Diane’s farewell message

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

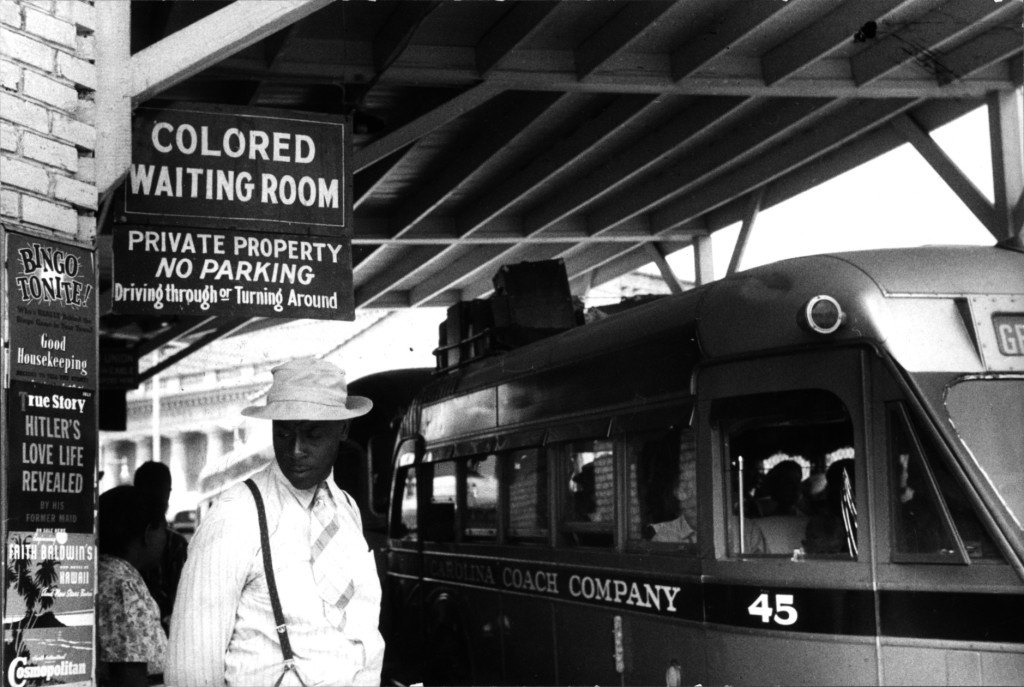

Bus station in Durham, North Carolina in 1940.

Historian Charles Dew was born in 1937 and grew up in St. Petersburg, Florida. His parents, along with every white person he knew, believed without question in the inherent inferiority of black Americans and in the need for segregation. In a new memoir, “The Making of a Racist,” he describes what he learned as a child and how he gradually overthrew those beliefs. Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Isabel Wilkerson details the crushing realities of the Jim Crow South from the other side of the color line. In her 2010 book, “The Warmth of Other Suns,” she documents the migration of black families in the 1930s, 40s and 50s in search of better lives in the North and in the West. Charles Dew and Isabel Wilkerson join us to talk about racism in American, then and now.

LISTEN: Diane Rehm And Isabel Wilkerson Remember Roosevelt High Over The Years

The cupola that rises above Roosevelt High School seems to draw the eye to the decades-old building - not only is it higher than most of the structures around it, but the school was built on a slight incline as 13th Street climbs from Upshur Street to Allison Street, giving the sensation that it's meant to serve as something of a focal point of the neighborhood it's in, Petworth.

MS. DIANE REHMThanks for joining us. I'm Diane Rehm. In her 2010 Pulitzer Prizewinning book titled "The Warmth of Other Suns," writer Isabel Wilkerson details the struggles of several black families who uproot their lives to escape from the Jim Crow South. Historian Charles Dew, born in 1937 grew up on the other side of that color line where privilege was a given. His new memoir is titled "The Making of a Racist." Both Isabel Wilkerson and Charles Dew join me to talk about life in the segregated South and the challenges we face today.

MS. DIANE REHMI'm sure many of you will want to join us. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Send your email to drshow@wamu.org. Follow us on Facebook or send us a tweet. I'm so glad to have you both with me.

MR. CHARLES B. DEWThank you, Diane. Wonderful.

MS. ISABEL WILKERSONGreat to be here.

REHMSo good to see you. Charles Dew, I know you've written two other books that focused on American history and racism, but this book, "The Making of a Racist" is quite personal. Talk about your own history.

DEWI was trained as a historian in the sort of formal sense that Johns Hopkins University, where I went, trained historians. We were told to keep ourselves out of the history. We were social scientists. We weren't to involve ourselves in our history. But I've been teaching the history of the South for a long time and I found myself going back to my own stories frequently to make points to my students. And when I did, I had their attention. Student attention can wander at times.

DEWAnd whenever I started talking about myself, being on the white side of the color line in the Jim Crow South, the students were really riveted and frequently, they came by my office to talk. And as I was thinking about what I wanted to do at this stage of my career, I'm getting a little long in the tooth, I kept coming back to these stories and I thought, maybe there's something here that I can say that will be helpful, that it will help people understand how this toxic racism gets transmitted from one generation to the next.

REHMYou, as a youngster, believed that you were on the right side of history and believed, as your family did, that blacks needed to be segregated from whites, that they were inferior, that you could look down on them.

DEWAbsolutely, absolutely. White supremacy reigned and the other side of white supremacy is black inferiority. We were taught, as reasonably well bred white Southerners, to behave decently, but the whole racial etiquette that governed the way black and white interacted with each other, all of those customs and folk ways that were part of the Jim Crow South I absorbed. And the word I use in the book is osmosis. A lot of it, you didn't have to be told. You just looked as a child growing up.

DEWThere were cups and saucers in the cupboard that were for the two people who -- African Americans who worked at our home. We were not to use those. We were told that very early. If an African American person came to any door of our home other than the back door, there was a potential explosion in the offing. I witnessed my father do this once. It was a searing experience. I never forgot. So you just absorb this stuff and you're told over and over again, this is best for both races.

DEWThey're happy on their side of town. We're happy on ours. It's the way things were meant to be.

REHMAnd then, you went to boarding school in Virginia.

DEWI did.

REHMAnd what was that like?

DEWMore of the same. A better education than I could've gotten at home, but my school in Virginia was really an extension of the Jim Crow culture in the South that I grew up in. Some of the things I learned there included racist jokes. Almost all of our humor was based on crude, racial stereotypes. The jokes we told each other were just reinforcing that whole notion of we're better than they are.

REHMAnd in your circle, whites never questioned that whole issue of segregation and racial separation.

DEWAbsolutely correct. It was not questioned. It wasn't challenged. And you learned early on that it wasn't to be challenged.

REHMOf course, these were Southern laws, but the whole country...

DEWAbsolutely.

REHM...was part of that.

DEWAbsolutely. Racism did not stop at the Mason-Dixon Line. It extended north as well and that was pretty clear to me as I traveled back and forth across. I'd never been north of Washington when I went to college so my New England college experience was really critical for me.

REHMIsabel Wilkerson, you looked at the horrific consequences of the Jim Crow laws from the other side. Talk about that.

WILKERSONWell, what he's describing is the other side of what was ultimately a caste system. You know, we don't think of caste in our country. We think of, perhaps, India or Victorian England. But a caste system is really an artificial hierarchy in which, in this case in the South, everything that you could and could not do was based upon what you looked like. And in order to justify the inequality that was built into the system, it meant that there had to be a reinforcement of the presumed superiority of one group over the other.

WILKERSONAnd, you know, this book that he's written is this outpouring of his family and, you know, childhood experiences isn't -- you know, it gives us a window into how that's reinforced over the generations.

REHMAnd in your book, you spanned the 20th century talking about those Jim Crow laws affected people, looking at conditions in the South and the great migration. Six million people involved. Talk about that.

WILKERSONYeah. So the caste system that I'm describing is actually the South as we know it. The South at that time was essentially an authoritarian totalitarian regime, language that we don't often think of in our country. And every aspect of a person's life was strictly controlled formally and by custom, every single thing that you could do. So it was actually against the law for black people and white people to so much as play checkers together. There were separate Bibles in the courtrooms throughout the South.

WILKERSONThe smallest thing that could be segregated was planned and thought out.

REHMYou're saying that in the courtroom...

WILKERSONIn the courtroom.

REHM...a black could not put his or her hand on the same Bible?

WILKERSONThe very word of God was segregated in the Jim Crow South.

REHMExtraordinary.

WILKERSONThere was a sense of the need to separate, at every possible turn, so there could not be wider possibilities for people to get to know one another for any possible equality. It needed to be driven home at every aspect of one's life on both sides.

REHMAnd for you, Charles, day to day life, when you were growing up in St. Petersburg, Florida, you talked about the separate cups and saucers. There were even separate bathrooms.

DEWCorrect, correct. There was a half bath off our back porch that was very poorly appointed. That was for Illinois, the woman who served us for years as a maid and someone who did some cooking and cleaned our house and did the laundry. And we had a yard man. They were to use that...

REHMBack door.

DEW...back door. I'd said in the book, it could've said "colored" over it. It didn't. But that's essentially what it was. Those were the signs that were ubiquitous all over the South, "white" and "colored". We had a nice tile bathroom on the second floor that we were to use. We were not to use theirs. They were not to use ours. I mean, it was that rigid.

REHMAnd had you ever shaken the hand of a black person?

DEWNot until I was 17 years old and went to college. It wasn't done. It was one of those segregation customs that was rigidly enforced. You didn't refer to grown men and women by Mister or Miss or Missus. You used first names. There were a whole series of Jim Crow mannerisms and speech patterns that we were expected to follow. And, again, you just absorbed it.

REHMAnd what about black children of the era, Isabel? What were they taught?

WILKERSONThey were taught to fear, to fear stepping out of their place. It was drummed into young people that their very lives depended upon being on their side of that wall that was an invisible wall because any little thing that you could do could mean your life. And so there's so many examples of young people who were, if they walked on the wrong side of the street or if they walked into an ice -- one -- a young man in the book, he went to get some ice cream and he was -- he had to wait and to wait and to wait.

WILKERSONAll of the white people would come in and they could go in front of him. And in this particular case, the owner of the shop decided to play a very cruel trick on him.

REHMI want to hear about that after we take a short break. We will be welcoming your calls, your comments. Stay with us.

REHMAnd welcome back. Charles Dew is professor of history at Williams College. He's the author of a new book. It's titled "The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History and the Slave Trade." Isabel Wilkerson is here. She's a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of the bestselling 2010 book "The Warmth of Other Suns." And Isabel, you were telling a story about a young black boy who walked into an ice cream store, had to watch and wait as a stream of white children were served, and then the owner decides to play a trick on him.

WILKERSONA very cruel trick. We should set this up by saying this is in Florida, the very state where Charles grew up, and this was one of the people in this book that I'd written, and his name was George Starling, and he was a little boy. He went in to get ice cream, as children want, and the other children could go ahead, and grown people, too, could get ahead of him, and he was waiting.

WILKERSONAnd then finally the store owner was there with one of his friends, and the store owner had a little dog, it was a fox terrier, and he had trained the fox terrier tricks in the same way that we're speaking about the -- how the Jim Crow laws and customs just infiltrated every aspect of life. And so he -- with George there as a little boy at the counter, waiting to get his ice cream, the owner calls up the dog to the counter, puts the dog on the counter, and he says to the dog, would you rather be an N or die.

WILKERSONAnd so the dog flips over onto its back, shakes its legs and then, you know, and then flops over. And this is the message to this little boy about the cruelty of the caste system, the cruelty of this hierarchy based upon what you look like and that you can be humiliated at any turn, at any moment, and that this was -- this was a fun joke of -- the owner just chortles with laughter with his friend.

REHMCharles, I'm sure you perhaps might have been one of those white children going ahead of blacks in line at an ice cream store.

DEWEasily, and I would have thought nothing of it. It never would have occurred to me that this person was there before I and should have been served. It just wasn't in our -- in our sort of realm of thinking. That's what's so surprising, the degree to which all of these customs and folkways were taken for granted and unquestioned by whites. It was just the way things were meant to be.

REHMSo how -- I think there is a question in your book, and you ask, or someone asks you, why do grownups put such hate into their children.

DEWThat was one of the most powerful moments I experienced growing up. I had gone to Williams College, I had gotten out of the South. I was beginning to question, really for the first time, a lot of what I had grown up with. And I used to give Illinois, Illinois Browning Culver, the woman to whom my book is dedicated, I would give her a ride home, and I wanted to talk to her. I had -- I had questions. I had -- I was starting to doubt a lot of the things I believed in and grown up with.

DEWAnd we in those rides to her home entered into a series of conversations that broke through that Jim Crow ice or whatever you want to call it.

REHMGive me an example of the conversations.

DEWWell, it started by my asking her about her son. They had one boy, Roosevelt, who had left the South, I knew that, and I asked her about him and where he was and what he was doing, and she told me. And I broke the ice, and I said Illinois, it's just a shame that folks have to leave her to get an equal shake.

REHMTo go North.

DEWTo go North, and I saw her look at me. She glanced at me, and this was -- this was dangerous territory. So I went on to say it just shouldn't be that because of somebody's race they're treated the way they are. And that broke the ice for us, and we started talking, and she told me a lot about what she had to go through. Just an example, the department stores downtown would let her buy a dress, but they wouldn't let her try it on. There was one.

DEWMy uncle had a furniture store in that building, which made me proud. There were no black guests on any of the television talk shows except for one, Bill Cullen, and she would time her cleaning schedule in our home so that she would be in the living room, we had the one television, so she could turn on Bill Cullen and watch that show. And I just remarked one day, I said Illinois, you seem to love that show. She said that's the only show that has colored folks on as guests. I never knew that. And she was put through this kind of humiliation on a daily basis.

DEWOne day she said something that never, ever escaped me. She said, Charles, why do the grownups put so much hate in the children. And she put her finger right on it, that that racism, that white supremacy, was passed from one generation to the next among white Southerners with all the certainty of a genetic trait.

REHMAnd that's where I must ask you, as you found yourself changing, how did your parents feel about your relationship with Illinois?

DEWI didn't tell them that I was having these conversations with them. The blowup occurred with my father, who was very firm in his convictions on white supremacy. By the time I was a senior in college, I was questioning so much of what I had grown up with, and my father was a very good lawyer, but the Brown decision, the...

REHMBrown v. Board.

DEWV. Board just stuck in his craw. He never could get tired of chewing on that bone. And he was doing this at dinner one night, and I just blew up. I said pop, the 14th Amendment covers that, you're wrong. I think I know more about constitutional history than you do. And he went silent. And when I got back to college, my mother phoned me. This was an era when long distance calls were expensive.

REHMOf course.

DEWAnd you didn't -- you didn't make many of them. She phoned me, and she said, you've got to apologize to your father. And I sat down and thought long and hard, do I want to do this, or do I want to stick to my guns. I was 21 years old. I knew that it would be an irreparable breach if I persisted, and I decided I had to call, and I did.

DEWWhat that meant in the future was all of this material was off-limits for us.

REHMWow.

DEWWe spent most of our time talking about football or things Southern males talk about.

REHMChanged the relationship rather completely.

DEWIt did. It meant that this was off-limits, and he knew how I felt, I knew how he felt, and we just decided that we would love each other without going there.

REHMInteresting. Isabel, you and I happened to attend the same high school here in Washington, D.C., Roosevelt High School, and you have on the colors of the Rough Riders today. I hope those people listening around the country and around this area will recognize that. I, however, graduated in 1954, the year of Brown v. Board. So I never once attended school with a black person. You, however, much, much younger than I, saw a different Roosevelt High School, totally integrated. Tell me about your life here in Washington.

WILKERSONWell, it -- by the time that I got there, it was 100 percent African-American. The switchover, which was the result of the great migration to the cities to the North, the Midwest and West, the people like the sons of Illinois, my parents were among those people who migrated, the six million people. And the response in the North was one of redlining and restrictive covenants and resistance and hostility to the arrival of these people who were escaping these almost unimaginable circumstances in the South.

WILKERSONAnd so by the time -- and it was not very long before, you know, by the 1970s, the school was almost -- was predominately black, almost completely black, and this was a complete switch and turnabout as a result of the resistance, the fear and the hostilities that met people here in the North.

REHMSo you see when I was here in school, Cardoza was completely African-American, Roosevelt completely white, and then we were told that after that 1954 decision, there would be a few black students from Cardoza integrated with those at Roosevelt. It sure didn't happen all at once.

WILKERSONI think that what we're still dealing with as a country is the attempt to understand what is it -- first of all what the history is. It's -- we're only coming to an understanding. More people need to tell their stories, to understand how it is that we got to where we are. We need to recognize that we all have been exposed to really toxins in the way that we view one another.

REHMAbsolutely.

WILKERSONIt's in the DNA of how we interact. It's in the DNA of the systems and the hierarchies that exist to this day.

REHMAll right, I want to open the phones. We have a number of people waiting. First let's go to Birmingham, Alabama, and to Tamarin, you're on the air.

TAMARINHi Diane, I wanted to thank your guest for their courage to discuss this topic. It's very emotional, especially for those of us in the South. I'm a 50-year-old white woman. I was raised in the desegregated South, after Brown v. Board. So I was able to counteract my father's racist ways by going to school every day, and it was really wonderful. We had an experience in my life, though, here in Alabama, I've learned over the past couple years as a criminal justice person who reads the law and reads the different statutes that embedded still in our laws in Alabama, 1901 Constitution, for example, and landlord-tenant laws, for example, we still have racism built into our laws and into our ways.

TAMARINAnd we still have an older generation who still clings. I'm kind of curious if Dr. Dew has any insights into how we could go about trying to change the laws in Alabama, and I'm not talking about criminal justice system, I'm talking about landlord-tenant law, business relationship law, all those structured laws are built in terms of the landlord, the whites, have the power, the tenants, the blacks, usually the blacks, don't have the power. And if we can't even overcome that, I'm -- I just wanted to get some insight from Dr. Dew and your other guests on that.

REHMThank you.

DEWThat's a really good question. Brian Stevenson at the Equal Justice Initiative has written an eloquent book called "Just Mercy" about just how poisonous the law is for many African-American defendants. And I think supporting him and his work, supporting political candidates, if they come forward, who are willing to make change, who are willing to acknowledge these things that shouldn't be, the political system is a great instrument if people will register and vote and make their voices heard.

DEWBut it's hard. It's hard when you have been oppressed to not keep your head down. And I think it takes a lot of courage. It took so much courage for the people that Isabel Wilkerson talks about to leave the South. I think the same kind of courage is needed today. Things are still not where they need to be.

REHMExactly, and you're listening to the Diane Rehm Show. And today we have a report from the Justice Department regarding the Baltimore police and the manner in which they have disproportionately targeted African-Americans for stops and arrests. I mean, we've heard about this in various cities all over the country. One wonders how does it finally reach the level of the departments of police so that they, too, can understand their own inherent racism, Isabel?

WILKERSONI think it is necessary, particularly in this moment, to recognize the degree to which all of us have been exposed to these unconscious biases, which are built into our country and into our culture. And no one is immune, and it's an ongoing effort. Charles speaks about this as being a disease, and it is a disease, and there's really in some ways no recovering from it. There's always vigilance that's required because we've all been exposed to the unconscious biases that are built into our country.

WILKERSONI believe that what we -- what I am calling for is a radical empathy because I think that what's so missing from our society is recognizing when you see these videos of someone, say Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge or of Philando Castile in Minnesota, and you see these people who were really permitted to die in front of us on these videos, unimaginable for us to be exposed to this in 2016.

WILKERSONAnd this is still viewed as this is the way it has to be. There's something very wrong with that picture, and I believe it calls for radical empathy. We need to each see ourselves in these people and to recognize that the violence that this -- that these -- that this caste system, these inequalities, permit endangers us all.

REHMWould you agree?

DEWI couldn't agree more. The challenge is to walk in someone else's shoes who is very different from you and extend that sort of empathy and understanding to realize what their lives would be like.

REHMHow long did it take you, Charles Dew, to make that transition?

DEWIt happened when I was in college in New England, and it was a very slow and almost torturous process, one step forward, two steps back, one step forward.

REHMGive me an example.

DEWWell, I had an African-American classmate in my freshman dorm, and I was telling a racist joke to some of my classmates.

REHMWhite classmates.

DEWMy white classmates, and he walked by outside, and I stopped and froze.

REHMWow.

DEWBecause I had been taught never to humiliate anyone, but at the same time I was telling this joke that I had grown up with, and I thought I wonder if he heard. That was really the first time I had ever been in a position to wonder how someone who was African-American would react to something I was saying because this elaborate racial etiquette that governed the way white and black interacted had been in place the whole time I grew up.

REHMDid he hear you, and did he ever say anything to you?

DEWI approached him several days later and introduced myself, and he gave no evidence that he had heard, and we became friends. We -- he was the first person I had an open conversation with across the color line in which that conversation was not rigidly controlled.

REHMCharles Dew is professor of American history at Williams College and the author of "The Making of a Racist." And we'll take a short break here, more of your calls, comments when we come back. Stay with us.

REHMIsabel Wilkerson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. She's author of the bestselling 2010 book, "The Warmth of Other Suns." We have an email from Linda in Texas. She says, "It's important to say these things happened to people not now alive by people not now alive. Listen, learn, move on. Laws do punish these injustices if they continue." Do you believe that, Isabel?

WILKERSONI'm not clear on all that she's saying. I can only say that we have not recovered from all that we've been through. Partly because we do not know all that we've been through. We don't know our history fully. When you look at the photographs from the 1960s of -- and from 1958 and '57, from Arkansas, Little Rock, and the hate and the anger in the eyes of the people who were protesting and resisting the changes that were coming, many of those people are still alive. This is not something that is in the past. This is something that we're living with the consequences of even to this day.

REHMWhere were you born?

WILKERSONHere in Washington.

REHMAnd how long did you live here?

WILKERSONI lived here for the first 20-some years of my life.

REHMAnd how did you grow up?

WILKERSONI grew up raised by two people who had defected from the Jim Crow South. And raised me with the hopes and dreams that this would be an opportunity for me to have something that they could never have had. The idea of just walking into a library, Petworth Library, for example…

REHMExactly.

WILKERSON…they couldn't walk into a library. It was against the law for African-Americans to go into a library throughout the South. They never had that opportunity. One of the first things that they did was they took me to the Petworth Library when I was five years old and got me a library card. That's the hope and the dreams and the optimism that they carried with them even though they had been so repressed in the places that they had fled.

REHMHow did people, during those Jim Crow laws in the South, how did they obtain work?

WILKERSONWhile they were in the South or when they came here?

REHMWhen they were in the South.

WILKERSONThe caste system, which is why it's -- I call it a caste system and also our anthropologists of the era called it that -- meant that as in India or other parts of the world, there were specific things that you could do if you were black. There were only certain things that you could do. You could be a domestic. You could be a yard boy. You could only do the work that no one else wanted to do. Of course, many of them were sharecroppers and working the field.

WILKERSONOr they were teachers and ministers to those who did. And those were some of the things that my parents, my family did. My relatives had been storekeepers and ministers and teachers, but for the most part, these were -- this was a constricted world to which you were really condemned at that era -- in that era.

REHMWhere did you live here in Washington?

WILKERSONPetworth.

REHMIn that Petworth area.

WILKERSONYeah.

REHMTell me the street.

WILKERSONOh, my goodness. I lived at -- I lived near -- do you know where I lived? I lived near Soldiers' Home, which is where the emancipation proclamation was written by Abraham Lincoln, President Lincoln. That's where I lived. I lived right in that area.

REHMYou were inspired, absolutely.

WILKERSONYes.

REHMAnd I lived on Taylor Street here in Washington. And when these blacks then moved north, what kinds of jobs could they get?

WILKERSONThere were still restrictions because the North was not always as welcoming as they had hoped and dreamed that it would be. And so many of them, though, of course here in Washington, were able to get jobs in the government. They were able to work often entry-level positions, but they were able to get work that they could not -- work that was inside, work that meant they got a paycheck, as opposed to whatever was decided to be handed to them at the end of the week, a dollar a day or something for the work that they might do in the field.

WILKERSONMany of the people throughout the rest of the country ended up working in the factories and the foundries and the steel mills in the North. And this was a way, really, for the entire history of African-Americans in this country -- this was the first time that they were actually able to get paid, actually, truly get paid for their hard labor.

REHMAll right. We've got some other callers. Let's go to Lee, in Tallahassee, Fla. You're on the air.

LEEI can't believe it. I guess I'm gonna be the exception to the rule. My dad was from rural north Florida, a place called Quincy, Fla., near Tallahassee. And I grew up in the South and it was racist, but it wasn't in my home. My grandmother, her house -- she had a house -- a cook that worked there and he was part of our family. And his family was considered part of my family. So when they would need me to be taken care of, they'd take me out to his house. And I grew up, you know, with a different outlook.

LEEYou know, I was telling the interviewer I can remember when I was probably 12 years old and our housekeeper brought her son to help us clean the windows of the house. And after we cleaned the windows, my brother and this fellow, we were playing football in the front yard. And later I heard individuals asking my parents what was I doing playing football with a black boy in my front yard. And I'm going, it's a game, you know. But, you know, I -- it was just different in my house.

REHMInteresting, Charles.

DEWI think you were lucky. I think you had parents who probably were exceptions in your community. I've been to Quincy, Fla. I was there when school integration was just taking place. I saw some of the worst poverty I've ever seen in my life in the fields around Quincy, where they were growing shade-grown tobacco, where families, African-American families were living in what had clearly been slave quarters. Your experience was exceptional, I would say. And I would say you were lucky. I wish it had been replicated many, many times over.

REHMAnd to Susan, in Roxobel, N.C. You're on the air.

SUSANThank you for taking my call.

REHMSurely.

SUSANI just want to relate an experience that I had in the early '50s. I'm a 68-year-old white woman who was raised mostly in California, but went to Mississippi every summer to visit my grandfather. And when I was in a department store with my mother there were two water faucets. And one said white and one said colored. Being a seven-year-old, I ran over to the colored, thinking it meant colored water.

SUSANBut my mother, of course, right away, you know, grabbed me back and said, Susan, you know, don't use that faucet, that's for the black people. And I mean, I just -- I had this in my mind ever since then that how horrible that was. And I mean I never experienced that in my home in California. And my parents were not like, you know, were not racist like that at all.

WILKERSONThat's something that actually I hear quite a bit because it speaks to the joyfulness of children who do not come into this world hating.

DEWCorrect.

WILKERSONIt has to be taught to people. It has to be drilled in. You can see the level of effort that the parent is having to make to drag the child away from where the child wants to go, because the child doesn't know.

REHMOf course.

WILKERSONWe come into the world blank slates, just wanting to love everybody. And then we have to be taught to hate.

REHMHere's an email from Sergio in Bethesda, Md., who says, "Your guests are furthering the education we need in our country. I would like to ask them if they think a reconciliation commission on race relations in our country would be possible and effective in educating our citizens on the history and continuing effects of discrimination in our country. There are too many people who have no idea the extent of the continuing effects of slavery, Jim Crow laws and discrimination against blacks."

WILKERSONI couldn't agree more. You know, after the Charleston massacre a year ago, the Commonwealth of Virginia, the Richmond Times Dispatch made the courageous, I believe, and timely editorial they wrote, calling for a truth and reconciliation commission and calling for it to come out of Richmond, to come out of the Commonwealth of Virginia because that had been the capital of the confederacy. And I would -- I think it's so urgent for our country, particularly as things grow more divisive and there seems to be more polarization, that there needs to be this urgent need for us to know how we got to where we are. Most people have no idea.

REHMExactly. Charles Dew?

DEWI couldn't agree more. A truth and reconciliation commission would be a vital thing for us as a country to undergo. We need to clean up the myths about history. We need to clean up the myths about slavery. We need to clean up the myths about white supremacy, what caused the Civil War. Historical memory is very important. It can affect what happens today. It can affect policy. A truth and reconciliation commission would be a national blessing, I think.

REHMIs there, in your mind, still a need for reparation, as well as reconciliation?

DEWI see reparations as coming in the form of equal education, better jobs. I think a commitment to recognize the depravation that African-Americans have suffered should prompt us to be genuine about where we put resources in modern America. It would be very difficult to make individual reparations. The legal system doesn't really accommodate that sort of thing. You'd have to show injury. You'd have to have standing before the court. I think as a country, we should represent ourselves as being just and generous by committing resources, significant resources.

WILKERSONI think that much of the time when we speak about reparations, people are thinking about the time of enslavement. I think that what's coming out, as we have a clearer view of what's happened in our country in the 20th century, I think that clearly there has been a tremendous injury to people who are alive today. All of the people who survived Jim Crow, all of the people who survived the restrictions on their ability to go to the state schools if they wanted to go to college.

WILKERSONMy mother could not go to any public college in the state of Georgia because African-Americans were not permitted to do so. My mother is still alive. When she sought to buy a home here in Washington, D.C., there was red-lining and there were restrictive covenants. There was -- the Federal Housing Authority did not provide or allow mortgages to be granted to African-Americans. There was actual injury to many millions of Americans alive today.

REHMAnd you're listening to "The Diane Rehm Show." People have forgotten that.

WILKERSONPeople have forgotten. In some ways, they never knew on some level. Because if it doesn't touch you and your family, you just -- you would not be aware of the damage being done to people right before your eyes. I wanted to share one story out of this book. And that was that there was a physician who was forced to leave Louisiana because he couldn't -- he wasn't permitted to practice surgery in Monroe, La. This is in the 1950s, 1953.

WILKERSONHe sets out -- he begins to set out for California, but he stops by a storekeeper, a white storekeeper whom his family has had a close relationship with, have enjoyed work with, a tailor. And he tells the tailor, I'm getting ready to leave. I'm heading to California. He said, well, why are you going? He said, well, they -- I can't practice surgery here in Monroe, La. And he said, well, why can't you work at St. Francis? Why do you have to go out to California?

WILKERSONHe said, they don't permit African-American doctors to work at St. Francis. And this man did not realize. He had grown up…

REHMLiving right there.

WILKERSONLiving right in that town.

REHMHe did not know.

WILKERSONAnd so what I say in there is that how is it that people can see someone in a cage, but not see the bars.

REHMAnd I can recall going to the National Theater here one time with my mother and not knowing that blacks were in the balcony. Not knowing that they could not be seated with us. That's how ignorant I was as a child. So I think you're absolutely right. People do not know. And, Charles Dew, it's up to books like yours and, Isabel Wilkerson, books like yours to help educate people so we begin to understand these reports coming from the Department of Justice. What do you think may come from a report like that, Charles Dew?

DEWI live in hope. I like to be an optimist. I think we're a decent country, a decent people. I think if we can become aware of these things, we can deal with them. That's why it's so important to confront them honestly and openly. We were talking about historical myth. We have to deal with a lot of the same sort of a thing in present day America. There is just so much misunderstanding and so much ignorance. And those are barriers we should be able to do something about.

REHMIsabel, do you think this report from DOJ is going to create change?

WILKERSONI think that change comes incrementally. I think change comes with -- from many different sources. There's no one thing that creates change. I think it involves all of us. I think looking to one document, looking to one moment is not sufficient to make the change that we need to in our country. I think all of us need to search our souls. All of us need to open our eyes and recognize what's going on around us. This is not the time to be living in denial and living in ignorance any further because it's out there for all of us to see. And I think we all have a place in finding the answer.

REHMIsabel Wilkerson, she's a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. She won the National Book Award for her 2010 book, "The Warmth of Other Suns." Charles Dew is professor of American history at Williams College. His brand new book is titled, "The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History and Slave Trade." Thank you both so much for being here and for sharing your stories.

DEWThank you, Diane.

WILKERSONThank you. Great to be here.

REHMAnd thanks all for listening. I'm Diane Rehm.

After 52 years at WAMU, Diane Rehm says goodbye.

Diane takes the mic one last time at WAMU. She talks to Susan Page of USA Today about Trump’s first hundred days – and what they say about the next hundred.

Maryland Congressman Jamie Raskin was first elected to the House in 2016, just as Donald Trump ascended to the presidency for the first time. Since then, few Democrats have worked as…

Can the courts act as a check on the Trump administration’s power? CNN chief Supreme Court analyst Joan Biskupic on how the clash over deportations is testing the judiciary.