large swaths of land, exercising influence and authority over large numbers of people. But above them, much, much richer, much, much wealthier, much more militarily resourced was the king himself. And it was these groups that were clashing.

REHMAnd what about the lords? What was the difference between the barons and the lords?

JONESWell, you know, you have actually a pretty well-graded or clearly delineated society. So king at the top, then the barons, then some sort of lesser barons and lords, less wealthy, less well resourced. Below them, a class of men who were knights. Now, that whole class of -- we're still basically talking about very rich men -- shared values of chivalry, you know, the sort of code of conduct, if you like, that was emerging or was peaking almost at the beginning of the 13th century.

JONESAnd one of the interesting things about John was that they saw John as not living up to the code of chivalry. He was untrustworthy. He was thought of as cowardly. He was said to have been made lecherous advances on the wives and daughters of his barons and he would snigger other people's misfortune. And it sounds prosaic, but laughing at other people's misfortune was a real violation of the code of chivalry and there was a feeling amongst John's subjects that he was not a chivalrous man. He was not really a prince.

REHMSo how did the barons manage to bring him to the point where he was willing to create with them the document that preceded the Magna Carta?

JONESWell, they rose in arms against John early in 1215. The literally gathered men to their flag and they marched against John. It was pretty unsuccessful until the barons struck a deal with the merchants, effectively in London. And during May, 1215, they -- on May 17th, on a Sunday morning when everyone was at church in London, they were allowed into the city and they took control of London.

JONESAnd then, as now, London really stood apart from everywhere else in England. It was the biggest, grandest, most important city. If you controlled London, you controlled access to the royal treasuries inside the Tower of London at Westminster. And once the barons took London, John was in trouble. He had to come to the negotiating table to buy himself some time, really, to raise an army of mercenaries from Europe with which he could take the fight back to his enemies.

JONESSo John's appearance at Runnymede, which is not far from London, it's about 25 miles up the River Thames from London, John's appearance at the negotiating table in Runnymede was not the act of a benevolent man who suddenly saw the wrong -- the error of his ways. He did it because he was forced to come to terms to buy himself some time.

REHMAnd what about the Church's role in all of this?

JONESWell, John had a very checkered relationship with the Church. If we look back to John's family, the Plantagenets, they were thought to be descended from the devil and, in fact, John's brother, Richard the Lionheart, was very proud of this. You know, he said, from the devil we came, to the devil we'll return. More specifically, midway through his reign, John had fallen out with the Church spectacularly, with the Pope Innocent III, great warrior, crusading pope, an exact contemporary of John's.

JONESHe's fallen out over the appointment of the Archbishop of Canterbury. John wanted one man. Canterbury wanted the other. The Pope imposed a third man. John refused to accept this and the Pope placed the church in England under interdict for more than five years. Now, interdict means no more church services. Church service -- totally suspended churches are shot and in a very religious society.

REHMOf London. Throughout London?

JONESNo, throughout the whole of England.

REHMOh, my god.

JONESSo imagine in a very, very religious society, even more religious than anywhere really in the West today, all church services are suspended. John, himself, was personally excommunicated. Now, he managed to reverse this position in 1213 because it looked like the Pope was going to sponsor an invasion of England and John had sort of flipped and brought the Pope back onside by saying he was going to go on crusade. He was so sorry, bladdy, bladdy, blah.

JONESSo at the time of Magna Carta, the Church was on John's side and the prime mediator at Runnymede was Archbishop Steven Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury over whom all this trouble had begun. And Langton, his sympathies lay with the rebels. He was a very scholarly man who'd had a brilliant career at the University of Paris and thought deeply about the religious justifications for power, about what it meant to be a prince.

JONESHis role at Runnymede was, and in months before, was to stand between the two parties and bring them to some sort of agreement, which he did, although that agreement didn't last for very long.

REHMAnd what basically were the barons saying they wanted?

JONESWell, if you read Magna Carta -- now, Magna Carta was written in heavily contracted Latin. It's obviously now translated into English. If you read through it -- I read the audio book for the new book and so to read it aloud is actually how Magna Carta was supposed to be transmitted. But it's an interesting process because there are so many demands that don't really fit logically together.

JONESYou start with freedom for the Church. Then, you move on very abruptly to inheritance tax is limited, a very low level for the richest people in society. You then move onto all sorts of what are now arcane and obsolete matters of feudal principle, how long a widow can stay in her house by law after her husband dies. There are really quite mundane things. How many fish traps are allowed in rivers, all sorts of things.

REHMDan Jones, his new book titled, "Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty." Short break. We'll be right back.

REHMDan Jones is here with me. You know him well as the author of "The Plantagenets" and "The Wars of the Roses." Now he's come out with a new book titled, "Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty" And we understand the National Archives has tweeted, after learning about Dan Jones' "The Birth of Liberty" on "The Diane Rehm Show" on NPR, check out the 1297 Magna Carta in person at the National Archives. And throughout our conversation, we'll get to that 1297 version. But just before the break, you were talking about what was in that earliest version and the extent to which it limited women and their ability even as widows to own people for more than a few days.

JONESWell, it's so interesting, isn't it? We think of the Magna Carta today as the starting point for democracy, liberty, rule -- ruled by law, all of which is true and you can find it there in Magna Carta. But there's another narrative which we don't talk about, which is the things that are in Magna Carta, which tell you exactly the opposite. It's kind of the most right-wing document in history in some respects. Total freedom from regulation for the Catholic church. Total freedom from oversight for the city of London, financial interests. Heavy restriction of women's rights, of the rights of Jews. A demand that all foreigners be kicked out of the country. You know, this is, in some ways, a really reactionary document…

REHMYeah.

JONES...if you wanted to play it that way. And I find that extremely interesting because we can often forget, when we think about the post-history of Magna Carta, its importance to us today. We can forget that actually what was at stake in 1215 was affecting a very, very narrow strip of society. And if you and I, Diane, had gone down to Runnymede in 1215 and said, democracy. Let's have rights for us all. They'd have probably chased us away with their swords.

REHMYeah.

JONESAnd, you know...

REHMYeah.

JONES...and we'd have run out of there as fast as we could.

REHMAnd the Magna Carta, as you said earlier, issued in 1215, did not last very long and did not stop civil war.

JONESWell, I said earlier that John had come to the negotiating table as a way of buying time. And I think that's -- that was made very clear almost immediately. Because having agreed to Magna Carta in the week beginning Monday, 15th June 1215, great ceremony where John's barons were reconciled to him, when he granted -- he didn't sign, by the way, he granted this charter. John then wrote to the pope, who by this stage was his ally, and said, my barons have forced me to agree to this charter. It demeans my royal authority. And the pope wrote back and said, what a load of nonsense. I annulate anyone who obeys Magna Carta will sort of burn in hell for all eternity.

JONESSo Magna Carta, by the end of August 1215, a matter of two months, had collapsed. And the civil war that it was designed to prevent began. And it was a truly vicious civil war, the sort of civil war that hadn't really been seen in England since the anarchy of Stephen and Matilda the previous century, you know. And it was at this point, really, that the effects of Magna Carta became obvious, I think, to the vast majority of people, who wouldn't have been at Runnymede, but they certainly would have known when John's armies of foreign mercenaries ran through their land burning their houses down and killing their families.

REHMHere's an email from Michael, who says, the Magna Carta has been described as a system by which a bunch of thugs, barons, distribute the wealth collected from the peasants. Is this narrative correct?

JONESI'm not sure I would go totally along with that. But I do see where it's coming from, in the sense that, as I've been saying, Magna Carta in 1215 was about the rights of barons. And it didn't pay any attention to people who weren't legally free, so that didn't include most peasants. And it didn't pay much attention to anyone who wasn't a rich man, if you like. So yeah, I would go along with the sense that, if you were a peasant in 1215, life before and life after the charter would have been more or less the same. Which is, you know, to borrow the Hobbesian phrase, nasty brutish and short.

REHMSo, King John dies. The Magna Carta is revived. How?

JONESThis is probably the great moment in the history of the Magna Carta. John died in the middle of a civil war of his own creation. He fell sick, probably from dysentery, apologized very belatedly for all the dreadful things he'd done, such as starving the wives and children of his barons to death and, you know, and so on and so forth. Sorry, sorry, sorry on his deathbed. And he died and everyone thought he went to hell. In fact, Matthew Paris said, foul as it is, hell itself is defiled by the presence of John.

JONESPut all that aside, once John was dead, you had a very difficult situation because, during the civil war, his baron enemies had invited a new candidate for king to come to England. It was Louis the Lion, son of the King of France. They'd invited him over and said, we've had enough of the Plantagenets. Let's have a new king. Louis, the crown is yours if you want to come and help us take it. So at the moment of John's death, there were effectively two rival kings -- rival candidates for kingship, John's son, 10 years old, Henry III and the adult, Louis of France.

JONESNow, you might say today, well, you've got an English king on one hand and a French on the other.

REHMExactly.

JONESDon't think about it in those terms. The English had been used to being invaded from France. Think about the Norman conquest in 1066. Think before that and it's not invaders from France, you'd had the Vikings, Saxons, whatever. At the moment of John's death, the idea of another king coming from France, I mean, it wouldn't have struck people as totally outrageous. So there was a big problem for the few remaining loyal men around John's son. And as a way of, I think, showing their commitment to a reformed system of government, they decided -- and this was brilliant -- they decided to revive Magna Carta...

REHMHmm.

JONES...to amend its terms somewhat, but to revive Magna Carta and to offer it as a platform for a new government. And they did that successfully. So in 1216 and 1217, Magna Carta was reissued as the foundation for a, if you like, a new monarchy. And it was spectacularly effective. And that was also a vitally important moment in the history of Magna Carta because it shifted from being a peace treaty imposed on an unwilling king to being something that was given, if you like, of the crown's own volition. It was offered to the people. And from that point on, every moment of serious political or constitutional crisis in the 13th century, Magna Carta was, if you like, dusted off and brought back as a means of reconciling (word?)

REHMBut how was it changed in the process from that, give everything here, restrict everything there?

JONESWell some of its terms were changed. So at the moment of its reissue, there were some very awkward terms, which didn't -- which had been -- so the terms that said foreign advisors must be removed from the king. Well, unfortunately, Henry III, the young King, had got a lot of foreign advisors...

REHMOf course, at 10 years old.

JONES...who didn't want to remove themselves. So they got rid of that clause. Most importantly, there was a clause in the Magna Carta of 1215 known as the security clause, right at the end, which said, if King John doesn't abide by these terms, then a counsel of 25 barons can distain and distress him and make war upon him, basically in any way they see fit, until he comes to the negotiating table. That was the key problem in Magna Carta. Because a peace treaty that was designed to stop a civil war had embedded in one of its longest clauses the mechanism for starting a civil war. So that was removed when Magna Carta was reissued because it was obvious that there were big problems with making war on a king in order to prevent a war. I mean, you -- it's a vicious circle, if you like.

JONESSo over the 13th century, the terms were revised, were sort of winnowed down or updated. Nevertheless, by the time you got to the end of the 13th century, when Magna Carta was still being reissued -- at this point by John's grandson, Edward I, Hammer of the Scots, Longshanks -- I'm sure you know him from "Braveheart" -- at this point, Magna Carta's terms were starting to become somewhat outmoded. And really, it was the idea of Magna Carta, it was the symbolism of Magna Carta, which stood for more than its terms.

REHMAll right. I want to open the phones, 800-433-8850. First, to Dixon in New Albany, Ind. You're on the air.

DIXONThank you very much, Diane. As a former teacher, I know one of the sayings that kept coming around was that those who don't study history are likely to relive it. And I know that with the testing that is required of our students today, especially as that testing rolls near, a lot of times history will take a back seat to math and language, which it seems like they would go hand in hand but they often don't.

DIXONSo I just want to express my gratitude for people like your guest, who spend the time to not only explore the history but then to help preserve it, really, by providing some format for those of us who unfortunately are in the position to either teach it or not teach it, so that we can then come to know it. And that's -- I'll take any comments off the air. But I really appreciate that. Thank you.

REHMAll right, Dixon. And I must say, I do too. Because what Dan Jones manages to do is bring excitement to that history, to bring it alive.

JONESThat's very kind. Thank you, Dixon, for those kind comments. Thank you, Diane, for yours as well. My aim in writing history is really simple, it's to make it as accessible to as many people as possible, whether you're nine years old or you're 90 years old. I want you to read these books, know that underpinning them is proper, serious, rigorous academic research. But they should read with the same sort of -- the same verve as a novel. You should get enjoyment from reading history. Because that's what I want. That's what I want from history.

REHMIt's interesting that the American Bar Association had a small monument built at Runnymede. So how has the Magna Carta affected the U.S. legal system?

JONESWell, a little earlier on, you read out the tweet from the U.S. National Archives here in D.C. It's funny, last time I was on the show -- this time last year -- I went from here to the National Archives in D.C. because there's a 1297 edition of Magna Carta, the one that was bought by David C. Rubenstein at auction for $20 million and is on loan to the nation. When you enter the National Archives in D.C. -- I'm sure a lot of your listeners will have, but if they haven't -- you go through security and the first thing you see, dimly lit, sort of there with great reverence, is this edition of Magna Carta.

JONESNow, when you progress up to the rotunda at the top of the National Archives, there you have the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights. Now this is almost a physical manifestation of the way, I think, that the Founding Fathers and that generations of Americans since have seen the Magna Carta. It is the sort of prototype, the starting point, the physical and metaphorical origin for the things that are great about the United States.

REHMSuch as?

JONESSuch as the Bill of -- such as the idea of equality before the law. Such as the idea that the government can't just lock you up because it feels like it. You know, these are the key clauses to knowing will we sell, deny or delay rights or justice. The idea of trial before your peers, these were fundamental ideas, as I -- I mean, I'm not a specialist on the origins of America, but it seems to me these were the fundamental ideas that the Founding Fathers were wrestling with.

REHMThat 1297 edition of the Magna Carta, what did it say about the rights of women?

JONESThe 1297 edition of Magna Carta is very similar in its terms to the 1215 edition. So I'm -- I don't think it was very much more enlightened than the 1215 edition. In fact, when we're looking at the 13th century, I'm sorry to say that we're not looking at a great time for the rights of women. There was some interest in widows' rights because, particularly in aristocratic politics, the genetics and the, you know, life meant that sometimes, you know, you had to deal with widows' inheritance.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." And we'll go back to the phones, to Roy in Rochester, N.Y. You're on the air.

ROYGood morning.

REHMHi.

ROYAbsolutely fascinating. I think you -- I think, Diane, went through what I wanted to ask. But in terms of that, I always like to look at a book and see its bibliography and its sourcing. Is there anything else you can tell us about your research? Did you look at, I don't know, Maitland, the charter rolls, or other materials that, you know?

JONESWell, when I was researching this book, what I wanted to do was place Magna Carta not only in its sort of broad, historical context, but actually directly in the context of the story of the year 1215. And one of the things that doesn't get looked at an awful lot are the administrative records that John's chancery was producing throughout 1215. In the beginning of the 13th century, there's a sort of explosion in recordkeeping, or at least in record preserving. And we have the most extraordinary minutia of John's life that's -- that have been left to us.

JONESSo we know when he's ordering 10 oak trees to be cut down in the forests of Essex to reinforce the Tower of London, because he knows the barons are coming and they're coming to London. He needs to make his castle secure. We also know that -- about John's obsession with hunting. He loved to hunt with birds. And he sends these detailed instructions to one of his -- the keepers of his birds in a castle in the Midlands, saying, okay, I want them fed on plump goat and occasionally on hare. And, you know, and he's always sending his dogs in one direction...

REHMHuh.

JONES...he's sending vats of wine in another direction.

REHMHuh.

JONESNow, this isn't the stuff of the Magna Carta. But it is the stuff of the world that produced Magna Carta. And when I was writing the book, I wanted to get this world in the round. There's a chapter in the book which I've devoted to the siege of Rochester Castle, which happened during the civil war. And usually that amounts to a line or two, maybe a paragraph in books about Magna Carta. I've given it a whole chapter because I want to show the consequences, practical consequences of the failure of Magna Carta, which was to bring about one of the most severe civil wars that had been seen in a generation.

JONESAnd this siege of Rochester Castle, which went on for six or seven weeks -- and John eventually, you'll like this, John eventually took Rochester Castle because he dug a mine -- not personally -- he had miners dig under one of the walls of Rochester Castle, prop up the mine with wooden struts, smear them in the fat of 40 pigs that he'd ordered, set fire to it -- so this thing burned, collapsed and took down one of the corners of the castle. So, as I say, this is not the stuff of dry, political and constitutional history. It is not directly of Magna Carta and its terms. But it is absolutely the consequence of Magna Carta for ordinary people.

REHMHow many people were engaged in that battle?

JONESAt Rochester Castle? Well, the sources differ somewhat, but they say 90 to 140 knights of the barons' side had gone into Rochester Castle and were holding it against the king. So we can probably double or maybe triple that as the number of people, because they would have had servants and attendants along with them. That was far too many people to be inside Rochester Castle because they hadn't had time to fully provision it with food. They'd rushed in there and then they got stuck in there. And very quickly they were reduced, as happened during most sieges, to eating their horses and eating whatever they could. Now think about -- have that in your mind, Diane.

REHMWow.

JONESWhile you're thinking about what it must have smelled like when John set fire to the pig fat in this mine, the smell of sort of roasting bacon when you're starving half to death. That -- that's, it's funny, that all sticks in my -- that stuck in my mind when I was writing that chapter.

REHMI can well understand. Dan Jones, his new book is titled "Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty." We'll take a short break here. More of your calls, comments, when we come back. Stay with us.

REHMAnd welcome back. Here's a comment on the DR Show website. I saw the copy that's at Salisbury Cathedral earlier this year. They claim it's the best preserved. It's both unassuming and massively impressive at the same time. What can you tell us?

JONESIt's very -- there are four original copies of Magna Carta that we know about from 1215. One of them is at Salisbury Cathedral. One of them belongs to Lincoln Cathedral and is on display at Lincoln Castle, and two are the British Library. And until February of this year, they'd never been together in all of 800 years, probably even at Runnymede. And I was incredibly privileged to be asked by the British Library to work with them on a project to unite them, them and Salisbury and Lincoln Cathedrals', to unite these charters for the first time. So for one day at the British Library they came together in this amazing display.

REHMWow.

JONESAnd I was asked to talk to the guests. There were 1,215 tickets allocated to people via a ballot. I spoke to the guests as they came in. Now to see the charters next to one another was quite extraordinary because they are -- you think, wow, they're all just bits of vellum with old writing on it. They're not. They're very, very different. For a start, they're differently shaped. And you think, well, why would that be. Well, because parchment or vellum is made from an animal skin, and its shape depends on the shape of the animal itself. So they're different shapes.

JONESTheir -- the text is arranged somewhat differently. In the case of the Salisbury copy, it's written in a completely different style of hand. So of the other three, it's in what's called chancery hand, the typical handwriting used by officials of the royal bureaucracy. But the Salisbury edition is in a completely different type of handwriting. It's called book hand, and it's much more something you'd see in a Psalter or a prayer book from the period.

JONESAnd that, you might say, oh, well, that's sort of very interesting, Dan, but actually that's important because it tells us that in 1215, the Royal Chancery was working so hard to produce copies of this thing they evidently had to draft in other writers, and they drafted in writers who were not expert, necessarily, in chancery documents. So when you look at the Salisbury edition, which is very, very beautiful, as well as unassuming, it is completely different from the others and fascinating.

REHMAnd last week there was supposed to be a display of one of these documents at the university in Beijing. What happened?

JONESWell, as far as I understand it, the copy of Magna Carta dating from 1217, one of the copies issued on behalf of Henry III, was supposed to go on display at the University of Beijing. It belongs to Hereford Cathedral. It's on loan. As I understand it, this copy has been kept inside the ambassador's house in Beijing rather than going on public display. Now that's kind of interesting because why on Earth would the Chinese authorities, who we think have basically blocked the display of a copy of Magna Carta, why on Earth would they be worried about an old piece of parchment in condensed Latin that most people aren't going to be able to read?

JONESWell, that tells you something very important about Magna Carta in general. The document itself is one thing. The legacy, the -- its existence as a symbol for equality before the law, for liberty, for human rights and democracy, even though those aren't written in the charter, it's there, and this old piece of parchment stands for those ideas. In London today, President Xi of China is being feted by the royal family and by Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne. And yet over in China, one of our Magna Cartas is tucked away in an ambassador's house for fear that it might incite dangerous ideas in Chinese students.

REHMInteresting, and here is a tweet. What kind of person was Richard the Lionheart?

JONESWell, Diane, I don't think we'd have wanted Richard the Lionheart sitting around the table with us in the studio today. Richard the Lionheart was John's elder brother. He'd been king before John, and I think we'd probably know him best for going and fighting in the Third Crusade, fighting the armies of Saladin in the Third Crusade in the Middle East. Richard was the man who boasted that the Plantagenets were from the devil and that they were diabolical. Richard himself was fairly diabolical we think. He certainly massacred thousands of people out when he was fighting in the Middle East.

JONESHe was, however, an extraordinary soldier, an extraordinary soldier in a way that John could never be and incredibly tenacious. When he was imprisoned on his way back from the Third Crusade, he sat in prison for more than a year when he -- while his brother John, then the prince, signed away half of his empire to the French king. When Richard got out of jail, the French king said to John, look to yourself, the devil is loose. They knew Richard was coming back. He came back. He made a quick stop to England, and then he spent the rest of his life fighting in France, and he won back basically his entire empire before he was killed in the South of France in 1199 because a crossbow bolt hit him in the shoulder, and the wound went infected.

JONESAlmost immediately, and certainly within five years, John had lost almost everything that Richard had gained back. And that -- that tells you about the disparity between the two of them as military men, as leaders.

REHMInteresting. And to Tahid in Tampa, Florida, you're on the air.

TAHIDYes, my question, good day to you both, my question is, was the Magna Carta totally put together autonomously? And you just spoke about Richard the Lionheart. I wanted to know what outside influences may have affected the coming together of the document as far as, you know, Middle East, North Africa or even east of the Rhine.

JONESSo the influences on -- that's a -- thank, Tahid, for that question. The influences on Magna Carta I think mostly come from a sort of English, Anglo-French tradition. I said earlier that one -- the main mediator was Archbishop Langton. Now Langton had had this brilliant career as a theologian at the University of Paris, where he'd been considering scholastic ideas about what the duties of a prince were, at what point it was permissible to rise up against your divinely anointed king if he wasn't performing his role correctly.

JONESLangton had been wrestling with those ideas, and he thought very carefully about them. Now in 1214, in the October, in the autumn of 1214, when the barons were starting to foment revolt against John, it's -- it seems likely that Langton was saying to them that there were certain precedents by which they might come up with a charter to restrain the king, one of them being, for example -- excuse me -- the Coronation Charter of Henry I, who had ruled England in the early 12th century.

JONESNow kings when they came to the throne in Norman times and early Plantagenet times, if they came to the throne in contested circumstances, might, as Henry I did, offer up a charter by which they stated some of the basic, fundamental governing principles of what they intended to do as king. Whether they really did intent do it -- well, they said they were going to do as king.

JONESNow the Coronation Charter of Henry I, for example, is much shorter and somewhat more vague than Magna Carta, but certainly there was this idea that some mechanism based on this sort of charter might be brought to bear on John.

REHMAnd of course many are asking this same question, from David in Webster Grove, Missouri. You're on the air.

DAVIDOh, thank you, Diane. I -- as a matter of fact, your guest still hasn't said the words social contract yet, but yeah, that was the basic idea, that we the people are paying taxes to some guy that claims that God put him in charge, you know, these kings ran around claiming that God put them in charge, and they were never fixing the bridges, they were never providing any services. They were just taking the money and claiming that they knew how to run our lives. But they would never do anything of advantage to us.

DAVIDSo the social contract, whether the merchants were able to strong-arm the social contract out of these crazy kings, or whether it was the other aristocrats who had territories to handle, but they still had to go out there and collect these taxes for those kings. So I've noticed with the USA Patriot Act in post-9/11 world that many of these aspects of our lives are being yanked away from us and sneakily by claiming it's too expensive for we the taxpayers to have a safe and calm world, that we have to buy the X -- underwear X-ray machines, and we have to allow snooping on our lives, and we have to allow border fences that a million dollars a foot.

DAVIDSo I think the same conditions are still in existence, that the crazy kings have busted the budget, and now the people have to decide how they're going to get their money and their social contract back.

JONESThank you, David. I think King John would have rather liked underwear X-ray machine. But I take your point. You know, these are timeless questions. How -- what is the social contract? How does it operate? How do you bring your government to justice when the government is also the enforcer of justice? And these questions were wrestled with in just the same way in 1215 as we are wrestling with them today. The conditions of the world may have changed, the technology has changed, the geographical outlook has changed, the religious mentality has changed, but fundamentally aren't we now asking the same questions that were being asked in 1215.

JONESWhat happens when the government abandons, or semi-abandons at any rate, its duty to the people? And how on Earth do you bring a government to account? And it wasn't fully answered in 1215, although the Magna Carta was certainly a brave attempt to do that. Will it be fully answered today? I think probably not because we live in an imperfect and incomplete world. But do we see in Magna Carta a model for what you might be able to do? Yes, we absolutely do. And that is why the Magna Carta has proven so enduring over 800 years.

REHMAnd Dan Jones is the author of a new book titled "Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty." And you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show. I want to shift subjects for a moment. I understand that you recently spoke with Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of Britain's Labour Party. Tell us about him and the upset election.

JONESWell, you're right, I met Jeremy Corbyn on a radio show in the U.K., which is on BBC called "Any Questions." And we were on a panel together. And actually I talked about the Magna Carta with Jeremy Corbyn. We sat in the green room beforehand, and Jeremy knew that I was a historian. I -- at this point he was still trying to gain election as the leader of the Labour Party. And I found him a very interesting, very interested, very passionate, very committed man.

JONESWe had a really, really interesting question -- conversation about the sort of -- an alternative radical history of the Magna Carta and things I've said to you about do we necessarily see the Magna Carta as an object of liberty, of democracy, or was it actually put together with much more conservative, aristocratic aims. He -- very interested in history. Jeremy said his parents had written a sort of radical history of the village that he grew up in, Shropshire.

JONESAs a politician, as a leader of the Labour Party, I'm not sure how much -- how long it can go on because I think Jeremy has a very committed, passionate, vocal particularly on social media support base. I think he's absolutely honest about what he wants to do. I think it's unrealistic. And there was a great line by a political commentator called Phil Collins who writes for the Times of London, who wrote during the election campaign. Phil Collins was Tony Blair's speechwriter for a while. So he's on the opposite side of the Labour Party.

JONESBut he said Jeremy Corbyn is a good man whose goodness will resemble oddness when placed in a harsh light, and I'm afraid that will probably be the case. He's going to come -- the absolutely hostility of the parliamentary Labour Party in the main towards his leadership. He has -- he's going to run into the contradictions of his own position, which were fine when you were back-bench rebel MP, which are not going to be fine when you're seeking election as prime minister of Great Britain.

JONESSo I think it's a very interesting project that's probably doomed to fail. But I thought he's a lovely man.

REHMFinal question. How did the Magna Carta influence the writing of the U.S. Constitution?

JONESI think you can find echoes in the U.S. Constitution and in the Bill of Rights of the language of Magna Carta, particularly clauses to do with the right to trial before your peers, about the rights of the -- of government officials to take your property. But I think -- you know, and I think in the time, Revolutionary American times, there was a sense that the Magna Carta was important. It was there on state seals. But I think it is more as a model and as an idea than as a sort of -- something that was sat down and copied out and turned into the documents that form the basis of America.

REHMBut do you think our founding fathers looked at it, studied it, read it before they began drafting?

JONESYes, I absolutely do. I think Magna Carta was on their minds. It had been on the minds of revolutionaries in the sort of -- the British and colonial world since the beginning of the 17th century, when the great juror Coke had -- jurist Coke had found in Magna Carta some model for opposition to the Stuart kings, you know. And so this sense that Magna Carta was a sort of year zero in the battle for liberty, in the struggle to make governments answerable to the people was -- was firmly around and in the founding fathers' minds.

REHMAnd you believe that they were happy to include some element of religion into the Constitution but to make sure that it was kept separate.

JONESYes, I think that's -- I mean, I think we're still dealing with a religious world, but I think the difference -- and as I say, I mean, I'm not a specialist on the American Constitution, but what I would say is that the difference between the documents that created America and Magna Carta is that there was -- you're starting to see a separation of the religious realm from the political and from the secular.

REHMRight.

JONESWhich if you go back to the 13th century, it -- you can't box -- you can't compartmentalize these ideas. The notion that there was sort of -- there's religion over here, and there's the rest of the world there didn't -- wouldn't have made any sense in the 13th century because the religious and the spiritual in the Middle Ages were manifest in the real world.

JONESYou look at maps from the Middle Ages, maps are centered around Jerusalem, and they include places like the Garden of Eden on them. It's -- they are manifest in the real world.

REHMDan Jones, his new book is titled "Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty." Congratulations. Thank you so much.

JONESThank you, Diane, always a pleasure.

REHMThank you, and thanks for listening, all. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.